Two of the wealthiest families in American history built mansions to rival palaces and chateaus in Europe. It practically became a sport among them to see who could outdo one another. It got so out of hand some heirs blew their entire fortune on these houses. It’s insane to us regular folk but remember, many heirs never managed money; they just spent it. They always had unlimited money, or so it seemed and so they lived and built homes as if it were unlimited… until it was not. Regardless, America is peppered with many stunning homes to which the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers contributed greatly.

Let’s Kick Off the Vanderbilt vs. Rockefeller Mansion Showdown in Hudson Valley, New York

In the battle of Hudson Valley mansions, it’s hard to decide whether the Vanderbilts or the Rockefellers took the prize for grandiosity — both families made sure their estates screamed wealth and power. The Vanderbilts, with their Gilded Age extravagance, gave us the Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park. It’s a 54-room Beaux-Arts palace perched on 600 acres of manicured lawns. If your idea of “country living” involves marble fireplaces, European antiques, and an attention to symmetry that borders on obsessive, the Vanderbilts have you covered. Meanwhile, the Rockefellers’ Kykuit in Pocantico Hills plays the long game. Built in a more restrained classical revival style, Kykuit is less about showing off and more about an understated blend of art, architecture, and philanthropy. Sure, there are 40 rooms, but what really sets Kykuit apart are the extensive art collections, the perfectly sculpted gardens, and the sense that the place is curated, not flaunted.

Vanderbilt Mansion at Hyde Park

The Vanderbilt Mansion in Hyde Park is what happens when American tycoons decide that European aristocrats haven’t been showing off nearly enough. Designed by McKim, Mead & White, this Beaux-Arts extravaganza is the architectural equivalent of a money-fueled mic drop. It’s a 54-room palace that doesn’t whisper wealth — it shouts it from the marble cornices and intricate wrought iron gates. Walk through the front doors and you’re greeted by ceilings that could have been plucked from a Renaissance palace, and furnishings that seem to have come straight from Louis XIV’s “spare” collection. Outside, the perfectly symmetrical terraces lead your eye to the Hudson River, as if the landscape itself were another ornament. This wasn’t just a house—it was a statement. The Vanderbilts built Hyde Park to show the world that the American dream wasn’t just alive — it was gilded, marble-clad, and sitting on 600 acres of manicured land. If you ever wanted to know what it felt like to be on top of the world, Vanderbilt Mansion is a good place to start.

Rockefeller’s Kykuit at Pocantico Hills

Kykuit is the Rockefeller answer to the Gilded Age mansion — but in typical Rockefeller fashion, it’s less gaudy showmanship and more restrained elegance. Sure, it’s 40 rooms, but the house isn’t trying to knock you over the head with its wealth. Built in the neoclassical style, Kykuit avoids the Beaux-Arts opulence of the Vanderbilts in favor of subtle lines, perfectly sculpted gardens, and an art collection that casually includes works by Picasso and Warhol. The real star of the show, though, is the view: sweeping Hudson River vistas framed by rolling hills and manicured grounds that make you feel like you’ve stepped into a Rockefeller version of Eden. And then there’s the basement, which holds an antique car collection. Kykuit’s significance lies in its balance of wealth and taste. It’s not about flaunting the cash, it’s about curating culture and living the good life without feeling the need to scream it from the rooftop. If the Vanderbilts were the showboats of their time, the Rockefellers were the patrons of understated power. So who wins? If you’re after sheer opulence, Vanderbilt’s Hyde Park estate takes it. But if you prefer a blend of cultural legacy with a little less pomp, Kykuit, with its subtle grace and Rockefeller restraint, claims the crown. In the end, it’s a question of taste — exuberant opulence or cultured refinement? Either way, you’re walking into history.

Newport, Rhode Island – Where the Mansion Building Frenzy Went Bananas

When it comes to Newport, Rhode Island, the Vanderbilts didn’t just build homes; they built statements. The Breakers is the crown jewel, an Italian Renaissance-palazzo-on-steroids, dripping with marble, gilded ceilings, and enough opulence to make Versailles blush. Cornelius Vanderbilt II wasn’t going for subtle. Walking through The Breakers feels like being swallowed whole by wealth, every room designed to awe and overwhelm. Then there’s Marble House, another Vanderbilt masterpiece, a Beaux-Arts extravaganza created by Alva Vanderbilt that’s less a home and more a lavish love letter to Louis XIV.

The Breakers – A Vanderbilt Masterpiece that Reigns Supreme

The Breakers, designed by Richard Morris Hunt in the late 19th century, is a monument to the Gilded Age, a time when American aristocracy built with the sole purpose of one-upping each other. This 70-room mansion, set on 13 acres of prime Newport real estate, is a masterpiece of Italian Renaissance architecture. Every inch of the building oozes luxury: imported marble, rare woods, and a ceiling fresco in the great hall that could give Michelangelo a run for his money. The Breakers wasn’t just a home, it was Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s way of announcing that his family was at the top of the social heap. Designed with every conceivable luxury in mind, from the state-of-the-art plumbing (for its time) to an opulent grand staircase, The Breakers remains one of the most iconic examples of Gilded Age excess.

Marble House – Also an Architectural Masterpiece

Marble House is a grandiose ode to European royalty, thanks to Alva Vanderbilt’s obsession with French court life. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, Marble House is Beaux-Arts architecture at its finest, with an estimated 500,000 cubic feet of marble brought in to create the mansion’s lavish interiors. Think gilded moldings, intricate carvings, and a ballroom that could host a Louis XIV-worthy soiree. Built between 1888 and 1892, this mansion set the standard for Newport’s elite, becoming a turning point in America’s architectural history. Alva’s goal was to create a social hub, and she succeeded — this was where Newport’s high society mingled. Every room was designed with grandeur in mind, from the opulent dining room to the Gold Room, and even the exterior’s classic columns give the place a sense of timeless elegance. Marble House still stands as a symbol of unapologetic luxury. In terms of architectural bravado? The winner is clearly the Vanderbilts. The Rockefellers may have defined wealth in more practical ways, but in Newport, where showmanship counts, the Vanderbilts reign supreme. In the end, it’s a question of taste — exuberant opulence or cultured refinement? Either way, you’re walking into history.

Taking the Mansion Showdown Way on Down to Florida

When it comes to Florida, the Rockefeller-Vanderbilt mansion showdown is more of a one-sided affair. On one hand, you have The Casements, John D. Rockefeller’s relatively understated winter retreat in Ormond Beach. Built in 1913, this Mediterranean Revival-style mansion became Rockefeller’s winter home in 1918. While charming, it lacks the over-the-top grandeur you’d expect from the richest man in the world. Think of it as Rockefeller on vacation mode — restrained, sunny, but not about to show off. You won’t find endless ballrooms or glitzy salons here. It’s all about comfort, health, and escaping the cold New York winters. On the other hand, the Vanderbilts left a much smaller footprint in Florida, with no grand mansions to speak of in the Sunshine State. Their architectural legacy is mainly tied to their Gilded Age palaces up north, like The Breakers in Newport or the Biltmore in North Carolina. In Florida, they simply didn’t go all – in the way the Rockefellers did, leaving this round to the oil baron.

Rockefeller’s The Casements

While not the largest or most opulent, The Casements stands out for its architectural charm and historical weight. The Mediterranean Revival style, with its stucco walls, red-tiled roof, and arched windows, made it a perfect fit for Florida’s subtropical climate. What makes it significant isn’t its grandeur but the fact that it reflects Rockefeller’s late-in-life shift toward simplicity and retreat. It was designed for relaxation, not spectacle — a far cry from the oil magnate’s more ostentatious properties. The Casements captures Rockefeller’s personal desire for comfort and quiet, wrapped in Florida’s sunshine. Plus, with its role as a cultural hub today, it’s not just a relic but a living piece of history. Winner: Rockefellers. Though understated, The Casements holds its own by simply existing, while the Vanderbilts chose to focus their grandeur elsewhere.

Mansion Showdown in the South

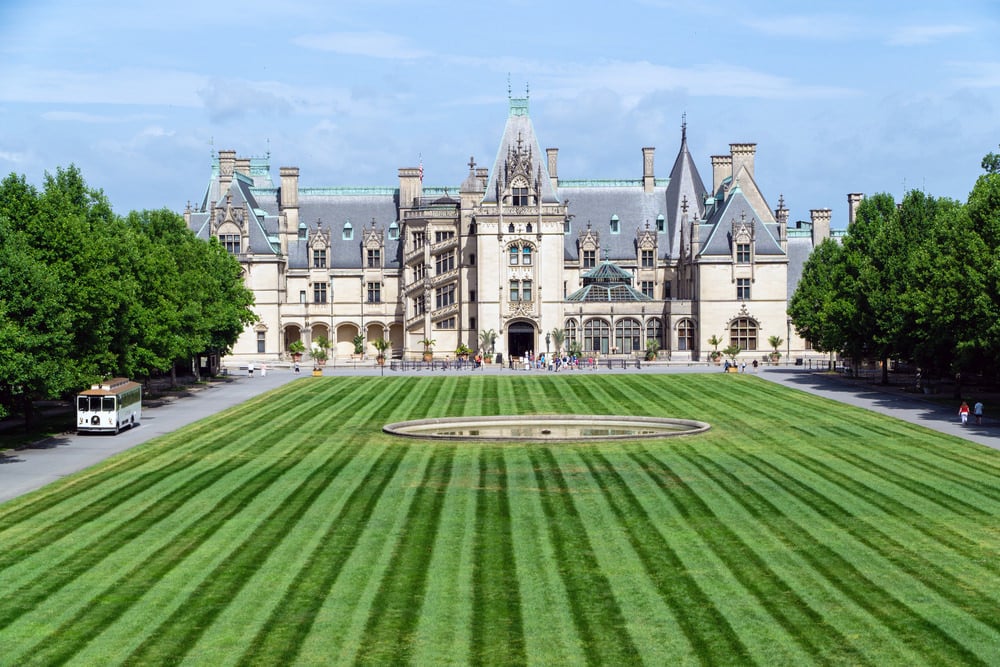

When it comes to grand mansions in the South the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers took different approaches. The Vanderbilts blew the roof off the Southern real estate game with Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina — a sprawling 250-room French Renaissance chateau that’s more Versailles than vacation home. Built by George Washington Vanderbilt II in 1895, Biltmore flaunts everything from a 10,000-volume library to a banquet hall with a seven-story high ceiling. It’s the largest privately-owned home in the U.S. and feels like the kind of place Louis XIV would’ve been jealous of. It’s opulence on steroids, complete with a winery and vast gardens designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. The Rockefellers, on the other hand, went a little more subtle with their southern statement. Reynolda House in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, built by R.J. Reynolds’ daughter, Mary Reynolds Babcock, who married into the Rockefeller family, blends Southern gentility with early 20th-century style. It’s an American Country House with a mix of Colonial Revival and Arts and Crafts architectural vibes. The estate includes gardens, art galleries, and some genuine Gilded Age splendor, but let’s be honest, it’s no Biltmore.

Vanderbilt’s Biltmore Estate

Biltmore’s architectural significance is hard to overstate. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, it represents the pinnacle of American opulence in the Gilded Age. Its French Renaissance architecture, with steeply pitched roofs, turrets, and limestone facades, echoes the grandeur of European castles. Inside, no detail is too small or too extravagant — from its library to the indoor swimming pool and bowling alley. The vast surrounding gardens, designed by Central Park’s Frederick Law Olmsted, complete this estate’s embodiment of wealth and culture. Biltmore is less a mansion and more a self-contained universe of luxury, making it a true Southern icon. Hurricane Helene, a fierce Category 4 storm that swept through the Southeast in September 2024, caused significant damage to the Biltmore Estate, including its grand entrance and surrounding farm areas. The nation’s largest privately owned home temporarily closed its doors for necessary repairs.

Rockefeller’s Reynolda House

Reynolda House, sitting quietly in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is no Biltmore, but it has its own brand of understated elegance that deserves attention. Built in 1917 by Katharine Reynolds, wife of tobacco magnate R.J. Reynolds, this house is a genteel nod to both Colonial Revival and the Arts and Crafts movement. It’s not trying to flex its architectural muscles with turrets or grandiose ballrooms, but there’s an inherent charm in its simplicity. You step inside, and it’s like you’ve walked into an old money Southern dream. There’s a symmetry and quiet dignity to the design, with wide verandas and ample natural light. Winner: The Vanderbilts take this one. Biltmore’s staggering size, artistic ambition, and sheer luxury easily outshine the Rockefeller’s Southern efforts.

Rockefeller and Vanderbilt Legacies in New York City

When it comes to building grand mansions in New York City, the Vanderbilts and Rockefellers were like two heavyweight champs slugging it out in the architectural ring. The Vanderbilts came out swinging with their colossal Fifth Avenue homes, like the 1882 “Triple Palace” designed by Richard Morris Hunt, which took up an entire city block between 51st and 52nd Streets. The idea was to scream old-world wealth with Beaux-Arts flourishes and enough opulent details to make European royalty feel underdressed. Hunt’s design gave New York City one of its most lavish architectural statements, complete with towering columns, marble galore, and enough gilt to make Versailles blush. These homes were less mansions and more urban castles, exuding wealth like a diamond-studded scepter.

Grand Central Terminal – Vanderbilt

The Vanderbilts left an architectural footprint in New York City that goes far beyond their opulent mansions. Take Grand Central Terminal, for example — a monument to ambition, extravagance, and sheer practicality. This isn’t your average commuter hub. The celestial ceiling alone is worth a visit, with constellations so dazzling they almost make you forget you’re running late for a train. It was Cornelius Vanderbilt who first envisioned a New York transport empire, and what began as railroads morphed into a city-shaping legacy. Then there’s the Vanderbilt Gate at Central Park, standing like a refined yet imposing doorman to the city’s favorite backyard. These structures don’t scream old money, they casually mention it—letting you know that the Vanderbilts not only had wealth but knew how to flex it with style. They shaped New York’s skyline, not just with excess but with enduring functionality that still breathes today.

The Vanderbilt Mansions

The Vanderbilts spared no expense in turning New York into their personal palace playground. The “Triple Palace” on Fifth Avenue was a Beaux-Arts dream, designed to make every passerby feel like a peasant. Architect Richard Morris Hunt drew from French and Italian influences, layering in Corinthian columns, ornamental façades, and marble-lined staircases that spiraled like architectural winks at the Louvre. The interiors, stuffed with imported European art and enough gold leaf to blind a Renaissance pope, stood as tributes to an old-money world transplanted into the hustle of Manhattan. Even if the Vanderbilts’ Fifth Avenue legacy has mostly disappeared, the grandeur of these buildings still echoes through New York’s architectural lineage. Then there are the Rockefellers, who went with a different kind of grand. Their focus wasn’t just on a private residence — they put their stamp on the city itself with Rockefeller Center. The understated mansion at 10 West 54th Street may not have been as flashy, but Rockefeller Center? That was a game changer. A sleek Art Deco masterpiece, this wasn’t about ostentatious wealth — it was about shaping the skyline. The Rockefellers built a new kind of grand: a modern architectural legacy wrapped in sleek, geometrical forms.

The Rockefeller Legacy – Rockefeller Center

While the Vanderbilts were building mansions, the Rockefellers were busy reshaping the city itself. Their 10 West 54th Street residence might seem modest by comparison, but Rockefeller Center is where they flexed real muscle. Designed by Raymond Hood and others, the 19-building complex is a marvel of Art Deco geometry. The vertical lines and polished limestone façades whisper sophistication while screaming modernity. Instead of hiding behind wrought-iron gates, the Rockefellers’ creation reached skyward and outwards, transforming Midtown into a hub of culture, business, and style. With its clean lines and towering heights, Rockefeller Center remains an enduring symbol of 20th-century ambition. Winner? Rockefeller Center takes the belt, shifting the focus from personal palaces to city-defining landmarks. The Vanderbilts had flair, but the Rockefellers played for keeps, leaving an indelible mark on the heart of Manhattan. In the showdown for New York City’s grandest architectural legacy, the Rockefellers stand undefeated.

Direct Rivalry? Not really.

The two families were more focused on their own empires rather than direct competition. The Vanderbilts were already an established dynasty when the Rockefellers were rising in the late 19th century. By the time John D. Rockefeller became the world’s richest man, the Vanderbilt empire had started to decline somewhat, partly due to the extravagant spending of subsequent generations. In the Gilded Age social circles, they may have vied for prominence and prestige, but they weren’t business rivals in the way we see corporate competition today. In the end, the Rockefellers arguably had the last laugh — while the Vanderbilts spent much of their fortune on mansions and a lavish lifestyle, John D. Rockefeller became the world’s richest man.