Between 2018 and 2023, Colorado’s housing market flipped more than once. The pandemic drove buyers into the mountains and onto the plains, chasing space, quiet, and affordability. Urban hubs like Denver and Colorado Springs saw fierce demand early on, but by 2022, the frenzy had cooled. Meanwhile, rural regions—from the Western Slope to the San Luis Valley—gained new attention from buyers who once wouldn’t have looked twice. This urban-rural divide isn’t just about location—it’s about lifestyle, priorities, and the way Coloradans rethink home in a changing world.

Statewide Market Overview (2018–2023)

The Boom Years (2018-2021)

From 2018 to 2021, Colorado home prices and sales surged. Low interest rates (near 3% in 2020–2021) significantly increased buyer purchasing power.

Median sale prices roughly doubled over the 2010s, climbing from the mid-$300,000s in 2018–2019 to over $500,000 by 2021. Home sales reached record highs in 2020, with Denver-area sales 24% higher in 2020 compared to 2019.

Mountain resort counties experienced even more dramatic growth. Pitkin County (Aspen) home sales jumped 458% in September 2020 compared to the previous year. This rush was fueled by remote work opportunities and buyers seeking more space during COVID-19.

The Cooling Period (2022-2023)

By late 2022 into 2023, the market cooled as interest rates rose toward 6–7%. Statewide median prices leveled off around $530,000 by end of 2022 (barely up 0.5% from 2021), and sales slowed considerably. Inventory of homes for sale began to recover from record lows.

In summary, 2018–2021 represented an extremely competitive seller’s market, while 2022–2023 shifted toward a more balanced market with significantly slower price growth.

Urban Areas: Front Range Cities

Denver Metro Area

The Front Range urban corridor led Colorado’s housing frenzy. Denver and its suburbs experienced sharp price increases and critically low supply. From 2013 to 2023, the average Denver County home price soared about 138% (from approximately $235K to $560K).

By early 2022, finding any single-family home under $400,000 in the Denver area was nearly impossible. At the height of demand in 2020–2021, Denver had only 2–3 weeks of housing supply – an all-time low inventory. In December 2020, active listings in Denver metro were down 68% from the previous year, leaving just a 0.5 month supply of single-family homes available.

Homes often sold within days, frequently above asking price due to intense bidding wars. This began easing by late 2022, with Denver’s median days on market stretching from under 1 week during peak demand to about 2 months by 2023. Price growth also moderated significantly. Denver’s median price in early 2024 increased only 0.8% year-over-year (around $625,000 in the metro) – essentially flat after several years of dramatic gains.

Condo sales in the city increased as an affordable alternative. Downtown Denver saw new condo developments with younger buyers opting for condos (often in the $300K+ range) when single-family homes were unattainable.

Colorado Springs

Colorado’s second-largest city experienced similar trends. Home prices in Colorado Springs (El Paso County) rose approximately 119% from 2013 to 2023. By 2021–2022, Springs properties commonly sold in competitive bidding situations, with median prices reaching the mid-$400Ks.

Colorado Springs benefited from Denver workers relocating there for more affordable housing – the average home price ($445K in 2023) remained lower than Denver’s ~$560K. This attracted buyers seeking more house for the money while accepting longer commutes.

Other Front Range Cities

Other Front Range cities like Fort Collins, Greeley, and Boulder also saw high demand. Boulder remained the most expensive market in the state (median often $800K+), effectively pricing out many middle-income buyers.

By 2023, urban markets finally experienced a reprieve: inventory improved and buyers gained slightly more negotiating power than during the 2020–2021 frenzy. Nevertheless, urban Colorado throughout 2018–2023 largely remained a seller’s market with rapid sales and high prices compared to the previous decade.

Rural & Mountain Areas

Western Slope Communities

Grand Junction/Mesa County: Long one of Colorado’s most affordable areas, Mesa County’s median home price was around $218K in 2017. Increasing demand from retirees, remote workers, and Front Range emigrants pushed Grand Junction’s median into the mid-$300Ks by 2023.

From 2013 to 2023, home prices in Mesa County more than doubled (+113%). Even with this growth, Grand Junction remained relatively affordable by Colorado standards, attracting budget-conscious buyers.

Pueblo in southern Colorado maintained the lowest prices in the state (~$287K average in 2023) and saw increased interest from Denver/Springs buyers seeking cheaper housing. Pueblo’s prices roughly doubled between 2013–2023, yet it remained one of the few places where homes under $300K were still available.

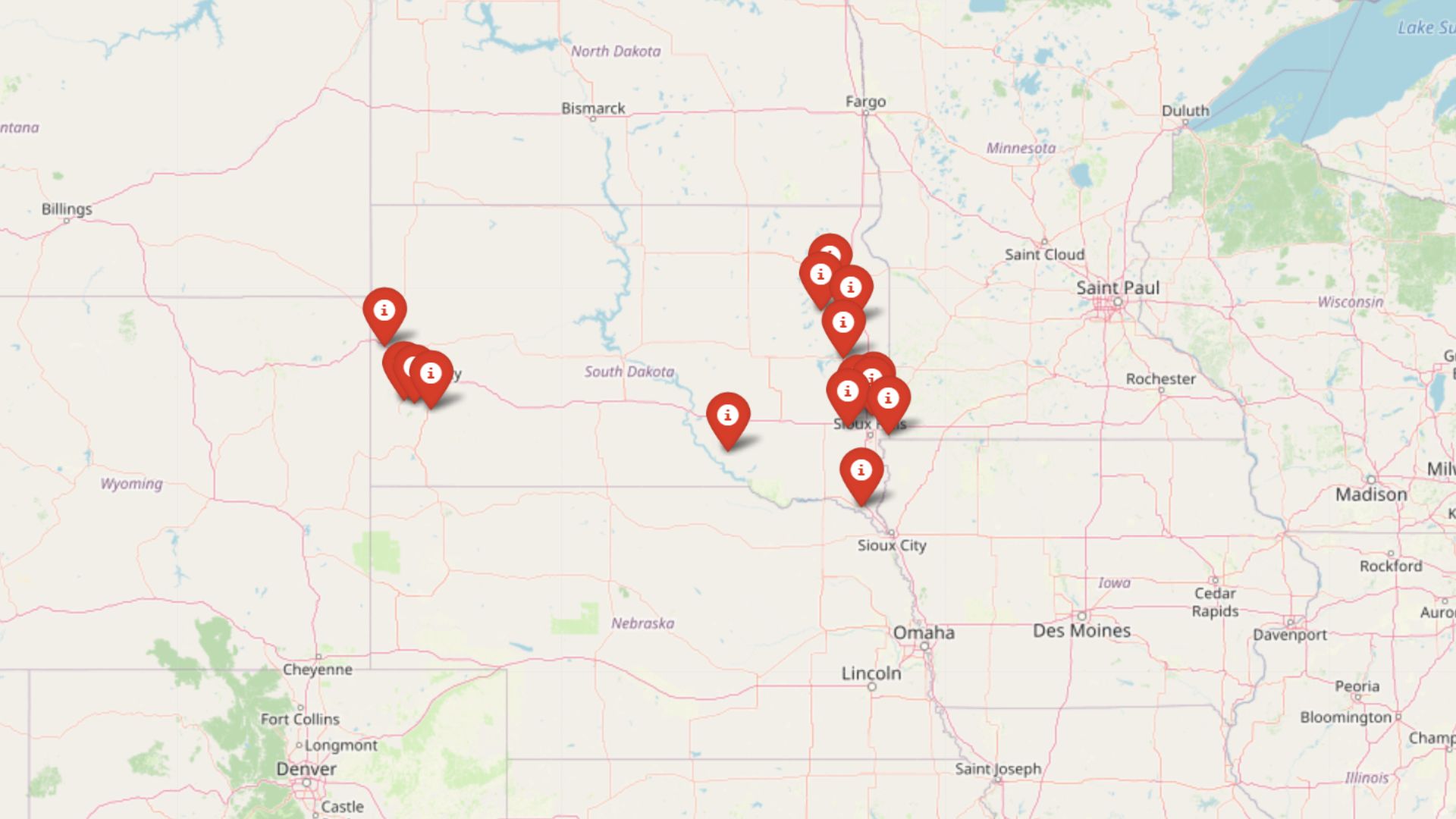

Eastern Plains & San Luis Valley

These agricultural regions and small towns experienced slower growth with relatively low prices but thin demand. Counties on the far Eastern Plains (around Sterling or La Junta) didn’t experience the dramatic price fluctuations seen in Denver – their markets stayed modest and relatively stable.

However, 2020–2021 brought a surprising uptick in some rural populations. Places like the San Luis Valley and Eastern Plains, which had been losing population for years as younger residents departed, saw slight population gains (e.g., +0.4% on the Eastern Plains) as some urbanites moved in with remote jobs and older adults left cities.

State demographers noted this “telework” migration helped offset natural population declines in rural counties. Remote work enabled a trickle of new homebuyers into rural Colorado who previously wouldn’t have considered living there.

Despite this modest influx, rural eastern Colorado continues to be characterized by slower market activity with predominantly local buyers. Many homes are older and lower-cost, with fewer lenders and programs available, creating purchase challenges despite the lower prices.

Mountain Resort Communities

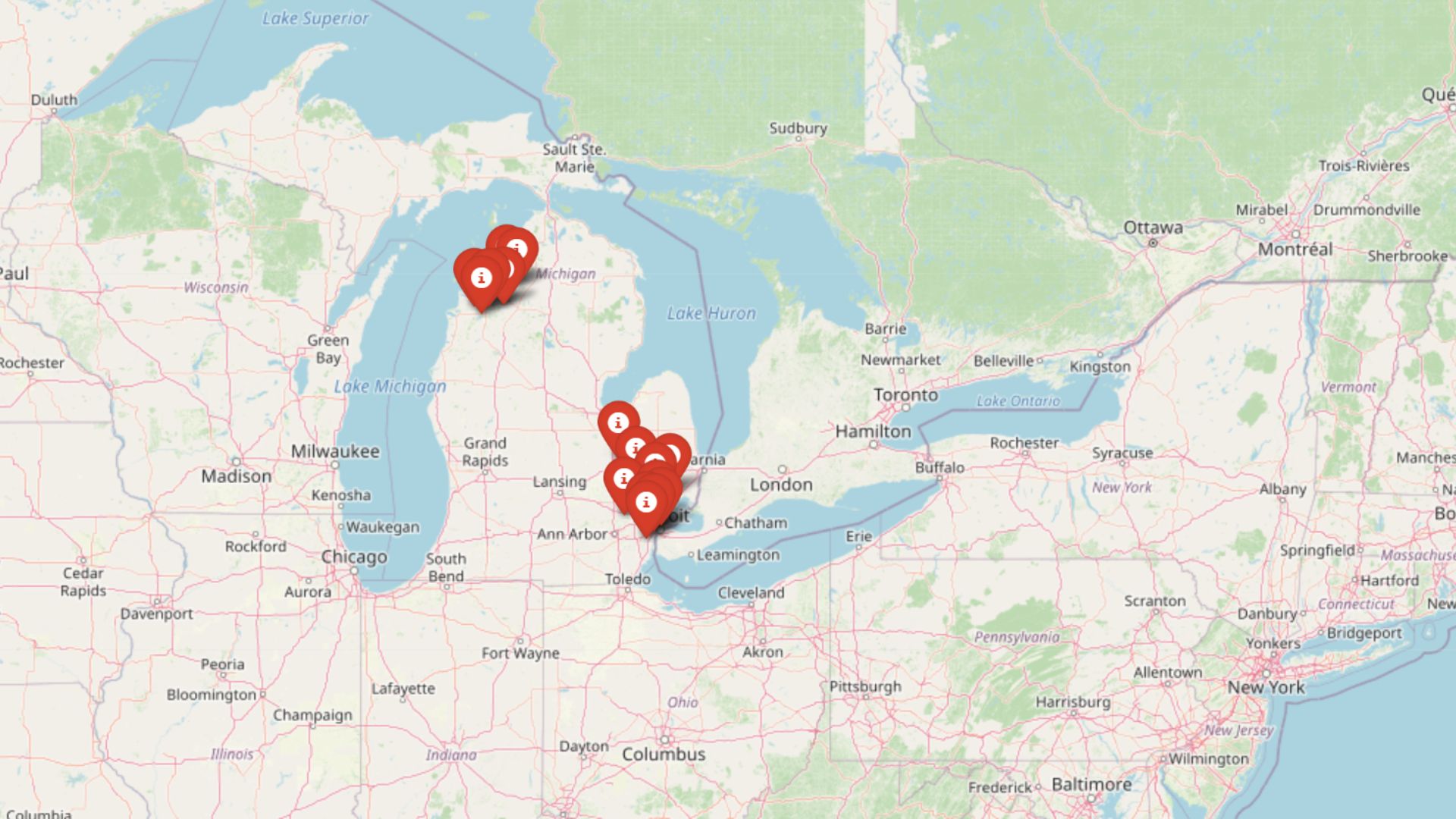

Colorado’s high-country resort towns (Aspen, Vail, Summit County, Telluride) experienced an unprecedented buying spree in 2020–2021. After initial pandemic lockdowns, wealthy urban buyers from Denver and out-of-state flooded into mountain areas.

By fall 2020, real estate sales in resort counties shattered records:

- Pitkin County (Aspen): September 2020 sales volume up 458% vs. September 2019

- Eagle County (Vail): Up 230% year-over-year

- Routt (Steamboat) and San Miguel (Telluride) counties: Sales more than doubled

These buyers were primarily remote workers or second-home seekers looking to escape urban environments. Many came from Denver, Texas, California, and Florida, seeking larger homes with dedicated office spaces and room for extended family.

By 2020, Aspen had its largest real estate year ever – Pitkin County was tracking toward nearly $3 billion in sales, far exceeding any previous year. In Summit County (Breckenridge area), more than half of all housing units were classified as vacant in the 2020 Census. This “vacant” designation is misleading – up to 71% of homes in some ski counties were actually second homes or vacation rentals rather than truly unoccupied.

The mountain boom further tightened local housing for workers as demand from affluent buyers pushed prices beyond what local employees could afford. Many newcomers decided to convert their second homes into primary residences – moving in full-time and enrolling children in local schools, increasing year-round residency in resort communities.

After 2021, as travel resumed and offices reopened, the mountain frenzy moderated. By late 2022, sales volumes had normalized from their 2020 peak (though remained historically strong), while inventory in resort areas remained tight.

Land Sales

During the height of the housing shortage in 2020, many frustrated buyers turned to vacant land purchases. Statewide, land acquisitions skyrocketed as people planned to build homes instead of continuing unsuccessful searches for existing properties.

Finding contractors, however, proved equally challenging. This trend was particularly notable in mountain and rural counties where buildable land was available, reflecting the lengths buyers would go to secure property when home listings were scarce.

Changing Homebuyer Preferences

Upsizing Trends

A clear pattern in 2018–2023 was buyers seeking more space. With remote work becoming common and families spending increased time at home, many wanted larger houses with extra rooms for offices and bigger yards.

During the pandemic, urban professionals living in small city apartments or condos often “upsized” to larger homes in suburbs or mountain communities. Local real estate professionals described it as the “great COVID migration,” as people abandoned city living for spacious homes in quieter areas.

Millennials (late 20s to late 30s during this period) drove much of the upsizing trend as they transitioned from renting to homeownership. First-time buyers in 2018–2021 were often millennials finally entering the market, moving from apartments to starter homes.

Those with financial means in 2020–2021 frequently skipped the traditional “starter home” phase and purchased larger properties thanks to favorable interest rates. Additionally, some existing homeowners leveraged Colorado’s rising equity to “trade up” – selling smaller homes to buy larger ones when additional space was needed (though this became less common by 2022 as interest rates increased).

Downsizing Realities

While upsizing was prevalent, downsizing occurred more gradually than expected. Colorado has many Baby Boomer homeowners (ages mid-50s to 70s) who theoretically might sell large family homes for smaller residences. However, the anticipated “silver tsunami” of boomer sales did not fully materialize in the late 2010s.

Compared to 2008–2017, more boomers in 2018–2023 chose to age in place. Boomers are healthier and working longer than previous generations, with many feeling no urgency to relocate at retirement age if their current homes remained comfortable.

Downsizing in Colorado became less financially advantageous when even smaller condos or patio homes commanded high prices. Some boomers who wanted to downsize discovered that selling their large house and purchasing a smaller one in the same area produced minimal savings due to elevated prices across all property types.

As a result, many stayed in their existing homes, which actually contributed to the inventory shortage (fewer older homes coming on the market). A segment of boomers did downsize or relocate for retirement, with affluent retirees purchasing homes in scenic areas as retirement or second homes. Others moved into new senior-friendly developments in suburbs that offered reduced maintenance while remaining near family.

Second Homes and Vacation Properties

The second-home market flourished during this period. By 2018, Colorado’s resort counties already had a high proportion of second homes, which only increased during the pandemic.

Nationally, vacation home sales jumped 16.4% in 2020, significantly outpacing overall home sales growth. By early 2021, vacation/second-home purchases were up 57% year-over-year. Colorado exemplified this trend, with wealthy buyers acquiring mountain cabins, ski condos, and lake houses at unprecedented rates.

Many paid all cash – by 2021, 53% of U.S. vacation home buyers paid cash, with Colorado seeing similar figures in high-end markets. Popular second-home destinations included Vail, Aspen, Telluride, Breckenridge, and Steamboat Springs, along with smaller towns offering outdoor recreation.

In some counties (like Hinsdale County/Lake City), the 2020 Census found over 70% of housing units were second homes or seasonal rentals, highlighting the prevalence of non-primary residences.

The pandemic blurred distinctions between second and primary homes: some families who owned vacation properties moved into them full-time when offices closed. Others purchased second homes as both retreats and contingency plans against future lockdowns.

By 2022–2023, second home demand moderated as workplaces recalled employees and borrowing costs increased, but remained significant in Colorado’s market, especially in resort and scenic rural counties.

Demographic Influences

Age of Buyers

The typical Colorado homebuyer grew older during this period. Nationally, the median age of first-time buyers increased to 36 in 2022 (up from 32 in 2018), reaching approximately 38 by 2023. Colorado likely mirrored this aging trend.

Young adults postponed homeownership longer, often due to pricing challenges and debt burden. Most buyers in 2018–2021 were in their 30s (older millennials purchasing first homes). The proportion of very young buyers (20s) declined, while middle-aged and older buyers dominated the market.

Married couples remained the largest buyer segment (about 60–65%), but single women comprised a growing portion – around 20% of homebuyers by 2023. Single men represented roughly 8–10%, with unmarried couples at approximately 6%. This indicates evolving household compositions, with more individuals (especially women) purchasing independently.

Colorado also experienced growth in multigenerational households buying together. By 2022, 14–17% of U.S. home purchases were multigenerational (parents, adult children, grandparents sharing one home) – the highest proportion ever recorded. In Colorado’s expensive market, some families combined resources to purchase larger homes for communal living, an arrangement that gained popularity during the pandemic.

Income and Affordability

Colorado’s robust economy attracted numerous professionals, but housing costs outpaced income growth. Approximately 47% of Colorado households earn $75,000 or less (as of 2021), yet by 2023, a household earning the state median income (~$80K) could barely afford even a $300K home – a price point that had become scarce throughout much of the state.

This affordability gap skewed the buyer pool toward higher earners. Many successful buyers were dual-income couples in sectors like technology, healthcare, finance, or government/military (especially around Colorado Springs).

First-time buyers faced substantial obstacles. Traditionally representing about 40% of buyers, their share in Colorado dropped to ~34% in 2021 and fell to just 24% by 2023 – an all-time low. This means only about one in four buyers was a first-time purchaser, down from closer to one in three a decade earlier.

Younger and lower-income buyers were increasingly excluded by competition and rising interest rates. Those who succeeded often had above-average incomes or family assistance with down payments. Repeat buyers (with equity from existing homes) held a significant advantage.

Colorado’s homeownership rate did increase around 2020 when interest rates were low – rising to approximately 65.9% in 2021 (up from 62.4% in 2016) as many renters seized opportunities to purchase. By 2023, affordability challenges pushed ownership rates slightly lower again, with renting remaining common for those priced out of purchasing.

Remote Work Revolution

Remote work fundamentally transformed Colorado’s homebuying landscape. Before 2020, only a small percentage of Coloradans worked from home full-time. By 2021–2022, Colorado had one of the highest remote-work rates nationally.

Estimates indicate approximately 15–20% of Colorado’s workforce was working remotely (at least part-time) in 2021–22, the highest proportion of any state. This shift meant many professionals were no longer tied to offices in urban centers.

Workers could purchase homes anywhere in Colorado (or beyond) while maintaining their employment. This fueled migration patterns from urban centers to mountain towns, the Western Slope, and even rural plains areas, as professionals could work effectively from diverse locations.

Front Range professionals in technology and finance relocated to places like Summit County or smaller towns, generating localized real estate booms. Simultaneously, remote workers from other states moved to Colorado, bringing their coastal jobs while enjoying Colorado’s lifestyle advantages.

Remote work also altered home feature priorities: suddenly home offices and additional bedrooms became essential, as did reliable internet access in areas where connectivity hadn’t previously been emphasized. Even within cities, buyers sought more space to accommodate work-from-home requirements.

By 2023, some employers began recalling workers to offices, potentially slowing remote-work migration. However, many organizations maintained flexible policies, and Colorado’s high remote work ranking suggests this trend has permanently expanded housing options.

2018–2023 vs. 2008–2017: Key Differences

Market Cycle Contrasts

The 2008–2011 period brought recession and housing market decline to Colorado, with falling prices and numerous foreclosures. In stark contrast, 2018–2021 represented boom years with record-high prices and sales. The late 2010s featured a strong economy and population growth, driving demand upward.

By 2022–2023, Colorado faced a different scenario: not a crash but a gradual cooldown from peak levels due to interest rate increases – a more measured transition than the sharp 2008 downturn.

Price Growth Acceleration

The pace of price increase accelerated significantly in 2018–2023. Denver’s home prices rose approximately 138% over 10 years, with much of that growth concentrated in the latter half of the 2010s.

In 2008–2017, considerable time was spent recovering from the housing crash, resulting in slower overall price growth (with most gains occurring after 2012). By the early 2020s, Colorado prices reached unprecedented levels, whereas in 2008 many areas remained well below previous peaks.

Changing Buyer Demographics

The buyer composition shifted older and more affluent. In the late 2000s, Generation X dominated prime homebuying years with many first-time purchasers in their 20s. By 2018–2023, millennials (born ~1981–1996) became the primary first-time buyer cohort, entering the market later than previous generations.

The median first-buyer age increased to the mid-30s by 2023, compared to around 30 a decade earlier. Additionally, fewer first-time buyers could enter the market at all (only 24% of buyers in 2023 were first-timers, versus ~40% historically).

Baby boomers in 2008–2017 began retiring, with some selling homes to downsize or relocate to warmer states. In 2018–2023, more boomers opted to remain in place or even move into Colorado to retire near family, reducing the number of larger homes returning to the market and contributing to sustained inventory constraints.

Migration Pattern Shifts

From 2008–2017, Colorado experienced substantial in-migration – particularly during 2010–2015 when Colorado ranked among the fastest-growing states. Front Range technology and energy sector growth attracted numerous newcomers.

In 2018–2023, this trend began reversing. Migration slowed considerably, and by 2022 Colorado had net outbound migration (more departures than arrivals). Contributing factors included prohibitive housing costs and remote workers relocating to more affordable regions.

As a result, Colorado’s population growth rate, which peaked in the early 2010s, declined to approximately 0.5% by 2021. Internally, the pandemic triggered unusual micro-movements (urban to rural, as discussed). Overall, the state’s reputation as a population magnet diminished compared to the previous decade’s robust growth.

Interest Rates and Financing Evolution

The 2008–2017 period saw mortgage rates primarily between ~3.5–5%, with temporarily tightened lending standards following the mortgage crisis. In 2018–2023, buyers experienced extremes: rates around 2.7% at the 2021 low significantly enhancing affordability, then climbing to 6–7% by 2023, dramatically reducing purchasing power.

Financing methods also evolved – after 2010, fixed-rate mortgages and stringent underwriting became standard practice. By 2020, most buyers used conventional loans with substantial down payments or government-backed loans for first-time purchases, while cash offers grew increasingly common in competitive situations.

The prevalence of cash transactions or large down payments increased substantially in 2018–2023 due to fierce competition (notably, a majority of vacation home buyers paid cash by 2021). This contrasted sharply with mid-2000s practices when leverage was readily available and zero-down financing was widespread.

References

- Surprising Working From Home Productivity Statistics (2025) – Apollo Technical

- Surprising Working From Home Productivity Statistics (2025) – Apollo Technical

- Coronavirus drives blistering sales of Colorado mountain homes, sets 2020 as historic high mark – The Colorado Sun

- Census data shows how bad Colorado high country housing has gotten – The Colorado Sun

- Remote work and older people moving in helped drive population growth in San Luis Valley and Eastern Plains – Colorado Public Radio News

- Unpredictable Factors Deliver Record Setting 2020 Housing Market Across Colorado – Colorado Association of REALTORS®

- Staggeringly Low Housing Inventory Across Colorado – Colorado Association of REALTORS®

- Vacation Home Sales Surges During Pandemic – National Association of REALTORS®