Would you like to save this?

The Astor family built and acquired properties like architectural trophies, each more extravagant than the last, from Manhattan’s storied Fifth Avenue to the English countryside.

At Cliveden, their English estate, William Waldorf Astor transformed a grand Italianate mansion into a playground for the Edwardian elite, complete with terraced gardens and marble halls. Newport’s Beechwood was Caroline Astor’s throne room — an opulent “summer cottage” where the high and mighty jockeyed for a spot in her inner circle under crystal chandeliers and gilded cornices.

The Astor empire sprawled across continents, cultures, and architectural styles, each holding declaring their reign over wealth, taste, and a style few could rival, let alone dream up.

15. Two Temple Place

Two Temple Place on London’s Thames Embankment is William Waldorf Astor’s unapologetic nod to the Gothic Revival, built less as an office and more as a fortress of flair. Constructed in the 1890s, it was Astor’s sanctuary, a place where he could keep an eye on his business empire and indulge his rather dramatic tastes.

Designed by John Loughborough Pearson, Two Temple Place is brimming with carved wood, marble, and every storybook trope Astor could commission. Step through the doors and you’re met with a grand staircase wrapped in oak panels, where carvings of characters from literature and myth crowd together like they’re waiting for curtain call. Astor took the medieval vibes seriously: gargoyles, stained glass, and vaulted ceilings all make his “office” feel more like a Gothic hideout.

14. Astor Mansion

In its heyday, Mrs. Astor’s mansion at 350 Fifth Avenue was the epicenter of New York society, a palace of social power and architectural grandeur. Built in 1896 by Caroline Schermerhorn Astor — known as “The Mrs. Astor” — the residence was a fortress for her famously exclusive “Four Hundred,” the guest list that determined who was anyone in New York. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, the mansion featured a Renaissance Revival style with towering columns, high ceilings, and interiors dripping in frescoes and marble.

The ballroom could fit a hundred guests. Silk tapestries, European artworks, and chandeliers imported from France hung above a crowd that included Vanderbilts, Morgans, and the occasional European dignitary. In her space, Mrs. Astor ruled with absolute power, determining the fortunes of New York’s elite with either a nod of approval or an icy shoulder. In 1926, the mansion was demolished, but its memory lingers as the gold standard of New York high society.

13. Lansdowne House

Lansdowne House in London, once a stately neoclassical gem, boasts a past intertwined with the Astors’ penchant for prestige. Originally designed by architect Robert Adam in 1763 for the Marquess of Lansdowne, this mansion was textbook Georgian elegance, featuring soaring columns, intricate friezes, and a Palladian grace that made it one of Mayfair’s finest. By the 20th century, Lansdowne House had found itself in Astor hands, transforming its trajectory from aristocratic retreat to a hub of high-society influence.

In 1929, American heiress Nancy Astor took up residence here with her husband, Waldorf Astor. As a Member of Parliament, Nancy filled the house with a distinctly transatlantic energy, hosting parties that drew everyone from Winston Churchill to George Bernard Shaw. Lansdowne became a venue where policy and scandal rubbed shoulders, where “Lady Astor’s” wit was as legendary as her guest list. Today, part of Lansdowne House has been converted into a private club, and other parts were dismantled in the 1930s, but its history remains etched in London’s memory.

12. Ferncliff

Ferncliff, the Astors’ sprawling estate in Rhinebeck, New York, was their playground on the Hudson. Built in the late 1800s by William Backhouse Astor Jr., the property was designed in a grand, eclectic style with Italian Renaissance flair. Ferncliff included a 40-room mansion, carriage houses, and a private golf course.

Ferncliff became legendary under the eye of John Jacob Astor IV who expanded the estate. He threw parties, where guests from the worlds of politics, business, and high society mingled amidst a backdrop of marble columns and sprawling terraces. When Astor IV tragically died on the Titanic in 1912, the estate passed down to his descendants.

11. Rokeby

Rokeby, the eccentric Astor estate in Hudson Valley, has a charm that’s equal parts elegance and bohemian chaos. Originally built in the 19th century and passed down through generations, Rokeby represents an unpolished side of the Astor dynasty. Unlike the meticulously maintained Ferncliff or Beechwood, Rokeby became a relic of a more relaxed and slightly unruly branch of the family tree.

Set on 400 acres of rolling fields, it mixes Greek Revival and Gothic architectural styles, with turrets that add a quirky, castle-like feel. Margaret Astor Chanler, an Astor by marriage, took up residence here in the late 1800s, hosting writers, artists, and European exiles. Still owned by Astor descendants, Rokeby holds a distinctly counter-culture vibe for an estate linked to Gilded Age wealth.

10. Beechwood

Would you like to save this?

Newport wasn’t Newport without Beechwood, the mansion Caroline Astor turned into her summer headquarters and “cottage” in the loosest sense. Built in 1851, this Italianate stunner went through a makeover that transformed it into an Astor-worthy paradise.

Marble halls, grand staircases, and a gilded ballroom the size of a tennis court made it the ultimate summer party house for the 400 — New York’s most elite social circle, handpicked by Mrs. Astor herself. The house is filled with Caroline’s influence — she had rooms arranged specifically for guests to see and be seen, even hiring a staff to ensure each detail of the parties met her high standards. Beechwood was a throne room for a woman who ruled New York society with an iron fan.

Portraits of ancestors lined the walls, reminding everyone of the Astor legacy. Later owners converted the mansion into a “living history” museum, where actors portrayed the Astor family and staff, giving visitors a taste of Gilded Age life. Though modernized, Beechwood’s bones hold the glamour of an era defined by power, parties, and the unmistakable presence of The Mrs. Astor herself.

9. Elm Court

Elm Court is what happens when two powerhouses collide: the Astors and the Vanderbilts. Built in 1886 as a wedding gift for Emily Astor and her husband, William Vanderbilt, this Lenox, Massachusetts mansion was no ordinary retreat.

Elm Court was designed as a “cottage,” though there’s nothing quaint about its sheer size or its layered, eclectic style, blending Shingle, Tudor, and Colonial Revival styles. The estate stretched over 55,000 square feet, with 106 rooms designed to host gatherings that would make even Mrs. Astor envious. The architecture is a love letter to the American Shingle style, with rambling roofs and asymmetrical facades that make it feel almost homey — at least by Astor standards.

But the interiors don’t hold back: grand fireplaces, ornate woodwork, and a drawing room that seemed designed to intimidate. The estate sprawls across rolling Berkshire hills, with views and gardens that made the Gilded Age aristocracy feel closer to nature while remaining wrapped in luxury.

8. Cliveden

Across the pond, the Astors made Cliveden their mark on the English countryside. Built in 1666, this mansion saw its share of owners before falling into the hands of William Waldorf Astor in 1893, who transformed it into an Edwardian playground for the elite.

Cliveden’s Italianate beauty, with its towering columns and terraced gardens, looks every bit the part of an English noble’s estate, complete with tapestries, chandeliers, and lavishly decorated bedrooms fit for a royal — literally, as Cliveden often hosted the likes of Queen Victoria. While it might seem worlds away from New York, Cliveden is every inch an Astor home.

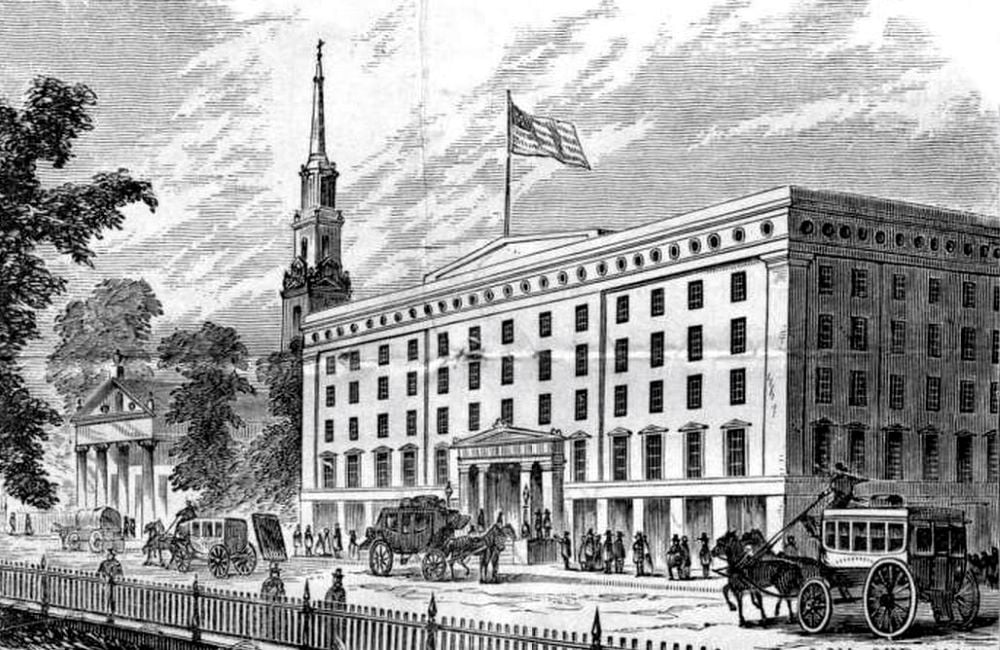

7. Astor House

Astor House, built in 1836 by John Jacob Astor, was New York City’s first five-star hotel experience before anyone knew what “five-star” meant. Designed in the Greek Revival style, Astor House featured marble columns, massive interiors and pulled out all the stops.

Presidents, European royalty, and a who’s-who of American society bought into Astor’s marble-and-mahogany vision of paradise. For nearly a century, Astor House set the standard for luxury hotels in the U.S. before being demolished in 1913.

6. Hever Castle

In an unexpected twist, Hever Castle, a 13th-century English stronghold, found itself under the ownership of William Waldorf Astor in 1903. Originally the childhood home of Anne Boleyn, Hever was more fortress than mansion, but Astor saw its potential. He spent millions transforming the place into a romantic, Tudor-inspired retreat, a painstakingly restored slice of history complete with towers, moats, and ivy-clad walls that looked straight out of a medieval storybook.

Astor turned Hever Castle into his personal Camelot, adding elaborate gardens, a lake, and Italian-inspired sculptures to its medieval architecture. Tapestries, antique furniture, and intricately carved wooden panels give each room a sense of history.

5. St. Regis New York

The St. Regis New York, founded in 1904 by John Jacob Astor IV, was a glimmering beaux-arts beacon at Fifth Avenue and 55th Street in midtown Manhattan. Astor wanted a hotel that combined European elegance with modern amenities, and he didn’t skimp: French marble, gilded mirrors, ornate chandeliers, and world-class service.

The St. Regis quickly became a haunt for high society, a place where cocktails at the King Cole Bar — home of the original Bloody Mary — set the standard for nightlife. Astor’s penthouse suite is part residence, part museum, with a design aesthetic that toes the line between Edwardian grandeur and modern cool. Views of Central Park sprawl out from floor-to-ceiling windows. Over a century later, the St. Regis still shines as a place where Old New York meets Manhattan hustle.

4. Château de Brissac

William Waldorf Astor took his penchant for palatial living international, snapping up the Château de Brissac in 1890. This Loire Valley castle dates back to the 11th century and has more towers, spires, and rooms than even the Astors could likely keep track of.

Astor saw it as a jewel of French history that could shine even brighter. He overhauled the interiors, filling them with Louis XV furniture, tapestries, and ornate chandeliers. The château boasts over seven stories, making it one of the tallest castles in France, with lush grounds and vineyards stretching across the valley.

Its rooms are pure theater, with ornate gilding, frescoes, and a small private chapel. Astor turned it into a stage for his European ambitions, hosting lavish gatherings with French nobility. Brissac was Astor’s own Versailles, blending French history with American showmanship.

3. The Breakers

While technically a Vanderbilt venture, The Breakers had an Astor twist: John Jacob Astor IV married into the family, meaning this summer palace was very much in Astor’s orbit. Built in 1895, this 70-room Italian Renaissance-style “cottage” on Newport’s cliffs is an unapologetic nod to Gilded Age splendor.

Massive, intimidating, and dripping in marble, The Breakers’ gold-leafed walls and frescoed ceilings speak to a family for whom “too much” was never quite enough. Each room seems designed to outdo the last, with French furniture, gilded moldings, and a massive dining room. The Breakers was a palace in every sense of the word.

2. Chiswick House

Chiswick House, an 18th-century Palladian masterpiece just west of London, found its way into Astor history thanks to Nancy Astor, whose family acquired a significant interest in the estate during the early 20th century.

Originally designed in the 1720s by Richard Boyle, the 3rd Earl of Burlington, the villa was a nod to Italian architecture with English restraint. This was Britain’s first true attempt at neoclassicism, and Chiswick became a laboratory for Burlington’s architectural experiments, setting the stage for the grand country houses that followed. Under the Astors, Chiswick House morphed from intellectual salon to social haven, blending the family’s American flair with British high society’s preferences.

Nancy Astor, famed for her razor-sharp wit, used Chiswick as a gathering ground for her influential circle. With its vast gardens designed by William Kent, complete with winding paths and classical statues, it was the perfect setting for Astor-style entertaining.

1. Waldorf Astoria

Nothing sums up the Astor legacy quite like the Waldorf Astoria. Originally built in 1893, this hotel was the pinnacle of Gilded Age glamour, a place where European royalty and American nouveau riche crossed paths. Designed to outshine every other building on Fifth Avenue, the Waldorf Astoria boasted grand ballrooms, lavish suites, and a lobby that felt like the inside of a cathedral.

John Jacob Astor IV poured his ambition into every inch of the place. The Waldorf was the Astor family’s crowning achievement, a monument to their power and taste. And when the original was demolished to make way for the Empire State Building, a new Waldorf Astoria rose, proving that Astor’s vision could transcend bricks and mortar.