Would you like to save this?

Wide horizons, lonely highways, and sky so dark the Milky Way looks close enough to touch—southeast Colorado still holds places where quiet reigns.

We gathered 10 communities where populations stay small, neighbors sit miles apart, and night sounds come from coyotes rather than traffic.

Each stop rewards visitors and future residents alike with a mix of history, prairie scenery, and the kind of stillness that deepens a star-filled evening. Hidden schoolhouses, century-old barns, and crumbling adobe walls tell stories of cattle drives and rail days long gone.

While Denver and Colorado Springs sprint ahead, these towns keep time with the windmill. Here’s where to find them, counted down from number 10 to number 1.

10. Lycan – A Lone Grain Elevator Surrounded by 360° of Short-Grass Prairie

Lycan supports fewer than twenty-five year-round residents who share a handful of broad, multi-acre homesteads. Photographers linger here to capture the sun setting behind the town’s solitary concrete grain elevator, wind pumps, and endless waves of buffalo grass.

Local livelihoods revolve around dryland wheat, cattle grazing, and seasonal hunting leases that bring a brief uptick in traffic each fall.

Recreational options lean toward the self-reliant: bird-watching for burrowing owls, long-range stargazing unobstructed by light pollution, and prairie hikes where antelope outnumber people.

With the nearest stoplight forty miles away in Springfield, modern conveniences sit firmly on the horizon. That distance, paired with a total absence of commercial zoning, keeps Lycan wrapped in a peaceful hush.

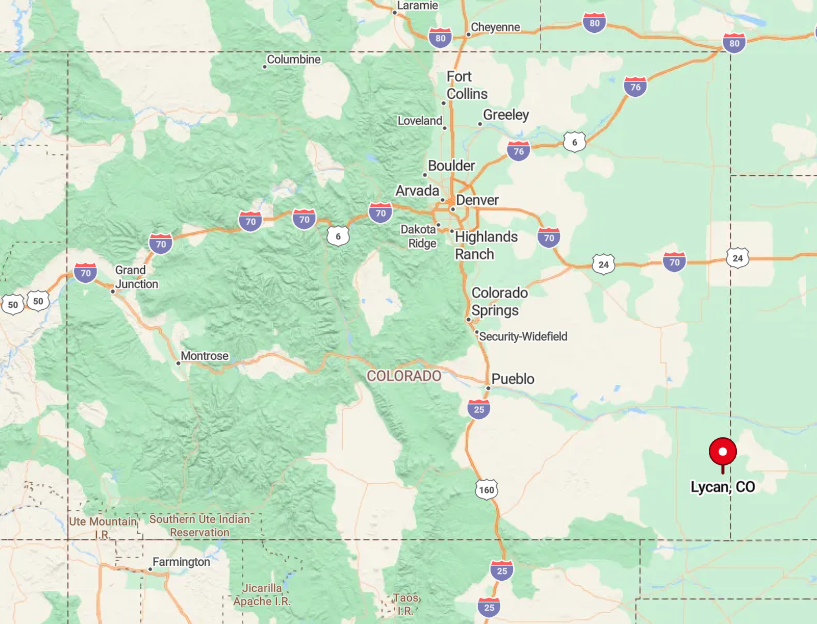

Where is Lycan?

The settlement rests in far-eastern Baca County, four miles north of the Oklahoma border along Colorado Highway 89. Flat land stretches to every point on the compass, so wind and meadowlark songs travel unbroken for miles.

Travelers reach Lycan by following U.S. 287 south from Lamar, then branching east on lightly trafficked county roads where cellphone service fades. Once the pavement ends, a lone water tower announces the edge of town.

9. Buckeye Crossroads – Where Two Dirt Roads Meet and Then the World Falls Silent

Only eight residents keep watch over Buckeye Crossroads, a near-ghost settlement marked by a single four-way junction of graded gravel. The main pastime involves exploring adjacent units of Comanche National Grassland, where fossilized dinosaur tracks hide in the chalky creek beds and spring wildflowers blanket the tablelands.

Work centers on cow-calf operations and custom hay cutting, with an old fuel tank now serving as the unofficial community noticeboard. Visitors often pause for a thermos lunch under the shade of a lone cottonwood, listening for the distant low of cattle and the whistle of prairie winds.

No retail exists, and the closest convenience store sits thirty-five minutes away in Walsh. That emptiness amplifies every birdsong and makes nightfall arrive with a velvet quiet.

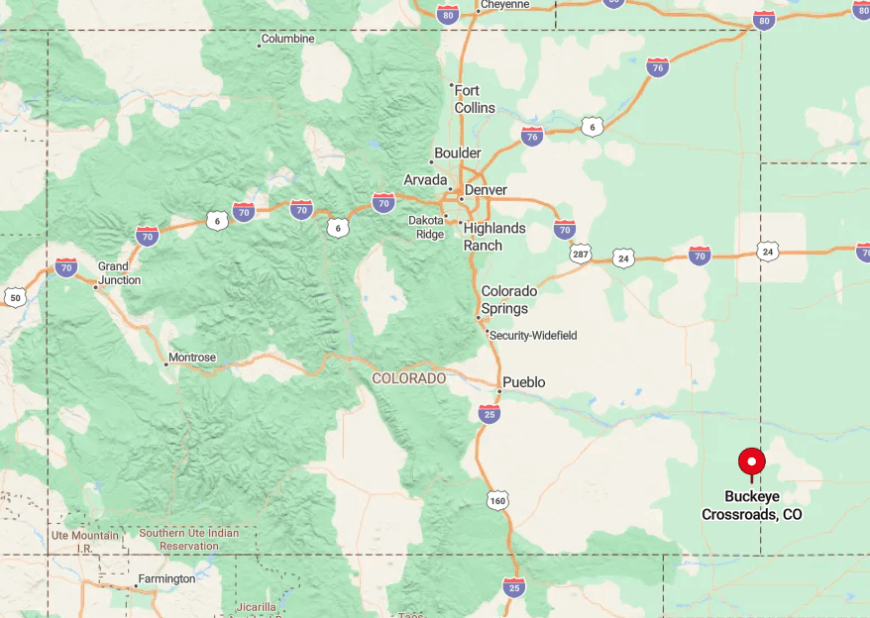

Where is Buckeye Crossroads?

The crossroads lies twenty-one miles east of U.S. 385 in extreme eastern Baca County, accessible only by unsigned county routes that turn to rutted clay after rain. Surrounding folds in the short-grass break the line of sight, muffling noise from any distant tractor.

GPS units frequently lose signal, so seasoned travelers rely on odometer readings and windmill landmarks. Once reached, the two intersecting roads form a tiny tab on the map—a fitting gateway to thousands of empty acres.

8. Stonington – An Empty Rail Siding Turned Pocket of Prairie Seclusion

Stonington claims roughly twenty full-time inhabitants scattered among abandoned elevators, silo walls, and tumbleweed-lined tracks of the old Missouri Pacific line.

Rail buffs walk the ghost siding to photograph weathered boxcars while birders focus binoculars on flocks of migrating sandhill cranes skirting the nearby Cimarron River corridor.

Agricultural custom work and grain storage still generate seasonal paychecks, though most locals supplement with online gigs that don’t require a commute. Hidden picnic tables beside a crumbling depot foundation offer shade and history lessons in equal measure.

With homesteads separated by mile-long section roads, neighbors wave rather than knock. That spacing, plus a train schedule reduced to twice-weekly freight, leaves Stonington cloaked in near constant stillness.

Where is Stonington?

Would you like to save this?

The siding sits twelve miles south of Walsh on County Road SS, then three miles west along the unmarked tracks. Rolling prairie creates a natural sound buffer, letting even a distant pickup fade quickly.

Access comes easiest via State Highway 160, though the final stretch follows dirt graded just often enough to stay passable for ranch trucks. Visitors should top off fuel beforehand, as the nearest service station is back in Walsh.

7. Timpas – Cottonwood-Shaded Acres Along a Quiet Stretch of the Old Santa Fe Trail

About seventy people call Timpas home, many living on one- to five-acre ranchettes tucked among cottonwoods along the Timpas Creek bottom. Writers and painters appreciate the easy walk to stone chimney ruins from stagecoach days, while anglers drift worms through deep creek pools for channel catfish.

Hay farming and small-scale cattle operations dominate the tax rolls, though a few residents earn wages in La Junta fifteen minutes away. Even so, Highway 50 traffic fades quickly behind earthen berms that flank the creek, and cell reception drops in the draws.

Evening brings the rustle of cottonwood leaves and the glow of oil-lamp patios rather than city glare. Those muted sounds give Timpas a refuge feel despite its modest proximity to pavement.

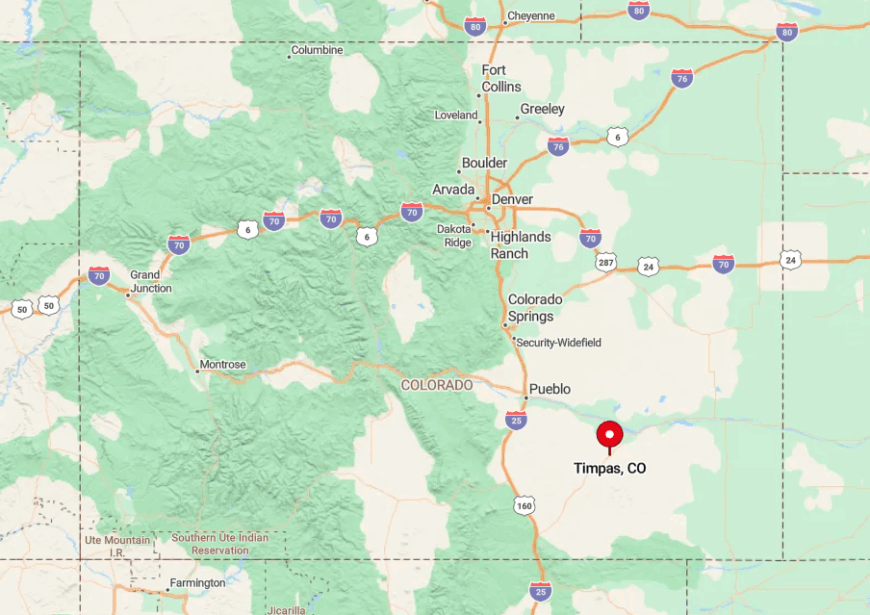

Where is Timpas?

The hamlet sits nine miles south of La Junta on U.S. Highway 350, then a quick jog east on County Road 805. Creek bluffs shield the settlement from highway noise, creating pockets where radio static replaces FM music.

Travelers reach it easily by car, yet a bend in the old Santa Fe Trail keeps Timpas hidden from hurried motorists. Once past the cottonwood canopy, gravel lanes loop quietly among small farms.

6. McClave – Bent County’s Wide-Lot Farm Community Hidden Behind Irrigation Canals

McClave hosts almost six hundred residents, though its generous lot sizes and shelterbelt trees lend a far smaller-town vibe. Families gather for Friday night six-man football under lights that reflect off nearby alfalfa fields, and birdwatchers paddle the John Martin Reservoir inlet in search of white pelicans.

Farming—chiefly corn, hay, and winter wheat—powers the local economy, aided by a century-old canal network that feeds center-pivot sprinklers. Hidden gems include a Depression-era sandstone gym still used for community dances and a roadside farm stand that sells melon ice cream each July.

Despite U.S. 50 lying a mere six miles away, canal berms and thick windbreaks dampen sound and sight lines from the highway. The result is an island of greenery and calm set inside an ocean of cropland.

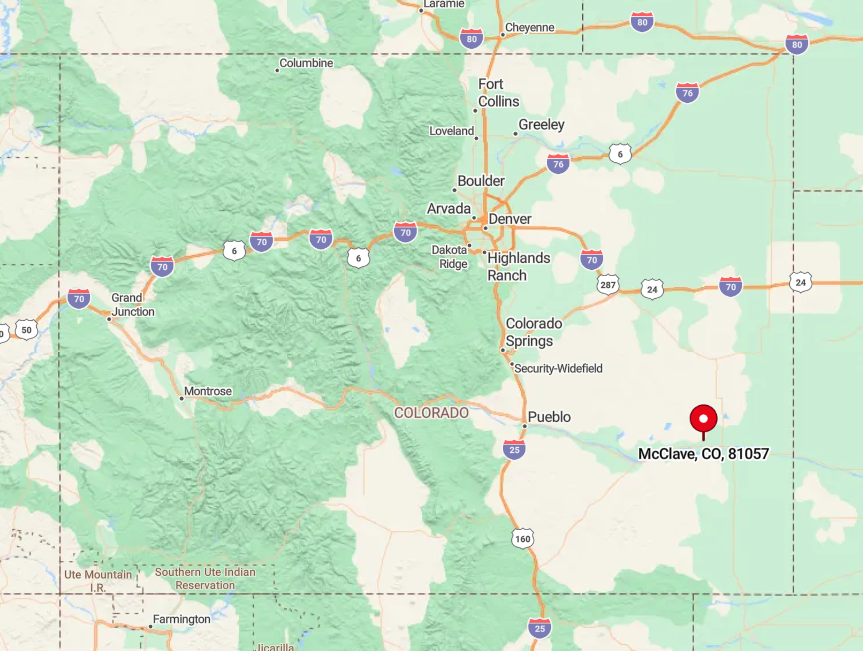

Where is McClave?

The village stands twelve miles west of Lamar, just off State Highway 196 and bordered by the Fort Lyon Canal. Dense rows of mature ash and elm trees form a living wall that screens the larger world.

Drivers exit U.S. 50 at Hasty, cross the Arkansas River, then follow a gentle curve through pasture to reach town. Rail service bypasses McClave entirely, adding one more layer of quiet.

5. Thatcher – A Cluster of Adobe Homes Nestled Beneath Raton Mesa’s Rugged Rim

Fewer than eighty residents occupy Thatcher’s adobe cottages and rust-colored ranch houses that cling to the base of Raton Mesa. Hikers follow faint game trails up the piñon-dotted hillsides for panoramic views stretching into New Mexico, while history buffs poke around the stone walls of a long-closed general store.

Cow-calf ranching and custom fencing form the main income streams, supplemented by guided elk hunts each October. A tiny, well-kept cemetery and an open-air chapel provide unexpected stopping points for photographers chasing evening light.

The mesa’s bulk absorbs highway clatter from distant U.S. 350, and cell towers can’t quite peer over the rim. Thanks to that natural barrier, Thatcher’s nights remain dark and wonderfully still.

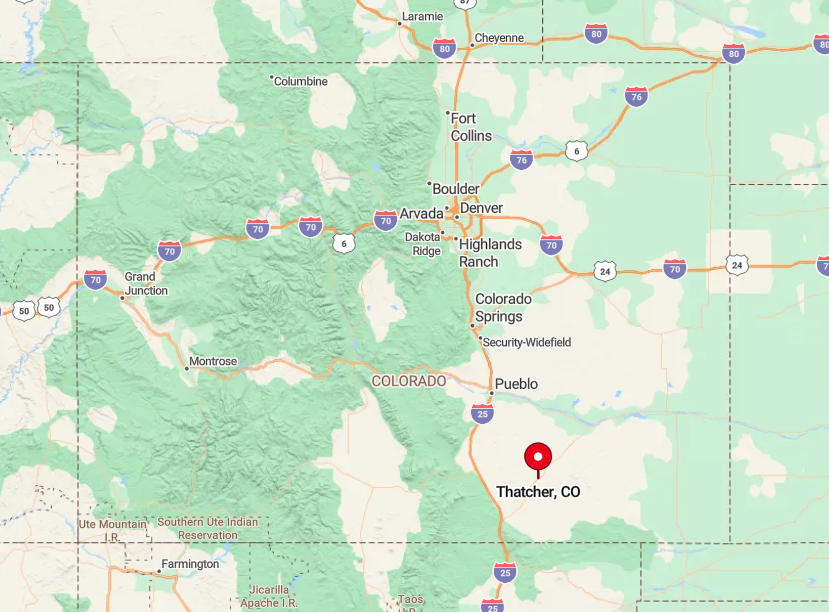

Where is Thatcher?

The settlement lies thirty miles southwest of La Junta along State Highway 350, then three miles west on County Road 18. The roadway dips into sagebrush draws that cut radio reception and hide approaching vehicles until the last minute.

Visitors typically exit Interstate 25 at Trinidad, drive northeast through pinched canyons, and crest a ridge where Thatcher appears like a mirage. Without freight lines or bus routes, private wheels provide the only reliable access.

4. Delhi – One-Room Schoolhouse and Miles of High Plains Stillness

Delhi’s population hovers near fifty, most living on cattle spreads stitched together by decades of family succession. Travelers spot the iconic white-washed schoolhouse first, then realize it doubles as a polling station and holiday gathering hall.

Work centers on ranching, supplemented by seasonal prairie dog hunts that bring in small guide fees. The Purgatoire River meanders quietly nearby, offering kayak floats through soft sandstone banks that few outsiders ever see.

With the nearest gas pump twelve miles north in Hoehne, even passing motorists think twice before detouring. That light traffic, combined with vast grazing allotments, lets Delhi keep its high-plains hush intact.

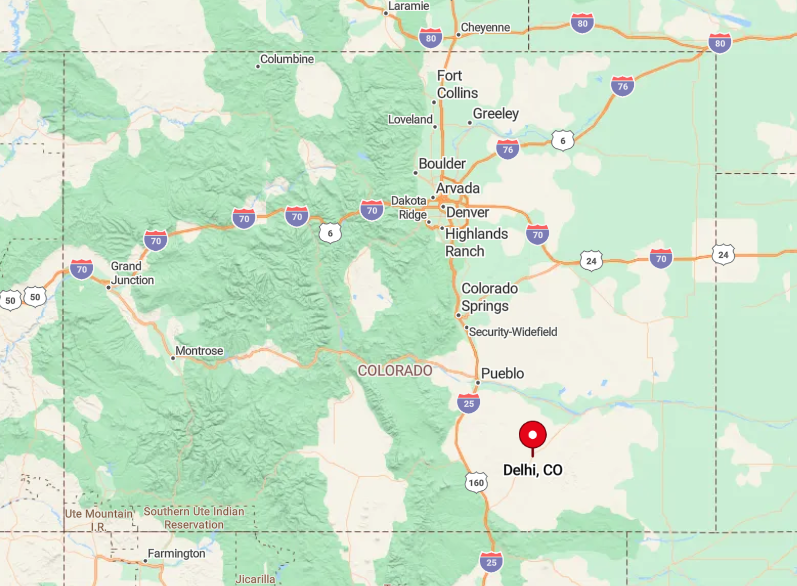

Where is Delhi?

The community straddles U.S. Highway 350 between Trinidad and La Junta, yet sits far enough from larger towns that the road rarely carries more than a dozen cars an hour. Broad pastures absorb engine noise long before it reaches the cluster of homes.

Amtrak whistles drift faintly from the Southwest Chief line ten miles south, but freight never stops here. Reaching Delhi simply requires a full tank and willingness to share the road with pronghorn.

3. Model – Sagebrush, Sandstone Bluffs, and Nothing Else for Twenty Miles

Roughly one hundred residents make their homes on forty-acre parcels scattered across Model’s undulating sage flats. Outdoor pursuits include rockhounding for petrified wood in nearby arroyos and scrambling up low sandstone bluffs that hide ancient petroglyphs.

Ranch work, small-scale renewable-energy installations, and mail-order crafts provide income in a place where commercial storefronts never materialized. Local lore tells of a 1930s promoter who envisioned a “model” farming community; his street grid remains on old plats yet only wind and tumbleweed occupy most lots.

Protective ridgelines block sightlines to Interstate 25 fifteen miles west, so the night sky keeps its full spread of constellations. With no streetlights or gas station glow, Model earns its solitude.

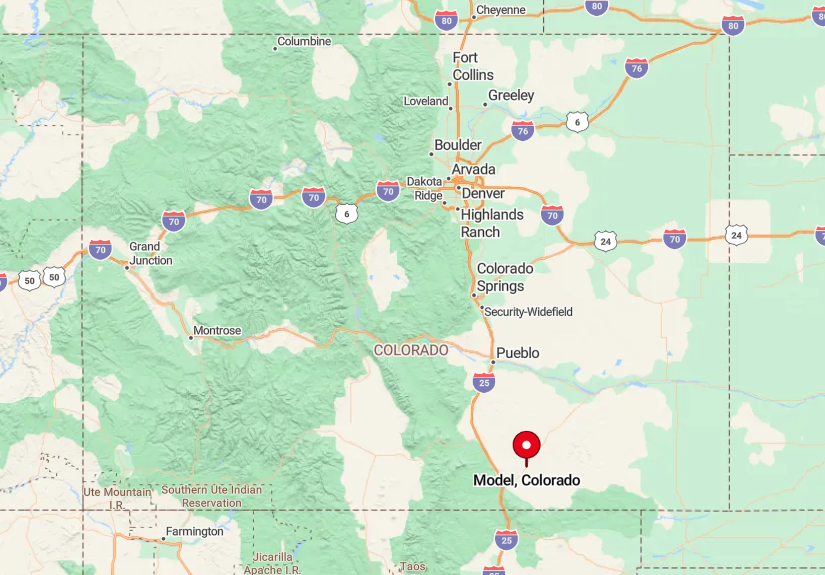

Where is Model?

The area sits off U.S. Highway 350, approximately thirty miles northeast of Trinidad, reached via County Road 43.2. As pavement gives way to caliche, mesas rise on either side, forming visual blinders that reinforce isolation.

GPS leads drivers through a checkerboard of state trust and private land, but services end back at the interstate ramps. Carry water and a spare tire—tow trucks can take hours to arrive.

2. Brandon – Weathered Grain Bins Guarding Kiowa County’s Least-Traveled Highway

Brandon’s resident count fluctuates around fifty, many of whom maintain ties to multi-generation wheat farms stretching to the horizon.

Visitors photograph towering tin-clad grain bins that catch late-day sun like muted silver beacons, then wander down a half-abandoned main street where faded signs still advertise five-cent coffee.

Wheat hauling and custom combine crews remain the primary economic engines, joined by a cooperative seed-cleaning operation run out of a corrugated shed. Summers bring pickup baseball games on a dirt diamond mowed weekly by volunteers, while autumn means chasing pheasants through knee-high stubble.

State Highway 96 passes through but sees more tumbleweed than traffic, leaving the storefronts in a near-continuous hush. Open prairie in every direction ensures Brandon hears little beyond grain augers and meadowlark trills.

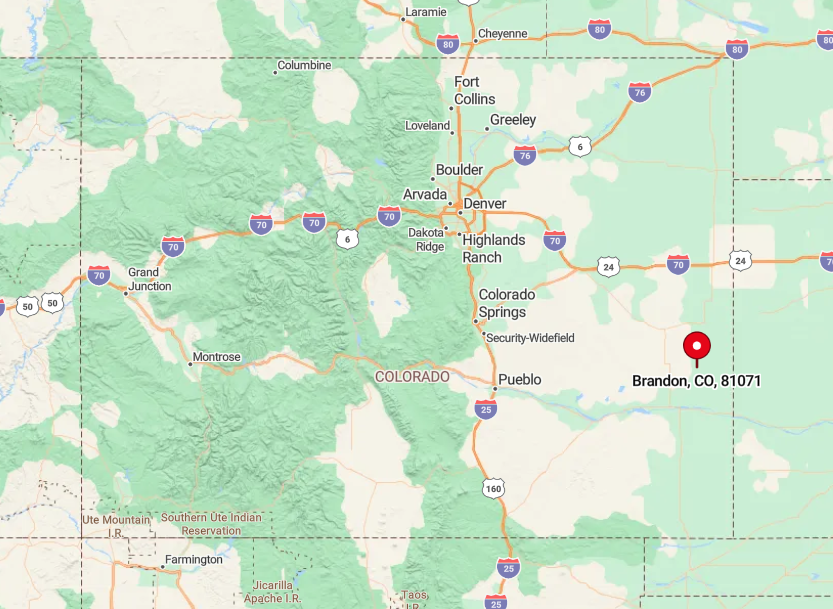

Where is Brandon?

The settlement sits twenty-seven miles east of Eads on Highway 96, with no alternate paved routes for more than forty miles. Sparse traffic and a lack of crossroads amplify the feeling of remoteness.

Drivers fuel up in Eads, then glide past fenceline mile markers until the grain bins rise from the horizon. Railroad tracks that once bustled with cattle cars now host only the occasional maintenance wagon, sealing Brandon’s quiet fate.

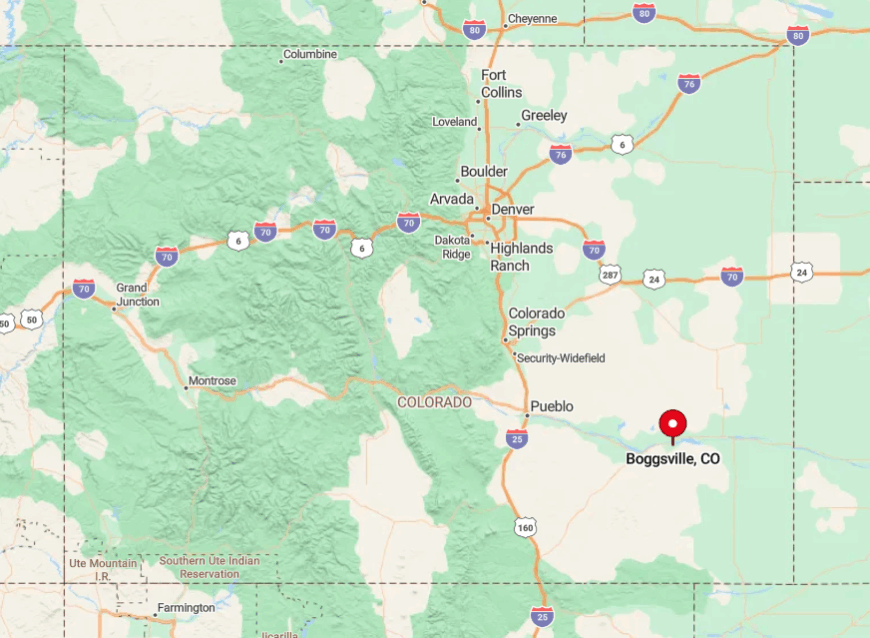

1. Boggsville – Historic Adobe Ruins and Cottonwood Groves on a Quiet Bend of the Arkansas

Would you like to save this?

Boggsville holds fewer than thirty residents, most clustered near the preserved 1860s ranch headquarters where Kit Carson spent his final months. Day visitors explore restored adobe homes, irrigated heritage gardens, and interpretive trails that trace the original stagecoach route along the Arkansas River.

Livelihoods rely on irrigated alfalfa, heritage-tourism stipends, and wildlife habitat projects that protect the riparian corridor for bald eagles and beaver. A picnic under hundred-year-old cottonwoods lets guests hear nothing but river murmur and rustling leaves, while nightfall often brings the hoot of great horned owls.

Although Las Animas sits only five country miles north, a maze of levee roads and farm gates discourages casual traffic. That buffer, together with preserved open space, grants Boggsville a tranquil, time-capsule atmosphere.

Where is Boggsville?

The site lies south of Las Animas off Colorado State Highway 101, then west on a gravel loop that parallels the Arkansas River. Cottonwood groves screen the historic core from the highway, so engines fade quickly into the river’s white noise.

Visitors often arrive by kayak or bicycle, using the levee trail that links John Martin Reservoir to Bent’s Old Fort. No public transit reaches the area, so those seeking Boggsville’s quiet history must arrive under their own power and leave modern bustle behind.