Would you like to save this?

The high-country counties east of Arizona’s spine hide pockets of quiet that most maps barely whisper about. Within pine-rimmed meadows, volcanic foothills, and hidden river canyons sit a handful of settlements where night skies still rule and the nearest chain store can sit an hour away.

Our roundup highlights villages where elk still saunter down main lanes, gravel roads outnumber paved ones, and neighbors know one another by pickup truck rather than profile photo.

These communities share a talent for staying tucked away, whether by dirt track, forest buffer, or sheer distance from the interstate. We explore what life looks like in each spot—its people, pastimes, and practical considerations—then spell out exactly where the dot lies on the map.

Eastern Arizona might be vast, but these 25 towns prove it’s also full of corners where genuine seclusion survives.

25. Concho

Scattered across sagebrush flats and juniper hills, Concho’s quiet presence remains a mystery to most passing drivers. Its original roots as a 19th-century Mormon settlement still echo in the weathered adobe homes and irrigation ditches that lace the land.

Mild summers and cold, dry winters lend the town a sense of stasis—like time forgot to keep ticking. Fishing at Concho Lake, visiting the old schoolhouse, or birdwatching near the creeks round out a day here, while ranching and retired residents anchor the economy.

It’s the kind of place where even the wind seems to slow down to take in the stillness.

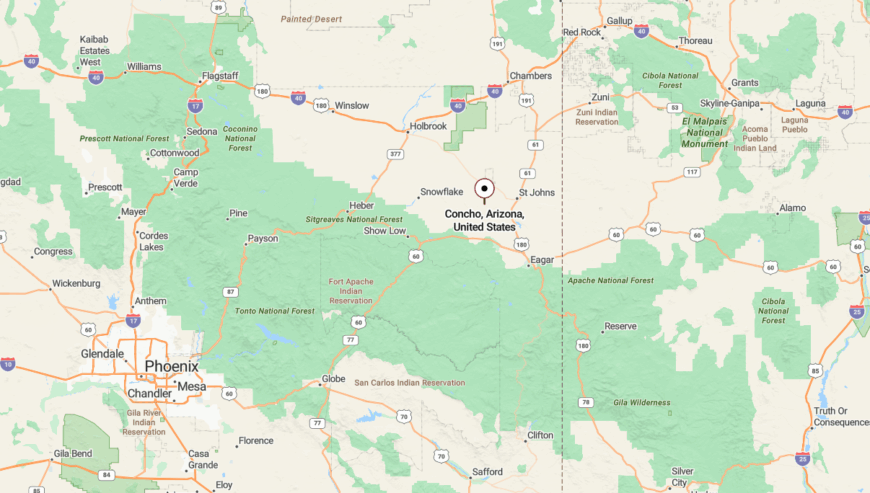

Where is Concho?

Concho sits in Apache County, northeast of Show Low, reached via AZ-61 and a series of wide, wind-swept turns. As you leave the last sign of gas stations behind, the road straightens into big sky and open range.

Low hills and distant ridgelines form a quiet cradle around the town, shielding it from sprawl and through-traffic. It’s the kind of place that quietly unfolds once you’re in it—never demanding to be found.

24. St. Johns

Despite being the Apache County seat, St. Johns exudes more frontier hush than civic bustle. Tucked in a river-carved basin and bordered by red cliffs, the town’s adobe history and Mormon pioneer past linger in its air.

The scent of woodsmoke curls above historic homesteads while kids fish in Lyman Lake and locals swap stories at the general store. Government work and ranching sustain most residents, though few outsiders ever venture this far for work or leisure.

Even the courthouse seems to whisper rather than shout.

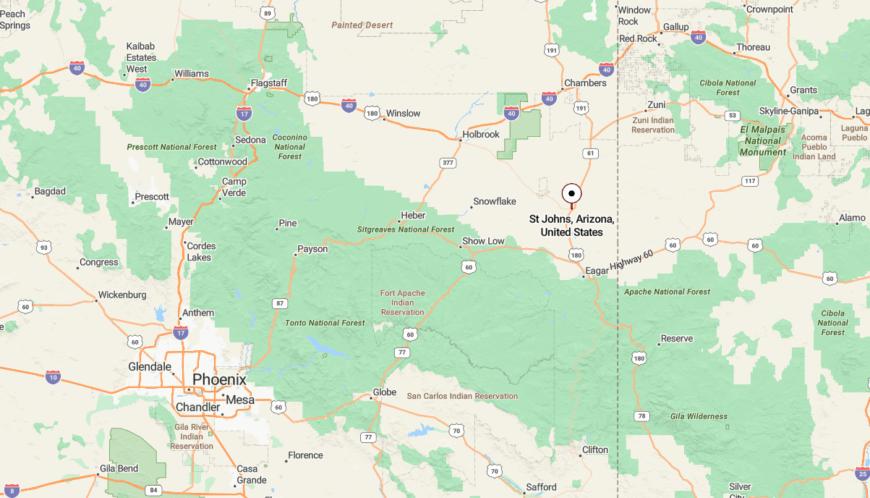

Where is St. Johns?

St. Johns is in northeastern Arizona, near the New Mexico border, nestled along U.S. 180/191 about 40 miles north of Springerville. The approach passes vast mesas, grazing land, and wind turbines spinning in silence.

Though paved, the road feels remote, and the town’s low profile only deepens its sense of remove.

23. Vernon

Pine thickets and rolling pasturelands shield Vernon from the stream of travelers passing nearby on U.S. 60. A cluster of mailboxes, a single gas pump, and a quiet elementary school are about all that mark its footprint.

Locals hike into the Sitgreaves forest, gather for firehouse potlucks, or ride horses across the grassy meadows that surround the few gravel lanes. With no streetlights, few businesses, and an unofficial population just over a hundred, Vernon embraces simplicity.

The stars here seem to come a little closer.

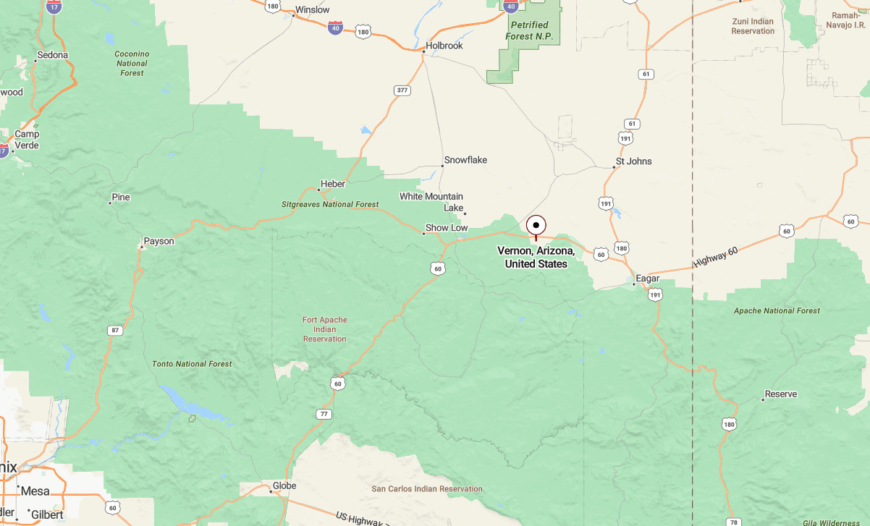

Where is Vernon?

Would you like to save this?

Vernon is tucked into the high country of Apache County, 18 miles east of Show Low via US-60 and a short turn onto county backroads. The highway opens into forest, then thins into grassy clearings, where elk outnumber neighbors.

Far from interstates and strip malls, Vernon hides in plain sight. Most only pass by—few realize just how quietly the town waits beyond the trees.

22. Linden

On the western shoulder of the White Mountains, Linden stretches between ponderosa groves and high-country pasture with just enough space between homes to hush the world’s noise. Once a logging outpost, now a mix of ranch life and low-key retirees.

Locals explore Turkey Creek Trail, ride horses at daybreak, or browse homegrown goods at roadside produce stands. Income comes from nearby Show Low jobs or self-sufficient homesteads set back from the road.

You might miss it in the blink of a drive—but its stillness lingers.

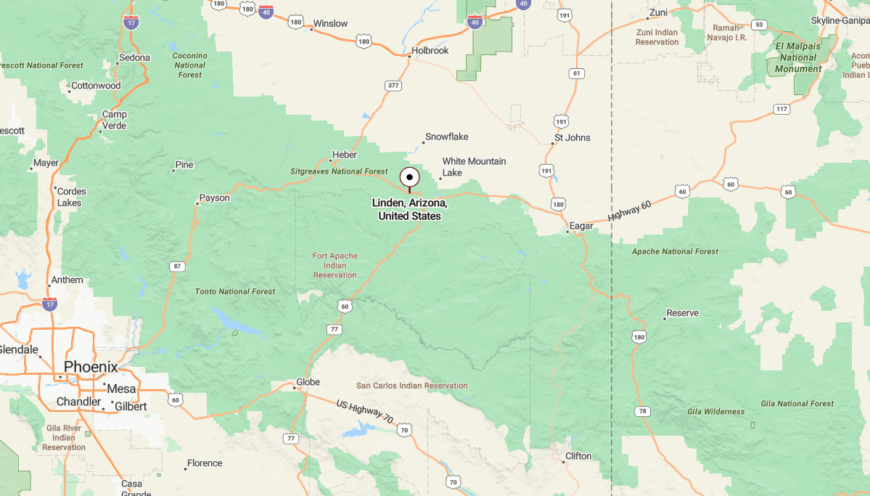

Where is Linden?

Linden lies just west of Show Low in Navajo County, lightly threaded along AZ-260. As you drive through, pine shadows fall long over the road, and signs of settlement seem to appear and vanish with the trees.

Its soft boundaries and absence of a defined town center let it blend into the land. Linden doesn’t announce itself—it welcomes those who slow down enough to notice.

21. McNary

Nestled amid spruce forests at nearly 7,300 feet, McNary is more whisper than town—built originally for lumber mill workers, now wrapped in mossy quiet and lingering mist. Charred logs from the old mill site tell part of the story.

Trout fishing in Hawley Lake, slow drives through forested backroads, and snowy owl sightings replace commerce or commotion. Though part of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, much of McNary’s economy faded with the mill’s closure.

What remains is a place that breathes only as loud as the trees.

Where is McNary?

McNary rests in Apache County, just south of Pinetop-Lakeside off AZ-260, barely marked on many maps. Drivers blink through it in under a minute, unless turning toward Reservation Lake or Greer.

Snow lingers longer here, and the road often feels like a ribbon leading into the woods and out of time.

20. East Fork

Just upriver from Whiteriver and nestled into a lush valley of the Fort Apache Reservation, East Fork is more community than town—quiet, tight-knit, and bound to the land. It’s the kind of place that sees few visitors but holds deep meaning for those who call it home.

People fish for trout in the White River, tend traditional gardens, or gather for small cultural events passed down for generations. Employment mostly comes through the tribal government or seasonal forest work.

The hum of riverwater replaces the sound of traffic.

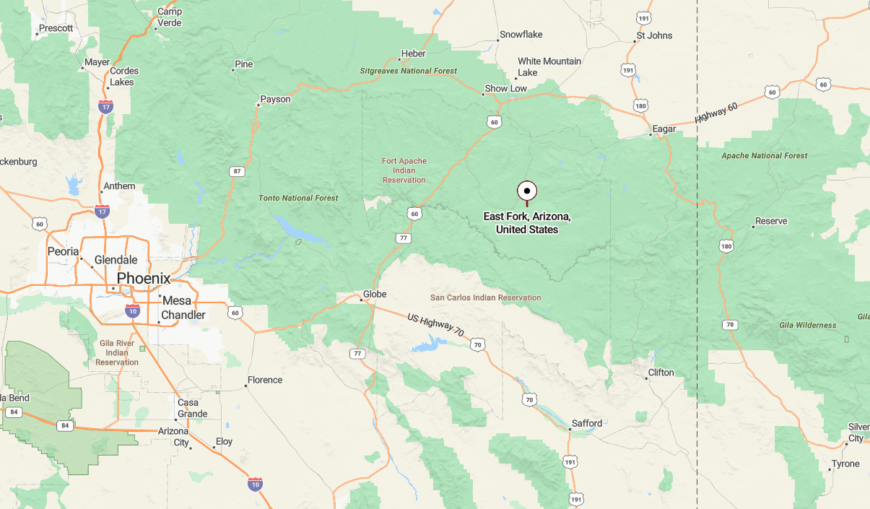

Where is East Fork?

East Fork is located in southern Gila County on the Fort Apache Reservation, southeast of Pinetop via White River Road. The drive in follows the river through a thickening forest, where signs dwindle and cell service disappears.

With canyon walls and wooded ridges on all sides, the town feels enclosed by the land itself. You don’t stumble upon East Fork—you arrive slowly, and leave even slower.

19. Whiting Knoll

Perched at 9,000 feet and tucked between alpine meadows and fir-covered ridges, Whiting Knoll is more clearing than town—but it holds a presence all its own. A scattering of cabins and old fire roads dot the slope, with no signage and no sense of urgency.

Days pass slowly here—filled with hikes into untouched forest, tracking elk prints in soft soil, or watching afternoon storms curl over the White Mountains. No commerce exists, just seasonal cabins and a ranger lookout that still watches the treetops like it’s 1952.

It’s the kind of place where even your voice feels too loud—so you start whispering, without really knowing why.

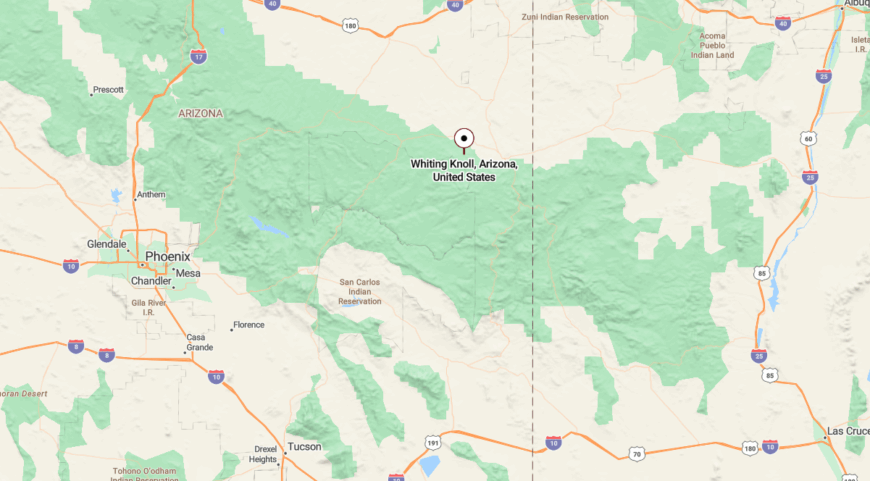

Where is Whiting Knoll?

Whiting Knoll sits in eastern Apache County, south of Greer, tucked into a ridge above the East Fork of the Little Colorado River. Reached by Forest Road 245 off AZ-373, the route narrows quickly and climbs through thick spruce.

It’s barely marked on most maps, but that’s part of the appeal—by the time you arrive, it already feels like the world has fallen away.

18. Eagar

Though adjacent to Springerville, Eagar feels worlds removed—its neighborhoods spread thin across grassy benches and forested ridgelines. The scent of juniper hangs in the air, and mountain silhouettes mark every horizon.

Locals ride ATVs into the national forest, fish the Little Colorado, or visit the old El Rio Theater. Ranching and a few government jobs support most families, but the vibe is unmistakably “quiet hometown.”

Eagar holds its own pace—and doesn’t rush to meet anyone else’s.

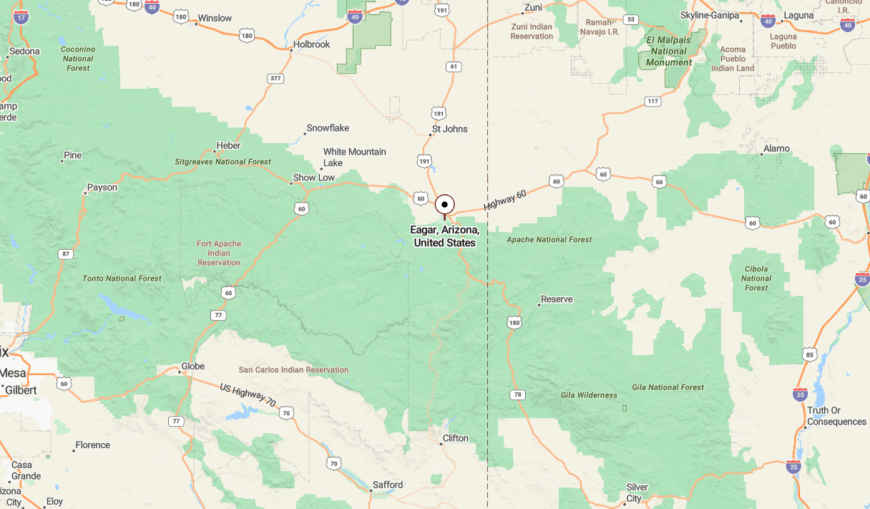

Where is Eagar?

Eagar lies in the Round Valley of Apache County, just south of Springerville along US-180. Though the highway brushes past, the town itself spills quietly across foothills and timbered plateaus.

With forests to the south and long open views to the north, Eagar offers seclusion not from distance—but from pace. You’re never far from the world, but it sure feels like it.

17. Carrizo

Carrizo lies hidden in the rugged folds of the Fort Apache Reservation, where canyons and cottonwoods embrace a tightly held piece of land. Few signs mark its presence, and even fewer pass through.

Residents tend sheep, grow traditional gardens, or live off seasonal wages. Trails wind into the surrounding hills, and spring-fed creeks weave between pinon stands.

It’s a place with deep roots and soft footsteps.

Where is Carrizo?

Carrizo is hidden in the rugged folds of Navajo County, south of AZ-77, deep within the Fort Apache Reservation. The route in winds across dry riverbeds and into canyon-shadowed roads that feel untouched by time.

Surrounded by ridges and scrub-covered mesas, Carrizo is a town wrapped in geography. It doesn’t ask to be noticed—it simply endures, out of sight and out of hurry.

16. Rye

Would you like to save this?

This blink-and-you’ll-miss-it settlement sits at the base of the Mazatzal Mountains, straddling the line between desert and pine. Rye’s few buildings—mostly cabins and ranch houses—cling to the scrub-covered hillsides.

Locals fish the East Verde River, visit the old Rye General Store, or hike the back trails toward the Tonto Rim. A few work in Payson nearby, but most live here to get away from the world.

It’s the threshold between Arizona’s two souls—desert and highland.

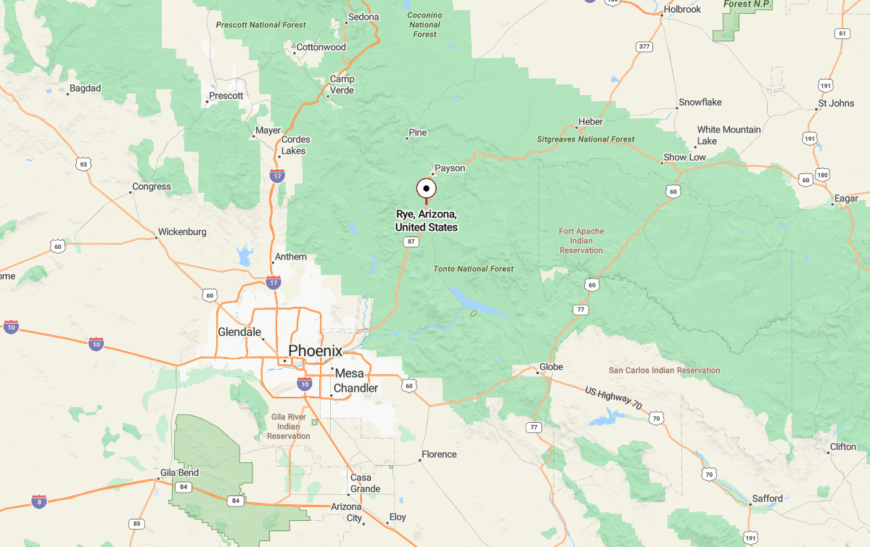

Where is Rye?

Rye lies in northern Gila County, ten miles south of Payson along AZ-87. The road flattens as it enters town, slipping between scrubby hills and creekbeds that catch the morning fog.

Far from interstates and big-box convenience, Rye holds a stillness born of its landscape. It’s the kind of place that feels like a breath you didn’t know you were holding.

15. Bonita

Bonita sprawls gently along a grassy plateau east of Mount Graham, where windmills spin beside barns and mailboxes line the highway without houses in sight. This old ranching community holds fewer than 50 year-round residents.

Cattle drives still roll through in spring, and locals hunt deer or picnic beside Bonita Creek. A few teach or work with the Forest Service, but mostly the land provides—or asks for nothing.

It’s the kind of place where people measure seasons by how tall the grass grows.

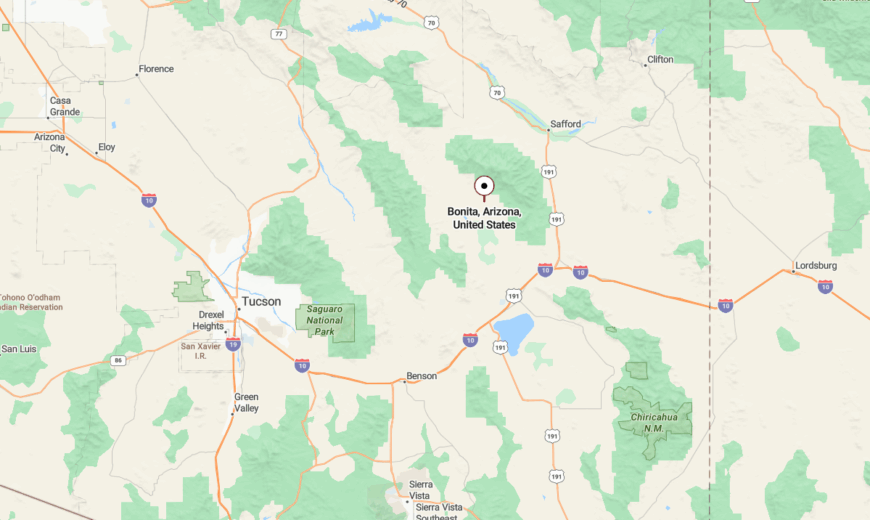

Where is Bonita?

Bonita rests in western Graham County, near the base of Mount Graham, just off State Route 266. You reach it by following a gravel road through ranchland, where barbed wire and cattle crossings outnumber road signs.

Low hills and golden grasslands surround the town like a soft fence. The world seems to pause here—not from remoteness, but from rhythm.

14. Sanders

Time slows in Sanders, where wind-swept plateaus meet stands of piñon and juniper, and the pace of life hums just above stillness. It’s a modest community with deep Navajo roots, scattered homesteads, and a rhythm that hasn’t changed in decades.

There’s no rush here—just quiet mornings, long horizon lines, and the occasional pickup kicking up dust along the dirt shoulders of town. People stop for trading post goods, watch ravens trace thermals, or take the long way toward nearby canyon overlooks.

Sanders doesn’t ask much of you—just that you listen to how quiet the world can be when you let it.

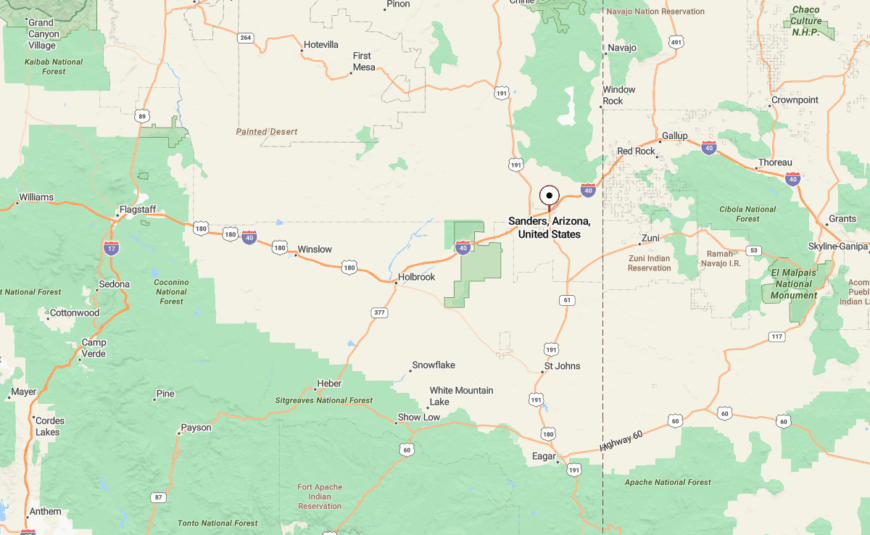

Where is Sanders?

Sanders rests in northeastern Apache County, just off I-40, not far from the New Mexico state line. Though the interstate passes close, the town itself is a quiet offshoot—tucked between red rock mesas and open sky.

The land rolls wide and open, giving the illusion of emptiness—but in truth, Sanders is full of silence, space, and the kind of stillness that stays with you long after you’ve gone.

13. Young

Shielded by the Sierra Ancha Mountains, Young remains one of Arizona’s most remote communities, despite its postcard-worthy beauty. It sits in a hidden valley surrounded by national forest in all directions.

Folks hike into Workman Creek Falls, visit the Pleasant Valley Museum, or fish in nearby Haigler Creek. Logging, ranching, and a few seasonal rentals keep things afloat—but the vibe is pure quietude.

Even the air feels older here.

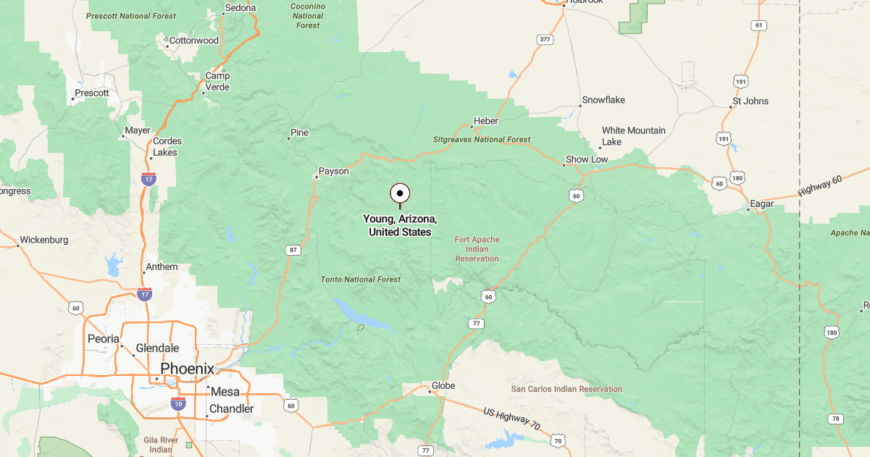

Where is Young?

Young rests in Gila County, 60 miles from Payson via a mix of paved and gravel forest roads. Most visitors come down the narrow AZ-288 or brave the dirt stretch from Globe.

The journey itself is a filter—and few make it through.

12. Fort Apache

Once a military outpost, now a preserved tribal heritage site and tight-knit community, Fort Apache nestles into pine-covered ridges on the reservation that bears its name. Ruins of barracks and officers’ quarters still watch the valley.

People hike the Fort Apache Historic Park, attend cultural events, or work with the White Mountain Apache government. Tourists rarely linger, and those who do often find themselves hushed by the history.

The land remembers everything—and shares only when it chooses.

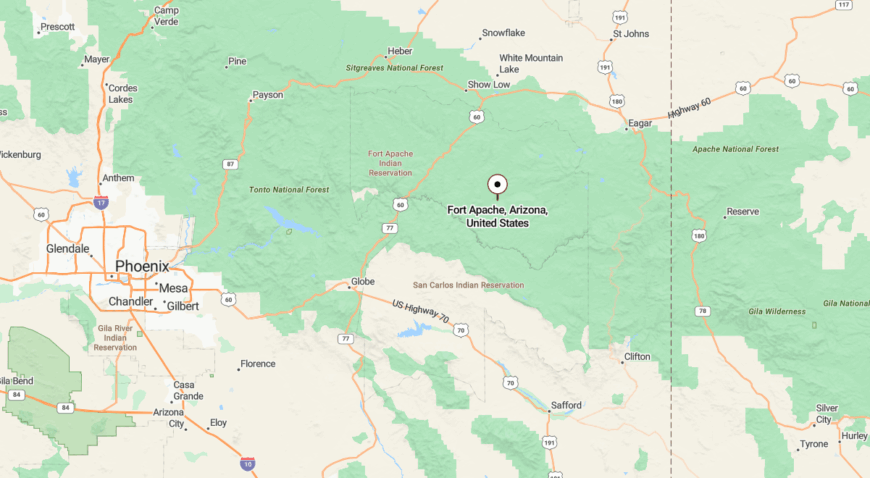

Where is Fort Apache?

Fort Apache is in Navajo County, about 17 miles south of Whiteriver, reached via AZ-73 and a few winding turns past forested plateaus. Roads narrow, pine shadows deepen, and cell service fades.

It feels less like arrival and more like discovery.

11. Christopher Creek

Nestled where ponderosa forest meets canyon, Christopher Creek holds a few hundred residents and a legacy of log cabins, trout streams, and long afternoons with no agenda. Once a logging camp, now a retreat.

Locals hike See Canyon Trail, fish in the creek, or sip coffee at the single diner where elk sometimes linger outside. A few vacation rentals exist, but mostly it’s a community built for quiet.

It’s a world in miniature—cradled by cliffs and conifers.

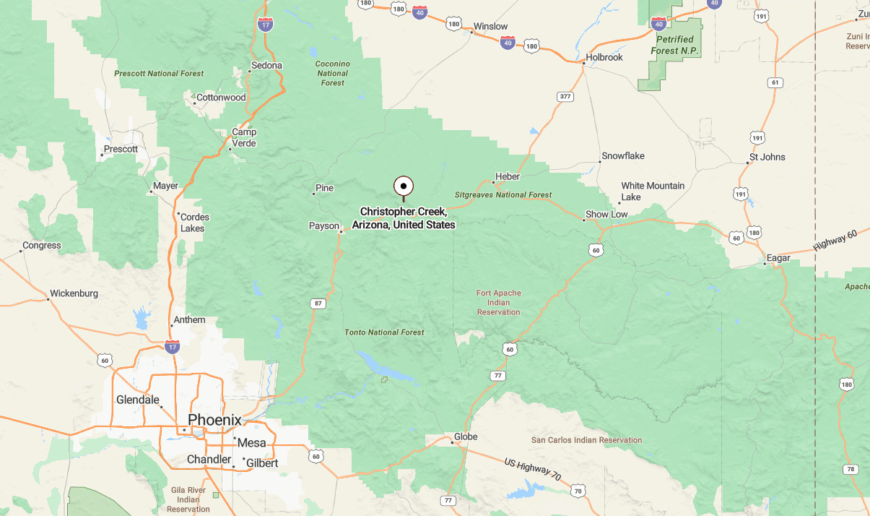

Where is Christopher Creek?

Christopher Creek lies in Gila County, 20 miles east of Payson along AZ-260, tucked just beneath the Mogollon Rim. The two-lane road curves into the canyon and then stops short of anywhere else.

Once you descend into the pines, you don’t feel like climbing out.

10. Greer

Roughly forty year-round residents call Greer home, their cabins sprinkled along the Little Colorado River at 8,500 feet. Visitors and locals spend days fly-fishing for Apache trout, hiking the West Baldy Trail, or carving turns at Sunrise Park Resort a half-hour away.

Hospitality cabins, small outfitters, and a dash of ranching form the hamlet’s modest economic base. Greer feels tucked away because it sits sixteen miles off U.S. 191 on a spur road that dead-ends at the river valley, hemmed in by 11,000-foot peaks and dense spruce.

Cell service flickers, streetlights are absent, and elk often outnumber cars after dusk. Summer crowds never linger long, so quiet returns once the evening breeze rolls down from the White Mountains.

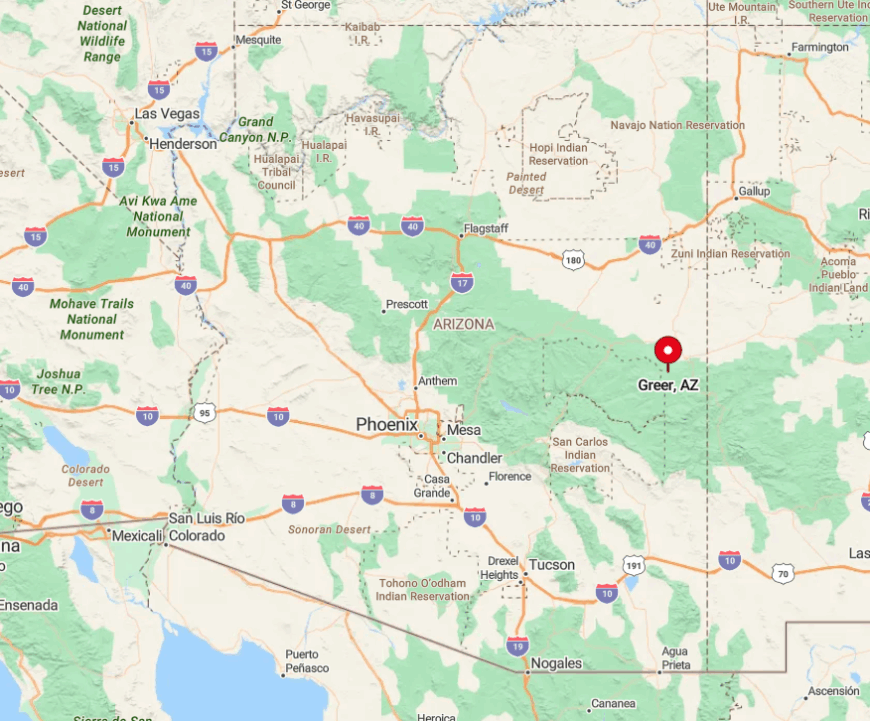

Where is Greer?

Greer lies in Apache County’s White Mountains, accessed by turning south from Eagar-Springerville onto State Route 373. More than three million acres of Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest surround the valley, insulating it from sprawl.

Phoenix drivers face a four-hour trek east on U.S. 60 before dipping south on U.S. 191 and the final winding spur. Winter storms occasionally close the last stretch, underscoring just how removed this alpine hamlet remains.

9. Alpine

Alpine’s roughly 150 residents wake to bugling elk wandering between century-old barns and sprawling ranch parcels. Popular diversions include trolling for trout at nearby Big Lake, riding horses along the Escudilla National Recreation Trail, or browsing the frontier-era artifacts inside the Alpine Community Center.

Cattle ranching and seasonal tourism keep the local economy ticking, though neither has grown enough to dilute the town’s open-range feel. Alpine stays secluded despite sitting at the junction of U.S. 191 and U.S. 180 because those highways carry more scenery seekers than commuters.

Forest on every horizon, thin air at 8,050 feet, and a total absence of stoplights reinforce the sense of distance. Summer thunderstorms roll in fast, and by dark the only glow comes from porch lanterns and Milky Way brilliance.

Where is Alpine?

The village nestles in eastern Apache County, five miles west of the New Mexico border and a stone’s throw from Escudilla Mountain. Albuquerque sits nearly three hours northeast, while Phoenix is over five hours away, giving Alpine a built-in buffer from city bustle.

Drivers reach town on U.S. 180/191, a scenic but curvy route that climbs through ponderosa forests. Beyond those pavement ribbons lie nothing but national-forest ridgelines, making Alpine feel like the last outpost before true wilderness.

8. Nutrioso

Fewer than thirty full-time residents inhabit Nutrioso, where pasture estates spread beneath volcanic buttes at 7,600 feet. Days here revolve around reeling in trout at Nelson Reservoir, spotting osprey that nest along the shoreline, and poking around stone remnants of the 19th-century Nutrioso Fort.

Cattle operations and a sprinkling of vacation-home rentals form the town’s limited commercial scene. The settlement’s isolation is palpable: the nearest grocery aisle sits twenty miles north in Springerville, mail arrives by rural route, and nights stay blissfully dark.

Even summertime traffic rarely exceeds a handful of pickups rumbling down the lone paved road. Nutrioso’s blend of open pasture and pine timber keeps it feeling both airy and sheltered.

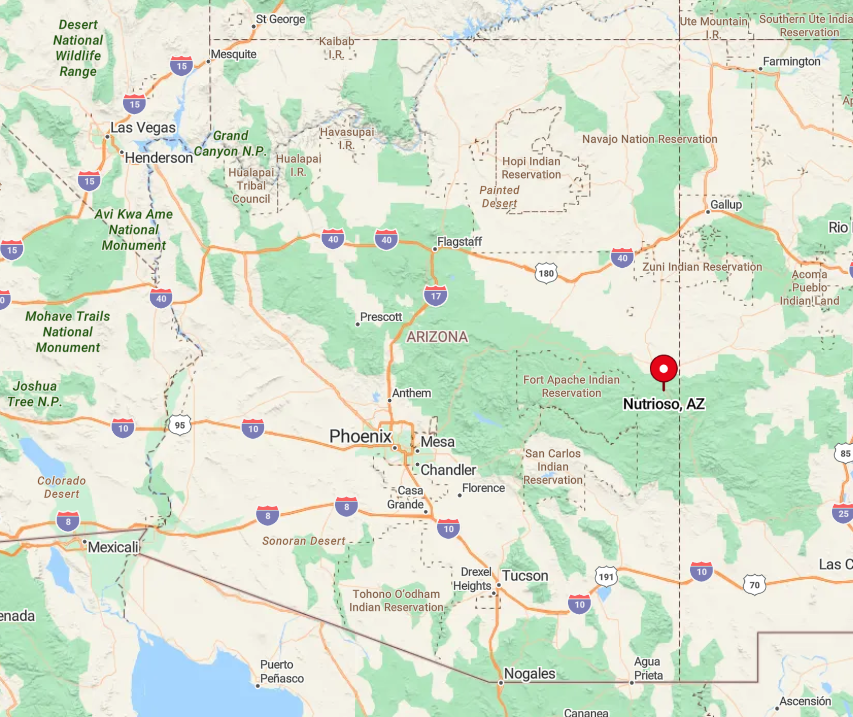

Where is Nutrioso?

Nutrioso straddles U.S. 191 in Apache County, midway between Alpine and Springerville in Arizona’s high-desert transition zone. Though a highway passes through, long stretches of national forest and state trust land on either side deter development.

Most visitors reach the hamlet via U.S. 60, then head south on 191, a route often interrupted by elk crossings. Public transit stops short of the region, so a personal vehicle—or a willing ranch neighbor—is the only way in or out.

7. Blue

Locals say Blue ends where pavement ends, and that pavement stops a good 24 miles before the settlement itself; roughly forty souls stay year-round.

Favorite pastimes include casting dry flies on the crystalline Blue River, trekking into the Blue Range Primitive Area, or hunting for Ancestral Puebloan pottery shards on the mesas (leaving them in place, of course).

Small-scale cattle ranching and Forest Service work supply most incomes, with solar panels and woodstoves powering off-grid homesteads. Seclusion is written into the landscape: ninety percent of surrounding acreage remains federally managed wilderness, and winter storms can make the dirt road impassable for days.

Nights here carry little sound beyond wind in the junipers and distant coyote yips. Even package deliveries wait until locals drive out for supplies.

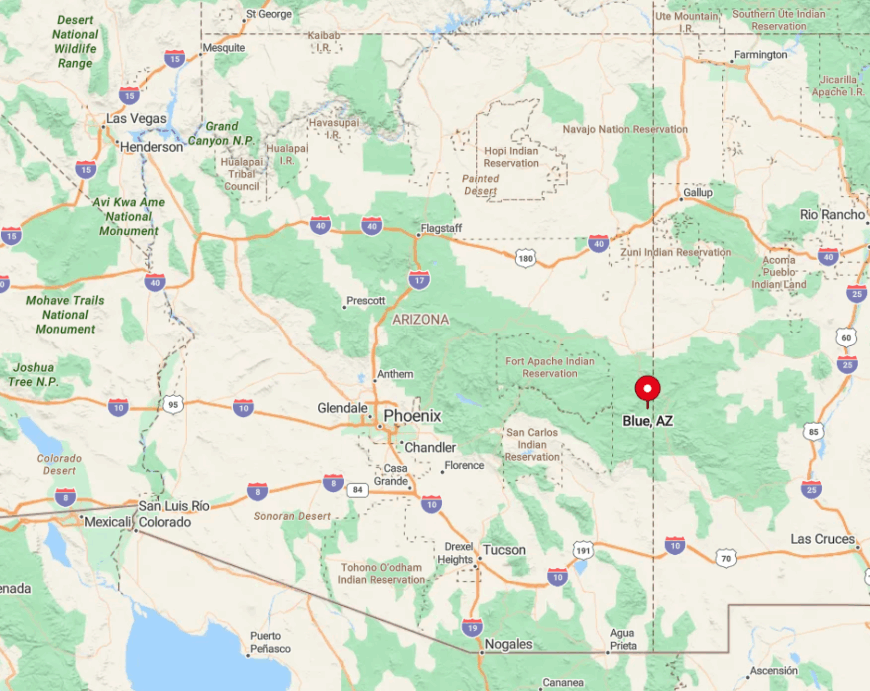

Where is Blue?

Blue occupies a canyon system in extreme eastern Greenlee County, tucked between the Mogollon Mountains and the New Mexico line. Reaching the valley means exiting U.S. 191 at the signed “Blue River” turnoff north of Alpine, then following a graded but sometimes rutted dirt track.

The absence of through-traffic keeps the community hushed; the road dead-ends just south of town. Anyone visiting should check road conditions with the Clifton Ranger District before committing tires to the trek.

6. Aripine

Only eighty-nine residents share Aripine’s grid of three gravel roads, each lined with five-acre ponderosa parcels where porch lights are replaced by starlight. Residents pass evenings watching meteor showers, hiking to the Mogollon Rim’s hidden overlooks, or picnicking beside little-known Potato Lake a few miles west.

Modest ranching and seasonal logging once sustained the area, though today most income arrives from remote work or retirement checks that require no storefronts. Forested buffers and the lack of commercial signage ensure drivers often miss the turnoff entirely.

With no central plaza, gas station, or streetlights, the settlement feels cloaked in quiet long after nearby Show Low’s shops have closed. Coyotes and great horned owls provide the nightly soundtrack.

Where is Aripine?

Aripine sits twelve miles south of Heber-Overgaard in Navajo County, accessed via Forest Road 332 off State Route 260. The Mogollon Rim rises dramatically to the south, cutting off direct passage and confining road access to a handful of forest lanes.

That rugged topography, combined with seasonal snow closures, means travelers plan their arrivals carefully. The nearest full services lie twenty-five minutes away, lending Aripine an enduring sense of remoteness despite its relative closeness to a state highway.

5. Pinedale

Pinedale balances heritage and solitude: fewer than six hundred residents maintain historic pioneer cabins alongside contemporary ranch homes beneath towering ponderosa pines.

Locals hike the Los Burros Trail, wander gravestone-lined clearings at the Pinedale Cemetery, or spin wheels along mountain-bike loops mapped by the community association.

A legacy of timber milling still echoes in small saw shops, though ranching and commuter work in Show Low now dominate paychecks. Despite sitting a dozen miles from that regional hub, Pinedale keeps its hush through heavy timber, absence of nightlife, and a single two-lane road that loops back on itself.

Campfire smoke often replaces traffic exhaust, and deer graze freely between mailboxes. The result is a forest hamlet that feels much farther from town than the odometer claims.

Where is Pinedale?

The village lies in Navajo County, twelve miles west of Show Low off U.S. 260 via Forest Road 130. Dense ponderosa stands cloak the gently rolling terrain, muting highway noise long before drivers reach the first cabin.

Snow can close secondary roads in winter, and summer monsoon downpours sometimes turn forest lanes into red-mud ruts. Those natural gatekeepers ensure Pinedale remains a pocket of peace along the busy Mogollon Corridor.

4. Fort Thomas

Home to about 374 people, Fort Thomas sprawls across irrigated acres where cotton fields meet century-old adobe homes. Residents spend weekends touring the remnants of the 1876 military post, bird-watching along the Gila River corridor, or timing visits to nearby Discovery Park’s stargazing programs in Safford.

Farming—cotton, alfalfa, and chile—anchors the local economy, supplemented by ranch supply shops clustered near the highway. Though U.S. 70 runs past town, Fort Thomas stays low-profile thanks to expansive farmland buffers and the absence of big-box development.

Saguaros stand sentinel on distant hills, while the nearest full grocery selection sits fifteen minutes away. After sunset only tractor headlights and a bright desert sky illuminate the valley.

Where is Fort Thomas?

Fort Thomas lies in Graham County, twenty-two miles west of Safford along U.S. 70. The Gila Mountains rise south of town, and the wide floodplain north leaves little room for subdivision sprawl.

Travelers can reach the community via Interstate 10 through Globe before cutting east, but few detour unless they have business in the fields. That through-traffic bypass keeps the old fort site remarkably tranquil.

3. Klondyke

Only a handful of residents—and considerably more head of cattle—populate Klondyke, an isolated canyon hamlet named during the 1890s gold fever. Daylight hours revolve around exploring creek-carved Aravaipa Canyon, inspecting stone ruins of the old Marks Ranch headquarters, or scanning mesquite flats for Gambel’s quail.

Ranching remains the primary industry, with generators and solar panels powering scattered homesteads that sit miles apart.

Klondyke is secluded because the only approach is a single dirt road branching south from State Route 266; summer flash floods and winter snow alike can make it impassable.

With no commercial center, silence rules once the ranchers’ pickups head home. Nightfall brings an orchestra of wind and distant owl hoots echoing through the canyon walls.

Where is Klondyke?

Klondyke rests in western Graham County, twenty-five miles south of the Safford-Willcox highway corridor. Drivers exit SR 266 near Bonita and follow Klondyke Road, a maintained dirt track crossing washes and open range.

The route dead-ends in town, discouraging pass-through motorists and keeping traffic almost exclusively local. Those who brave the trip are rewarded with startlingly dark skies and a profound sense of being far from modern haste.

2. Eden

Roughly 150 people share Eden’s patchwork of citrus groves, cottonwood corridors, and famed geothermal pools. Residents and visitors alike soak in the historic Eden Hot Springs—once a 19th-century resort—then cool off by kayaking quiet stretches of the Gila River or picking oranges straight from backyard trees.

Small-scale agriculture and the hot-spring guesthouses fuel the local economy, while a scattering of artists maintain workshops in converted barns. Eden remains secluded partly because it sits fifteen miles from the nearest town services and enjoys natural screens of river forest and low mesas that block highway noise.

Traffic lights are nonexistent, and many residences still rely on private wells. Come evening, the scent of citrus blossoms travels farther than any engine hum.

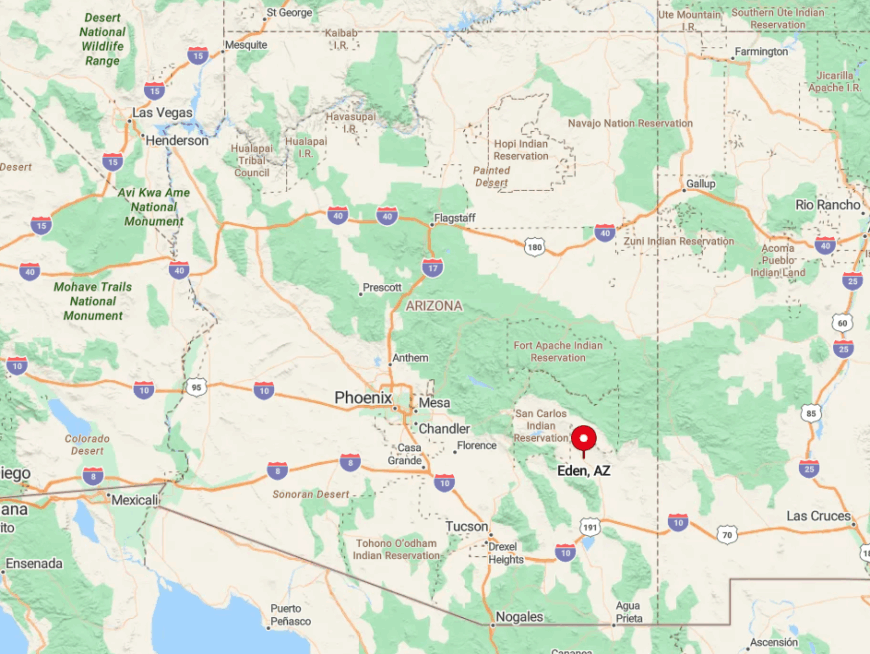

Where is Eden?

The community occupies a verdant bend of the Gila River in central Graham County, reached by turning north off U.S. 70 between Pima and Fort Thomas. Cotton fields give way to tree-lined lanes as the road narrows toward the riverbank.

The lack of a bridge crossing east or west of town keeps Eden off most GPS shortcuts. Travelers aiming for the hot springs find that the final mile shifts to graded dirt, a subtle reminder of the settlement’s persistent sense of remove.

1. York

York claims fewer than twenty full-time residents, their ranch houses scattered across a river-carved valley hidden by chaparral hills. Locals ride all-terrain vehicles to old copper prospects, fish for catfish in the San Francisco River, or wander among century-old stone corrals left by pioneer stockmen.

Modest cow-calf operations and part-time prospecting constitute the closest thing to industry, and mail arrives at a roadside kiosk twice a week. Shielded by rolling hills, absent of traffic lights, and lacking any tourist draw, York enjoys a stillness rarely found in the Southwest today.

Night skyscapes rival nearby Dark Sky Parks thanks to zero commercial illumination. Those who settle here do so for space, silence, and a relationship with land that changes only with rain and calving season.

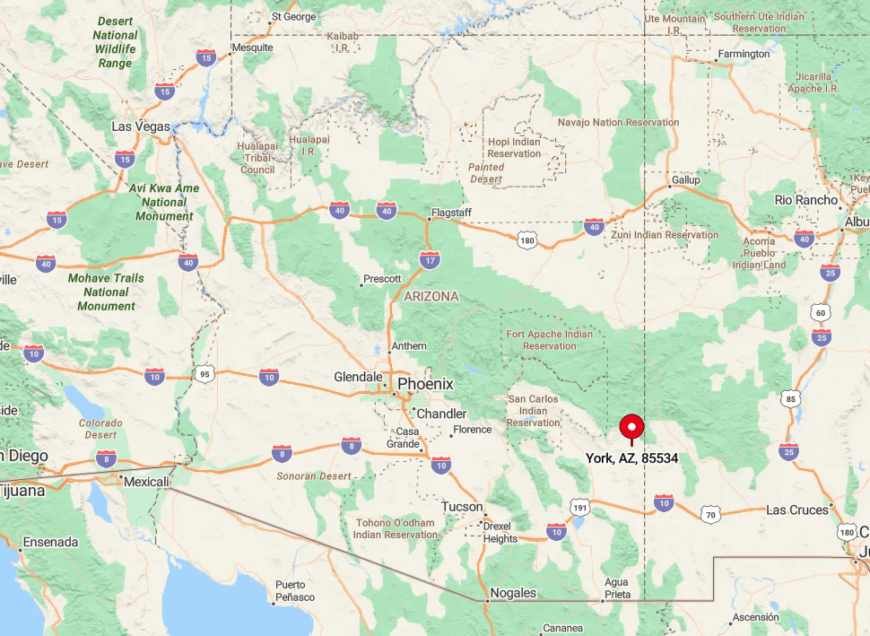

Where is York?

York sits in southeastern Greenlee County, nine miles south of U.S. 70 on graded Country Road 400. The San Francisco River Valley’s high walls block radio and cell signals, deepening the feeling of isolation.

Closest services lie thirty miles east in Clifton, reached by winding along the Gila River and through Morenci’s mine terracing. The absence of a through-route means anyone who reaches York intends to be there—an arrangement the residents seem keen to preserve.