Would you like to save this?

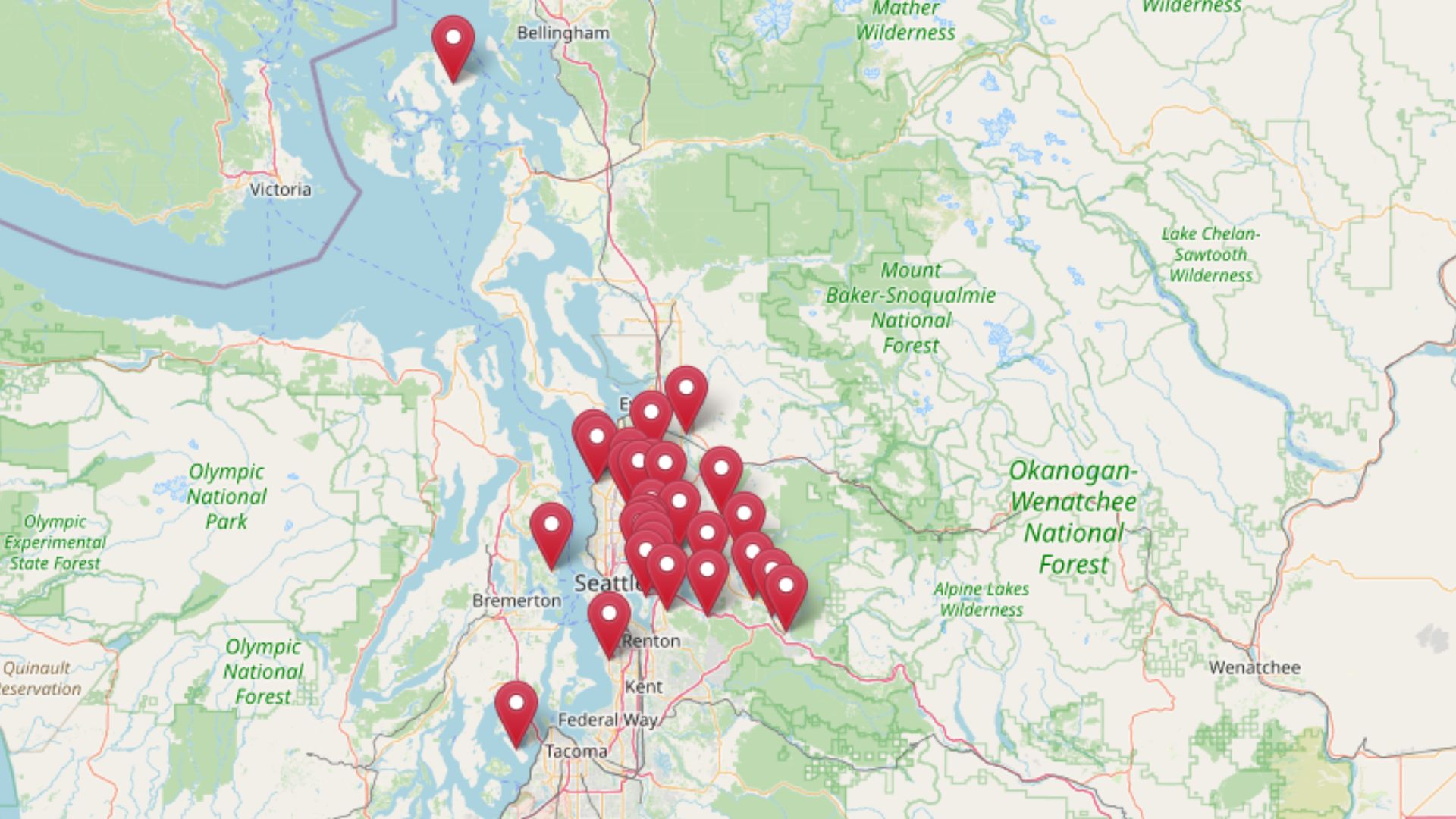

The Pacific Northwest hides coves and peninsulas where conifers lean over saltwater and village life still moves by tide tables. Northwestern Washington in particular is dotted with quiet coastal settlements that feel many leagues from the urban web, even when the crow-flight distance is short.

Our roundup counts down 25 of the most secluded among them, highlighting what residents do for work and play, why development has stayed modest, and how adventurous travelers can find each place.

Expect stories of reef-net fishermen, border quirks, cedar-scented trails, and night skies unspoiled by city glow. These communities prove that solitude and sea air are never completely out of reach; they simply require a willingness to take the slower road or a small ferry.

25. Neah Bay – Where the Road Ends and the Pacific Begins

Neah Bay wears ocean weather like a shawl—mist in the morning, gulls riding the wind, and breakers breathing at the edge of town. Its deep seclusion comes from geography itself: the highway ends here, with the Makah Reservation embraced by sea cliffs and rainforest.

The vibe is elemental and storied—cedar canoes, smokehouses, and the quiet pride of a community shaped by tides. Visit the Makah Museum’s world-class artifacts, walk the Cape Flattery boardwalk to the continent’s edge, beachcomb Shi Shi’s wild sands, or scan for migrating whales at Shipwreck Point.

Fishing, tribal enterprises, and small lodges steady the local economy without chasing crowds. Evenings arrive with the thrum of surf and a sky emptied of city glow. It’s the kind of place that reminds you how quiet the world can be.

Where is Neah Bay?

Tucked into the far northwest corner of Clallam County, Neah Bay sits about 95 miles west of Port Angeles. Reach it via US-101 to SR-112, a cliff-hugging two-lane that slows even confident drivers.

With Olympic National Park and the Strait of Juan de Fuca bracketing the route, there’s no shortcut—only scenery. It’s close enough for a day’s adventure, but far enough to feel like you’ve left everything behind.

24. Joyce – Blackberry Lanes and Strait-Side Sunsets

Joyce strings along the old railroad grade with a one-of-a-kind general store and a handful of weathered porches facing blue water. Its tucked-away feel comes from SR-112’s curves and the forested hills that muffle any notion of haste.

The vibe is friendly and old-timey: blackberry festivals, church potlucks, and tidepool rambles at low tide. Explore Salt Creek Recreation Area’s Tongue Point tide pools, watch sunsets at Crescent Beach, hike the Spruce Railroad Trail, or nurse a milkshake at the counter while summer rain drums the awning.

Logging, park work, and mom-and-pop shops keep the lights on. At night, the strait goes silver and quiet. Joyce is what happens when a highway and a coastline agree to slow you down.

Where is Joyce?

Were You Meant

to Live In?

On the Strait of Juan de Fuca west of Port Angeles, Joyce sits along SR-112 about 16 miles from town. The road pinches between bluffs and water, discouraging heavy traffic.

Detours are few, and most travelers mean to be here. It’s a short map distance with a pleasantly long mood shift.

23. Pysht – Spruce Flats and River Mouth Calm

Pysht is scarcely a cluster of homes where the Pysht River meets the strait, guarded by old-growth spruce and a wide, pebbled shore. Seclusion here is the rule—no main street, no neon, just the slow pulse of tide and wind.

The vibe is spare and salt-washed, with beach grass hissing and eagles drawing lazy circles overhead. Walk the driftwood shore, watch storms roll in from Vancouver Island, cast for surfperch on calm days, or wander forest spurs for mushrooms in fall.

Forestry remains the quiet backbone, with a bit of fishing and seasonal vacation rentals. Even the road seems to whisper as it passes. Pysht feels like the coast telling you a secret and trusting you to keep it.

Where is Pysht?

You’ll find it midway along SR-112 in Clallam County, roughly 40 miles west of Port Angeles. The highway narrows to intimate curves with long stretches of trees and water.

Services are sparse between towns, so the last miles feel especially remote. It’s easy to miss—and that’s part of the magic.

22. Nordland (Marrowstone Island) – Tidelands, Forts, and Soft Light

Home Stratosphere Guide

Your Personality Already Knows

How Your Home Should Feel

113 pages of room-by-room design guidance built around your actual brain, your actual habits, and the way you actually live.

You might be an ISFJ or INFP designer…

You design through feeling — your spaces are personal, comforting, and full of meaning. The guide covers your exact color palettes, room layouts, and the one mistake your type always makes.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ISTJ or INTJ designer…

You crave order, function, and visual calm. The guide shows you how to create spaces that feel both serene and intentional — without ending up sterile.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ENFP or ESTP designer…

You design by instinct and energy. Your home should feel alive. The guide shows you how to channel that into rooms that feel curated, not chaotic.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ENTJ or ESTJ designer…

You value quality, structure, and things done right. The guide gives you the framework to build rooms that feel polished without overthinking every detail.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

Nordland drifts along Marrowstone Island’s eastern shore, where tide flats glimmer and boats bob at their moorings. Seclusion comes from being one island beyond an island: you cross Indian Island first, then slip onto Marrowstone by a small bridge and narrower roads.

The vibe is hushed and wind-polished—historic farmhouses, crab pots stacked by sheds, and gulls skittering over eelgrass. Launch a kayak at Mystery Bay State Park, explore the gun batteries and bluffs at Fort Flagler, sip coffee at the tiny marina store, or beachcomb Oak Bay on a minus tide.

Retirees, park staff, shellfish farms, and artists share the daily rhythm. Sunset pours copper across Admiralty Inlet, and everything goes very still. Nordland is an island within an island where the clock runs on tide time.

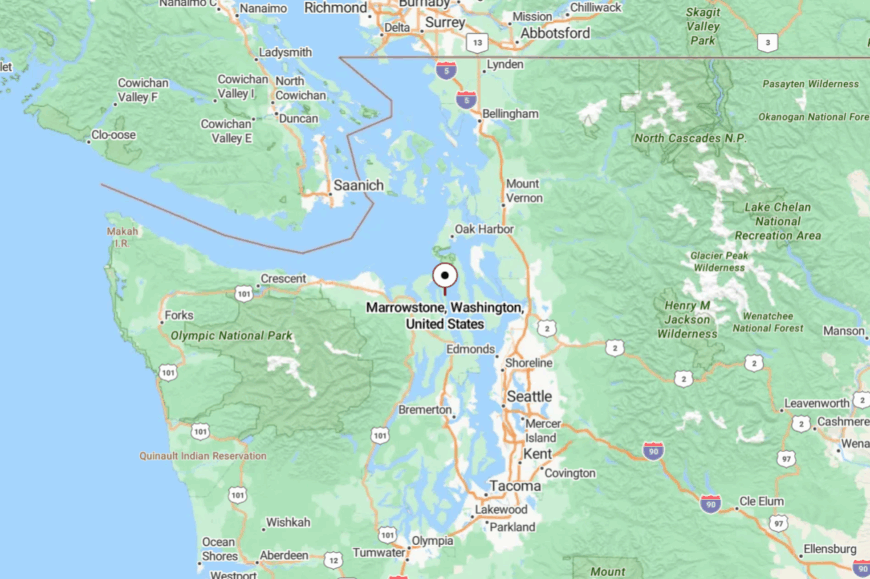

Where is Nordland?

Set in Jefferson County, Nordland lies 12 miles southeast of Port Townsend on Marrowstone Island. Drivers follow SR-116 and local bridges from the Quimper Peninsula to the island’s quiet lanes.

With water on three sides and no commercial strip, traffic melts away quickly. It’s close to a Victorian seaport, yet it feels a world apart.

21. Coyle – The Toandos Peninsula’s Last Turn

Coyle sits at the far end of the Toandos Peninsula, a finger of timber and tide that points into Hood Canal. Its out-there feel is literal: one road in, one road out, and plenty of miles where trees arch over the asphalt.

The vibe is cedar-scented and neighborly—pop-up concerts at the community center, beach walks to find moon snails, and star fields unbothered by streetlights. Paddle Dabob Bay’s glassy mornings, scan tidelands at Broad Spit, picnic under bigleaf maples, or listen to live music at the Coyle concerts on weekend nights.

Shellfish work and remote-friendly jobs support a small year-round community. When the breeze turns and the canal goes mirror-calm, time seems to stop. Coyle is the kind of end-of-the-road that keeps you gladly there.

Where is Coyle?

In Jefferson County, Coyle sits about 18 miles southeast of Quilcene at the tip of the Toandos Peninsula. Take Coyle Road off US-101, then follow miles of two-lane through forest and farms.

With Hood Canal hemming the route, there are no shortcuts back to the highway. It’s close enough to haul groceries, far enough to hear your own footsteps.

20. Brinnon – Elk Meadows and Fjord-Quiet Water

Brinnon leans against the east slope of the Olympics, where river valleys spill into emerald Hood Canal. Seclusion stems from mountains at the back door and saltwater at the front, narrowing travel to a simple ribbon of 101.

The vibe is outdoorsy and unpretentious: elk grazing Dosewallips flats, kayaks slipping into Pleasant Harbor, and smoke from an oyster grill ghosting the evening air. Watch for the resident elk herd at Dosewallips State Park, boat from Pleasant Harbor, hike the Duckabush trail into wilderness, or slurp oysters at waterside stands.

Shellfish, marinas, and trail-minded businesses anchor the week. Nights carry the soft clink of rigging from the marina. Brinnon is a place where the mountains teach the sea to be quiet.

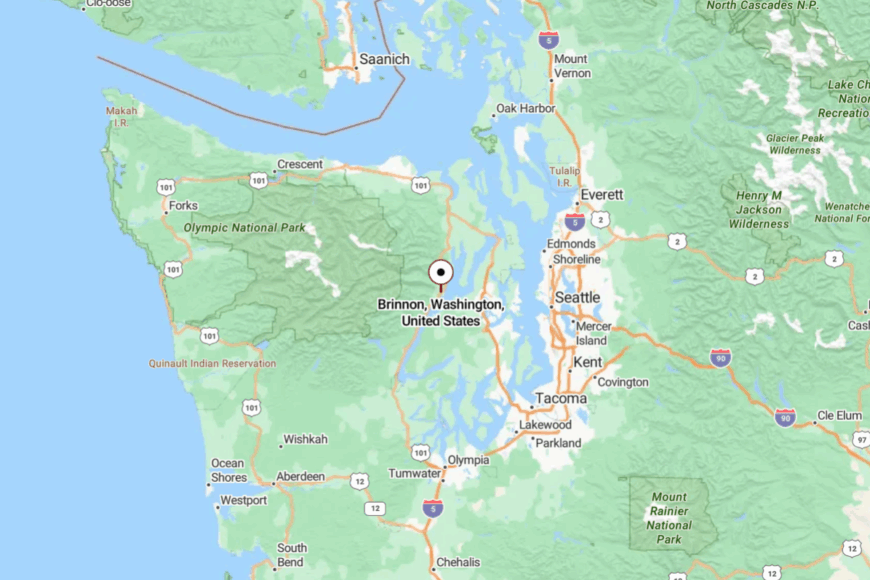

Where is Brinnon?

Along US-101 in Jefferson County, Brinnon sits about 30 miles south of Quilcene and 45 north of Shelton. The canal on one side and steep foothills on the other make 101 the only sensible approach.

Switchbacks and viewpoints slow everyone to the same pace. It’s a drive that trades minutes for calm.

19. Lilliwaup – Oyster Baskets and Rain-Polished Slopes

Lilliwaup is a pocket hamlet on a bend of Hood Canal where tide flats gleam and mountains stare back. Its tucked-away nature comes from the narrow shelf between water and cliff; there’s simply not much room for bustle.

The vibe is briny and content—oyster skiffs putter at dawn, and the evening’s entertainment is sunset over a glassy fjord. Shuck Hama Hama oysters at a picnic table, hike Jefferson Ridge for an eagle’s view, beachcomb the cobbles at low tide, or cast for cutthroat when the water goes calm.

Shellfish aquaculture and seasonal visitors keep lights glowing in windows without changing the volume. After dark, the canal becomes a long mirror. Lilliwaup is the taste of the sea and the hush of the hills in the same breath.

Where is Lilliwaup?

On the west shore of Hood Canal in Mason County, Lilliwaup lies 9 miles south of Hoodsport along US-101. Sheer slopes and shoreline make passing zones scarce and keep traffic light.

Services arrive in small clusters, then vanish back to trees. It’s close to the highway, but it feels like someone turned the sound down.

18. Hansville – Lighthouse at the End of the Road

Hansville stretches toward the tip of the Kitsap Peninsula, where Point No Point Lighthouse keeps easy watch over quiet shallows. Seclusion here is a matter of geography: cul-de-sac lanes, beach spits, and the open reach of Admiralty Inlet.

The vibe is breezy and bird-rich—kite lines scribbling the sky, sandpipers stitching the tideline, and boats idling past on an unhurried course. Walk the lighthouse beach, explore Foulweather Bluff Preserve’s mossy trails, cast for salmon from shore in season, or scan for orcas when the water goes glassy.

Retirees, commuters, and seasonal visitors share the village’s soft rhythm. At dusk, the light blinks and everything else hushes. Hansville is where the map ends in sand and sky.

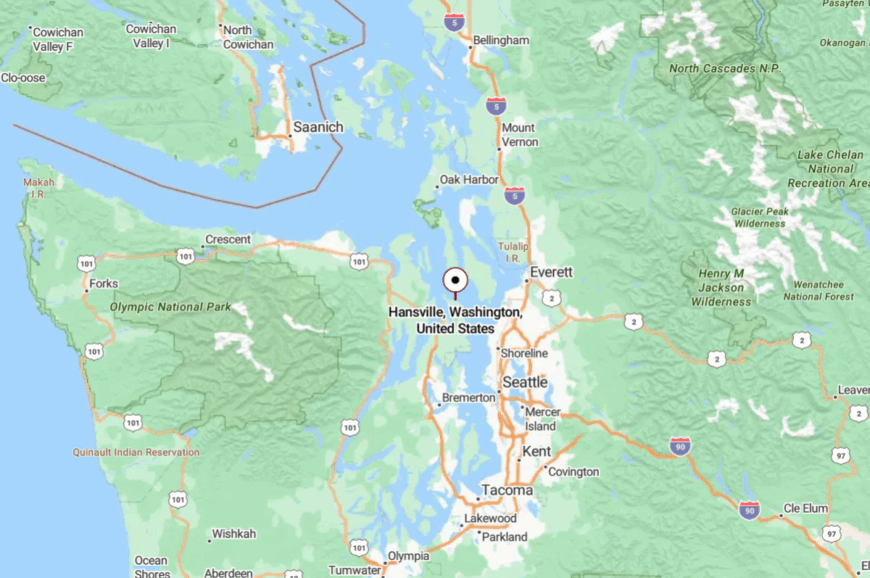

Where is Hansville?

In far north Kitsap County, Hansville sits about 10 miles north of Kingston at the terminus of Hansville Road NE. The approach winds through evergreens and past small lakes before spilling onto beach roads.

With water on three sides, there’s no through route to anywhere else. It’s close to ferries—but emotionally across a strait.

17. Indianola – Long Dock, Short Agenda

Indianola keeps its secrets along Port Madison’s calm water, where a century-old dock reaches into a bay like a pointing finger. Its seclusion is social as much as geographic: one small store, few signs, and roads that prefer neighborhood speed.

The vibe is porch-swing gentle—kids crabbing from the pier, herons stalking eelgrass, and sunsets rinsing the water in rose and gold. Stroll the historic dock, beachcomb for sand dollars, launch a kayak at high tide, or grab a sandwich at the Indianola Country Store and eat it on the steps.

The town hums on local trades, remote work, and a spattering of summer cabins. Nights are the color of old photographs. Indianola is the soft-spoken cousin of the Salish Sea.

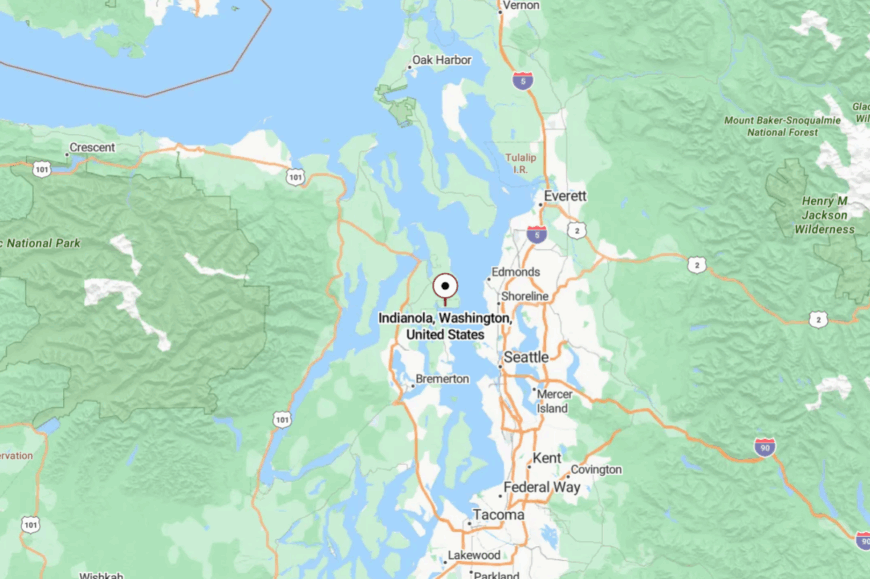

Where is Indianola?

On Port Madison Bay in Kitsap County, Indianola lies 8 miles northeast of Poulsbo. From the Kingston ferry, follow SR-104 and local roads until the forest thins to water and beach grass.

The dock marks the heart; everything else is lanes and trees. It’s near the ferry line but miles from hurry.

16. Greenbank – Whidbey’s Middle Meadow

Would you like to save this?

Greenbank spreads across Whidbey Island’s narrow waist, where old farm fields slope toward two separate bays. Its tucked-away feel comes from being between things—between Penn Cove and Admiralty Inlet, between bigger towns, and beneath wide, quiet skies.

The vibe is pastoral and artsy: pie at the farm café, wind in the grasses, and galleries tucked into barns. Walk the open trails at Greenbank Farm, wander Meerkerk Gardens’ rhododendron paths, birdwatch along Lagoon Point, or sip a cider while the sun melts over Holmes Harbor.

Agriculture, small studios, and commuters share the calendar. Evenings fall soft as wool. Greenbank feels like an island within the island.

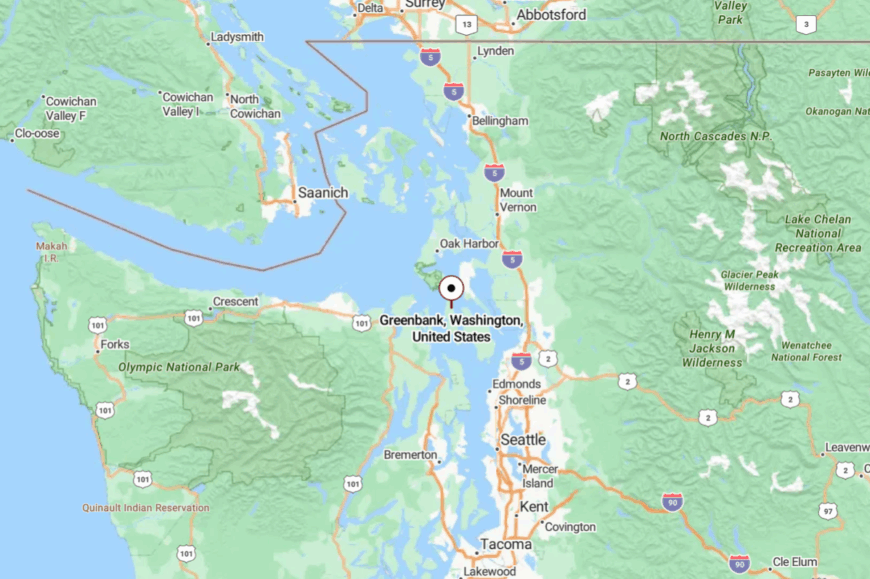

Where is Greenbank?

Mid-island in Island County, Greenbank sits 10 miles south of Coupeville along SR-525. The highway narrows to two lanes and the scenery takes over.

With more pasture than storefronts, there’s little to make you rush. It’s the pause between destinations that becomes the destination.

15. Guemes Island – Short Ferry, Long Quiet

Guemes Island keeps a low profile just across the channel from Anacortes, accessible by a tiny ferry with room for only a handful of cars. Seclusion is enforced by the timetable and the island’s unhurried gravel roads.

The vibe is woodsmoke and salt air—bikes leaning outside the general store, gulls arguing over the dock, and long views toward the Cascades. Hike the Guemes Mountain & Valley trail for a summit meadow, paddle Glass Beach on a windless morning, beachcomb Youngs Park, or linger over chowder at the Guemes Island General Store.

Islanders mix remote work, caretaking, and small trades without turning up the volume. At night, you hear waves and your own thoughts. Guemes is proof that the simplest crossings go the farthest.

Where is Guemes Island?

In Skagit County, Guemes lies a five-minute ferry ride north of Anacortes. The county ferry departs on a short schedule, then leaves you to a modest loop of two-lane and gravel.

With no bridge and few services, every trip is intentional. It’s a speck on the map with a full-size dose of calm.

14. Samish Island – A Road-Linked Island That Still Feels Offshore

Samish Island connects to the mainland by a narrow causeway, but spirit-wise it floats on its own. Seclusion comes from limited parking, no public campgrounds, and a shoreline stitched with private tidelands.

The vibe is tidy and contemplative—herons posted in the shallows, gardens clipped just so, and sunsets pouring between the San Juans. Walk the perimeter lanes, launch a kayak into Padilla Bay, watch snow geese swirl in winter, or sketch the islands from a pocket beach at low tide.

Retirees, artists, and shellfish workers share the quiet. When the tide turns, the whole island seems to breathe. Samish is a bridge away and a world apart.

Where is Samish Island?

On the western edge of Skagit County, Samish sits 20 miles west of Mount Vernon via Bayview-Edison Road and a short causeway. The approach crosses flats where the sky feels larger than the land.

With water hemming three sides, the road ends in a crescent of lanes. It’s easy to reach—and easier to linger.

13. Edison – Art, Bread, and Tideland Light

Edison is a pocket hamlet on the Samish flats where tidewater creases the fields and galleries hide in old storefronts. Seclusion here is visual as much as physical: big sky, low barns, and roads that end in water and birds.

The vibe is artsy-agrarian—fresh loaves cooling at the bakery, oysters on ice, and paintings hung beside farm tools. Browse tiny galleries, eat warm bread, watch eagles hunt over the slough, or pedal the flat backroads to nearby pads of bay.

Farming and food artisans anchor the economy with just enough visitors to pay the bills. Evening light stretches forever across the fields. Edison is a whisper of town with a wide horizon.

Where is Edison?

In Skagit County near the base of Chuckanut Drive, Edison sits 12 miles west of Burlington. Reach it via Bayview-Edison Road, where ditches mirror the sky and tractors set the pace. There’s no rush and nowhere that needs it. It’s close to a scenic byway, yet safely behind the curtain.

12. Olga (Orcas Island) – Cannery Ghosts and Madrona Shade

Olga rests on a sheltered bight where an old cannery once anchored the community and madronas lean crimson into blue water. Its seclusion comes from being a side-bay even by island standards—narrow roads, few signs, and no reason to pass through unless you meant to.

The vibe is handmade and sea-breezy: artists at Orcas Island Artworks, boats nosing at the dock, and gulls heckling crab traps pulled at dawn. Visit the Artworks cooperative, feast on shellfish at nearby Buck Bay, walk Obstruction Pass’s pocket beaches, or watch moonrise over Rosario Strait.

Small farms, studios, and seasonal visitors keep the heartbeat slow. When the tide slips out, time seems to go with it. Olga is the corner of Orcas where island life whispers.

Where is Olga?

On the southeast side of Orcas Island in San Juan County, Olga lies 7 miles from Eastsound via Point Lawrence Road and Olga Road. Lanes narrow, shoulders vanish, and forest presses close.

You’ll come by ferry from Anacortes, then wander the island’s web of two-lane. It’s close to resort hubs but happily off their stage.

11. Deer Harbor (Orcas Island) – Sunset Marina and Turtleback Shadows

Deer Harbor curls around a sheltered inlet where docks glow at golden hour and kayaks slide into glassy water. Its tucked-away feel comes from being pushed to Orcas’s west edge, guarded by Turtleback Mountain and a lacework of shoulderless lanes.

The vibe is maritime and hushed—lines creaking softly, kingfishers strafing the shallows, and evening outings that end with bioluminescence in late summer. Book a whale-watch trip, paddle among pocket islets, hike Turtleback Mountain Preserve, or linger over chowder by the marina.

Charter boats, small inns, and a scattering of craftspeople sustain the harbor economy. When the last skiff idles home, the cove exhales. Deer Harbor is where the day puts itself to bed on the water.

Where is Deer Harbor?

On the west side of Orcas Island, Deer Harbor sits about 8 miles from Eastsound via Crow Valley Road and Deer Harbor Road. The route threads pasture and woods with few straightaways and fewer signs.

Visitors arrive by state ferry to Orcas, then meander to the island’s quiet edge. It’s close enough for an afternoon, far enough to feel like a secret kept by the tide.

10. Sekiu – Tiny Strait-Side Fishing Hamlet

With fewer than 300 residents, Sekiu feels more like a maritime outpost than a town. Anglers launch before dawn from the salt-stained docks to chase salmon and halibut while bald eagles keep watch overhead.

Shore walkers beachcomb for agates then warm up with clam chowder at Olson’s Resort café. Charter fishing, small scale tourism, and a smattering of timber jobs underwrite the local economy.

Rugged ridges block cell signals and the nearest grocery chain is an hour away, so days unfold to the rhythm of tides rather than traffic. That isolation, paired with an ever-present chorus of surf and gulls, grants Sekiu an off-the-map calm prized by those who seek quiet water.

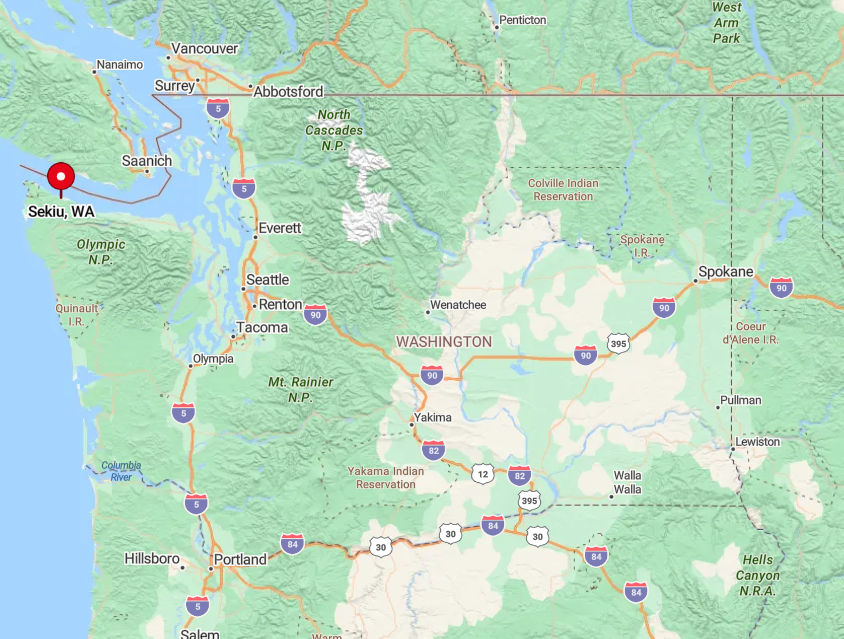

Where is Sekiu?

Sekiu sits on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, about 20 miles west of Port Angeles as the crow flies yet double that by road. State Route 112, a narrow two-lane highway that twists through mossy forest and along cliff edges, is the only land route in or out.

Dense rainforest to the south and open ocean to the north create a natural cul-de-sac that keeps casual passersby away. Drivers generally reach Sekiu in just under two hours from Port Angeles or by looping in from Forks for an even narrower coastal ride.

9. La Push – Rugged Village at the Edge of Olympic Wilds

Roughly 400 people, most of them members of the Quileute Tribe, call La Push home. Towering sea stacks, drift logs the size of buses, and the thump of Pacific swells set the soundtrack for beachcombing, surfing, and storm watching.

Visitors can arrange a tribal guided paddle up the Quillayute River or watch gray whales thread the offshore corridor during migration. Tribal fisheries, small lodge operations, and a modest arts cooperative keep money circulating in the village.

La Push sits literally at the terminus of Highway 110, so there is zero through traffic and nightly silence is punctuated only by crashing waves. Fog shrouds and thick evergreen walls add another layer of privacy that makes the settlement feel like the continent’s true edge.

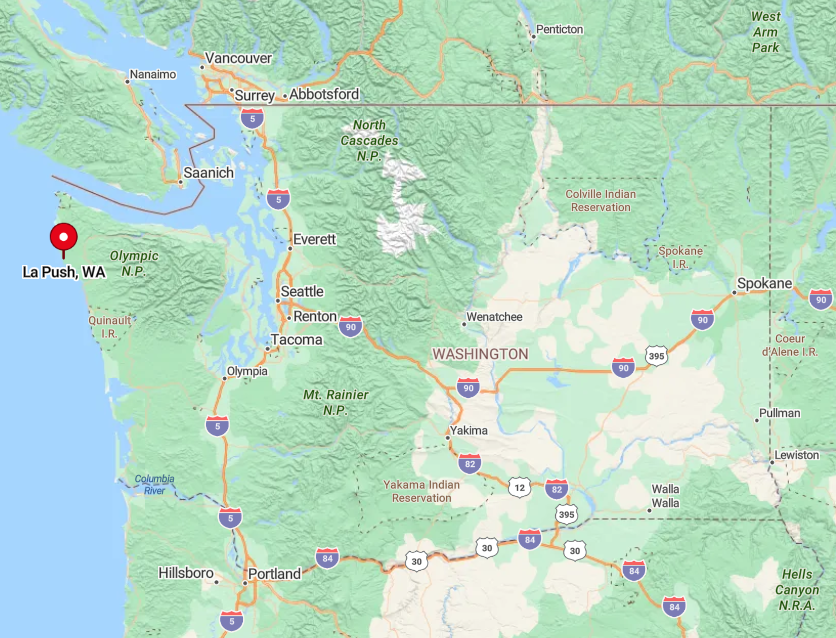

Where is La Push?

The village occupies the river mouth of the Quillayute on Washington’s wild Pacific coast just 15 miles west of Forks. Hemmed in by Olympic National Park on three sides and ocean on the fourth, it is shielded from development of any size.

Access comes via Highway 101 to Forks, then a 14-mile spur that dead-ends at First Beach. That last stretch pins travelers between rainforest and estuary, ensuring only intentional visitors ever arrive.

8. Clallam Bay – Twin Inlet Sanctuary

Clallam Bay shares its name with the twin inlets that cradle a community of about 350 year-round residents. Kayakers glide over glassy tide flats while beachcombers weave among labyrinths of driftwood searching for sea glass.

Commercial fishing, Park Service jobs, and a handful of artist studios anchor the modest local economy.

Sheer distance from urban hubs, scant cell coverage, and shoulder-season road closures make Clallam Bay a coastal sanctuary most tourists miss. Night skies free from light pollution regularly blaze with Milky Way arcs that underscore its remoteness.

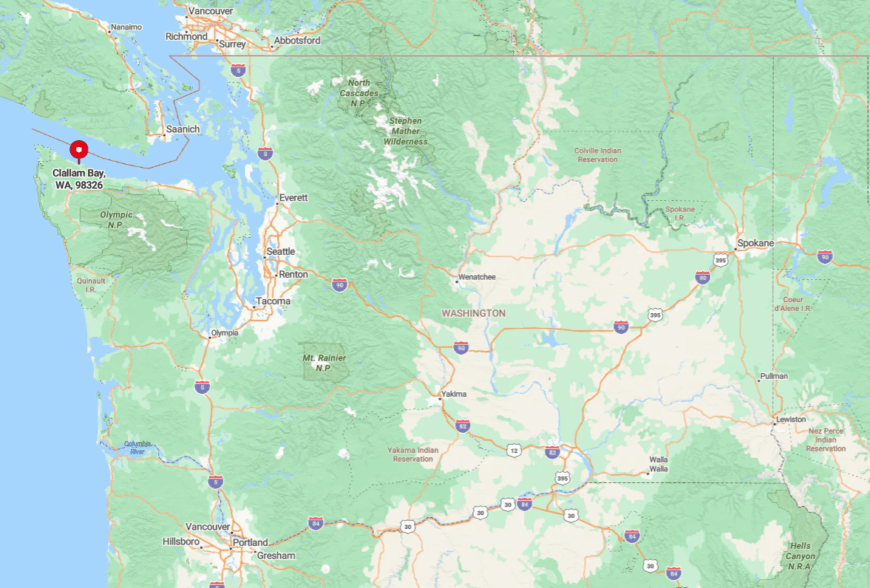

Where is Clallam Bay?

The hamlet sits where the Clallam and Sekiu Rivers spill into separate crescents of the Strait of Juan de Fuca between Neah Bay and Port Angeles. State Route 112 is again the sole ribbon of pavement, curling along capes and coves that slow traffic to sightseeing pace.

Rugged hills to the south prevent any shortcut from Highway 101, forcing visitors to commit to the coastal drive. Those who make the trek from Port Angeles can expect about a 90-minute journey punctuated by frequent photo stops.

7. Lummi Island – Slow-Lane Life a Short Ferry Ride Away

Would you like to save this?

Fewer than 1,000 residents share Lummi Island’s nine scenic square miles. Locals spend free hours cycling quiet gravel roads and hiking to the summit of 1,600-foot Baker Preserve for sunset views.

An acclaimed farm-to-table restaurant, a handful of guesthouses, and artisan pottery studios create seasonal employment without disturbing the hush. Traditional reef-net salmon fishing, small agriculture, and home-based remote work form the economic backbone.

Because the island sits a short boat ride from Gooseberry Point yet lacks a bridge, car traffic remains minimal and audible silence is common. Foggy mornings, pebbled beaches, and no streetlights after midnight reinforce the sense of being far removed from mainland pace.

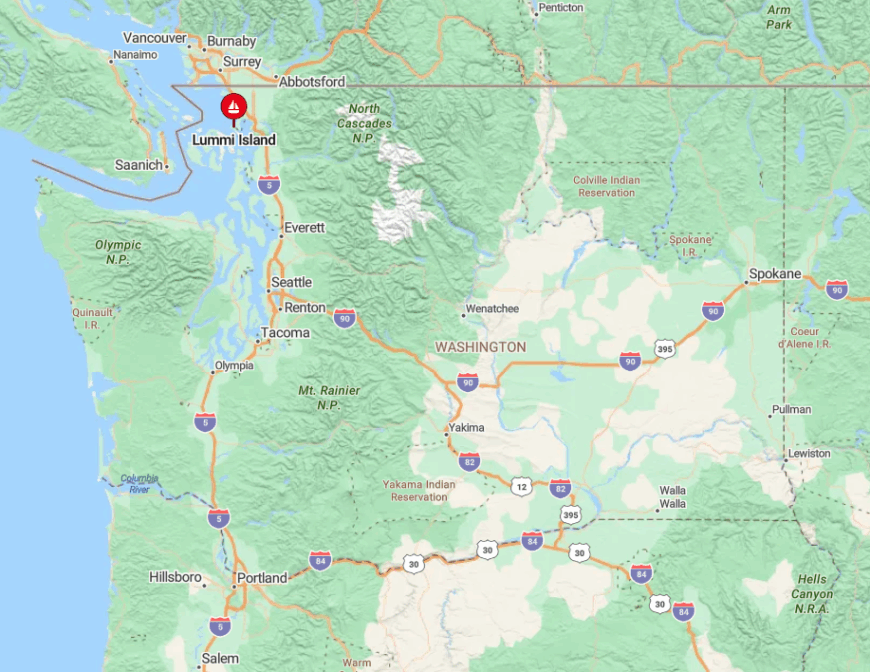

Where is Lummi Island?

The island lies in northern Puget Sound, tucked between Bellingham Bay and the Rosario Strait. Water on every side and a one-boat ferry capable of carrying just 20 vehicles ensure population pressure stays low.

Visitors drive to Gooseberry Point, park in the short queue, then ride the eight-minute Whatcom Chief crossing. Because sailings stop around midnight and strong tidal currents discourage private boating, spontaneity is filtered out, preserving quiet.

6. Doe Bay, Orcas Island – Bohemian Cove Hideout

On the eastern tip of Orcas Island, the Doe Bay community counts only a few dozen full-time residents clustered around a historic resort. Guests greet dawn from steaming cedar hot tubs, then wander to rocky pocket beaches where harbor porpoises often break the glassy surface.

Musicians hold impromptu sets in the café, and hikers lace up for the nearby Obstruction Pass trail’s madrone-lined shoreline. Tourism, wellness retreats, and small organic farms sustain local livelihoods.

The settlement sits well away from Orcas Island’s main village of Eastsound, reached by a network of narrow, shoulderless roads that discourage heavy traffic. With limited cell reception and no street grid, Doe Bay feels like a bohemian hideout suspended outside of clock time.

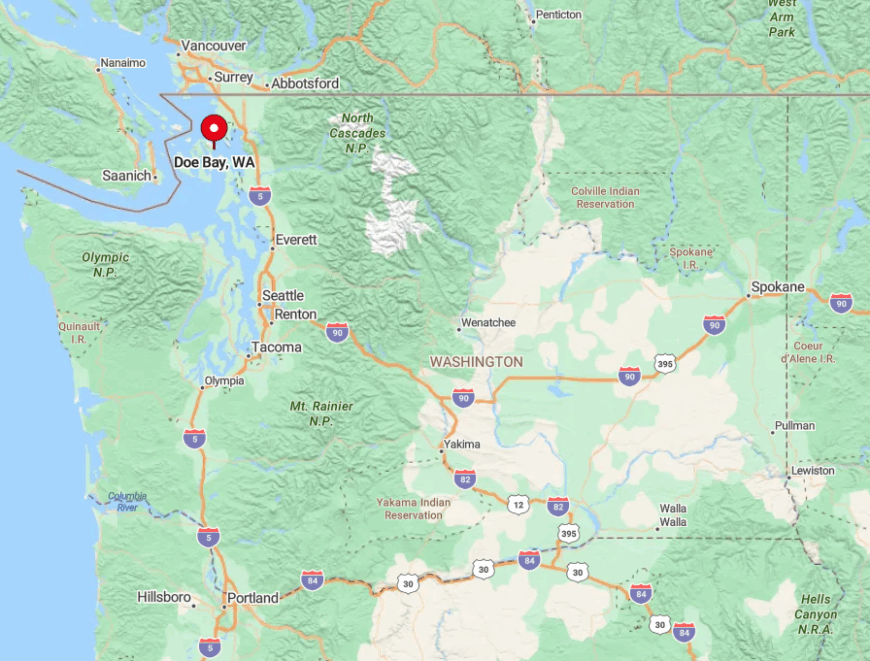

Where is Doe Bay?

Doe Bay occupies a south-facing cove overlooking Rosario Strait in the San Juan archipelago. Water boundaries and protected state-park land on two sides create a pocket of quiet within an already quiet island.

Travelers catch the Washington State Ferry from Anacortes to Orcas Landing, then drive 11 winding miles across forest and pasture to reach the bay. Misjudging the sparse ferry schedule often means an unplanned night on the mainland, a logistical quirk that naturally limits crowds.

5. Blind Bay, Shaw Island – Ferry Stop Frozen in Time

Shaw Island’s Blind Bay hosts about 250 residents who share a single post office, library, and satisfying absence of traffic lights. Kayaks often outnumber cars, and favorite pastimes include spotting marbled murrelets from the dock or paddling to nearby Yellow Island’s wildflower meadows.

The island’s historic Sisters’ Farm and a small county park offer picnic grounds where otters patrol the shoreline. Limited seasonal tourism, shellfish harvesting, and the island’s tiny school provide employment opportunities.

With no lodging chains, minimal retail, and ferry service that skips many sailings, Blind Bay preserves a bygone pace. Even summer nights are quiet enough to hear the slap of salmon tails under the pier’s wooden planks.

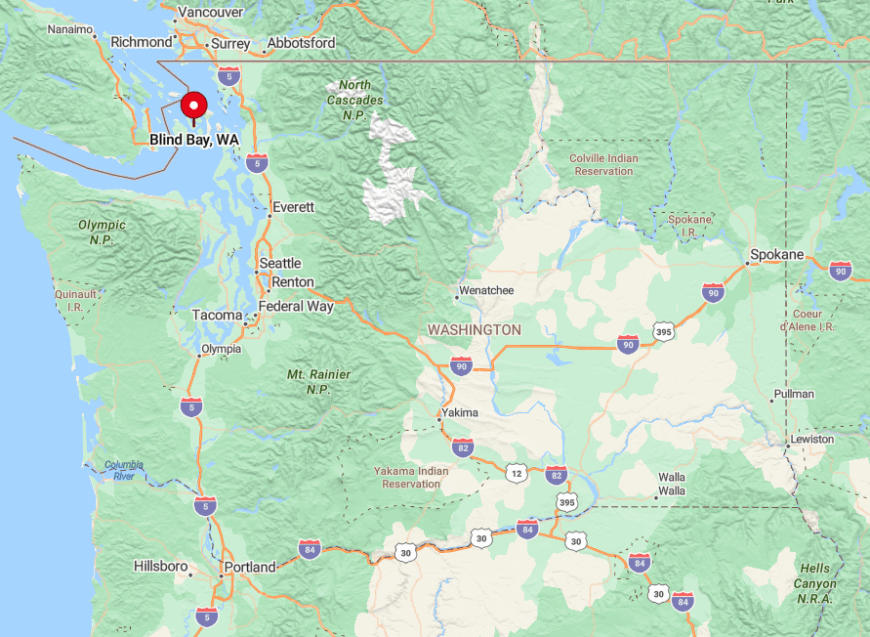

Where is Blind Bay?

The protected anchorage sits on the north side of Shaw Island, midway between Orcas and Lopez Islands in the San Juans. Its horseshoe shape shelters boats from the prevailing westerlies, adding to the oasis feel.

Getting there requires boarding a ferry from Anacortes that sometimes detours through multiple islands before reaching Shaw’s modest landing. Once ashore, visitors rely on a two-lane road system totaling only a handful of miles, so serenity more than sightseeing becomes the itinerary.

4. Hoodsport – Hood Canal’s Forest-Framed Secret

Roughly 375 people reside in Hoodsport, a snug village on the west shore of Hood Canal. Scuba divers slip into teal water at Sund Rock Marine Preserve while hikers tackle the Staircase entrance of Olympic National Park just up the road.

The town hosts tasting rooms for a local winery and distillery, plus a Saturday market featuring smoked salmon and forest-foraged mushrooms. Timber harvesting, outdoor recreation services, and shellfish aquaculture form the economic triad.

Shielded by the steep Olympic foothills and sandwiched against a narrow ribbon of water, Hoodsport sees little through traffic besides Highway 101 day-trippers. Dark evergreen slopes and the deep fjord-like canal bounce sound away, leaving evenings still enough to hear mountain goats clatter on distant cliffs.

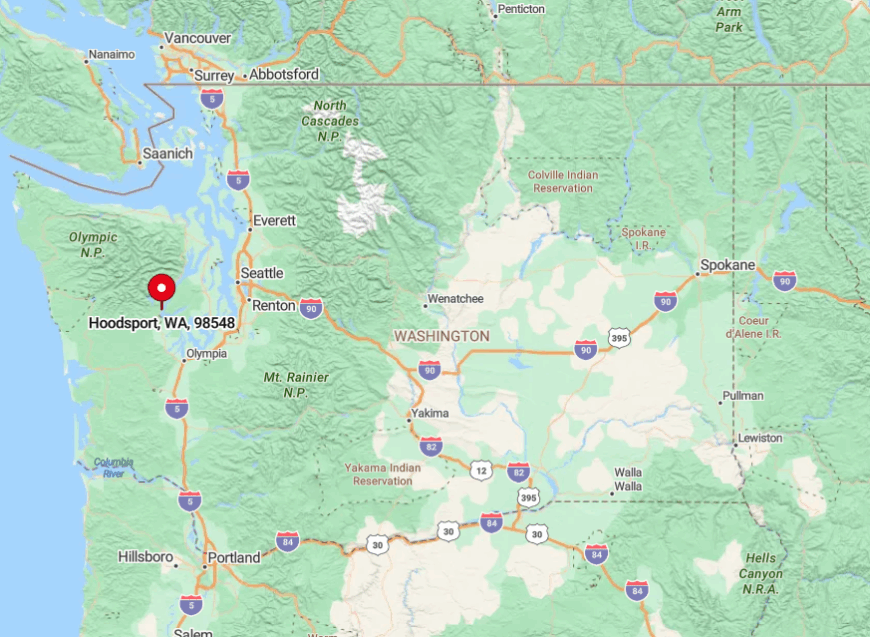

Where is Hoodsport?

Hoodsport is about 90 miles from Port Angeles on the east side of Olympic Peninsula. The Olympic Mountains block any east-west cutoffs, so Highway 101 is the only reliable land route.

Seattle residents must circle through Tacoma then north along rural shoreline, a drive of about two hours that naturally limits weekend crowds.

3. Point Roberts – U.S. Enclave at the World’s Edge

Point Roberts boasts a year-round population just above 1,100 spread over five square miles of low bluffs and pebble beaches. Residents beachcomb for sea glass near Lighthouse Marine Park, kite surf in Boundary Bay’s steady winds, and cheer sunset over Gulf Islands that lie on the horizon.

Small marinas, border duty-free shops, and vacation rentals sustain the economy. Geography makes the community a curiosity because it can only be reached by land through Canada.

This international quirk means most casual American tourists never bother with the double border crossing, leaving beaches strikingly empty even in summer.

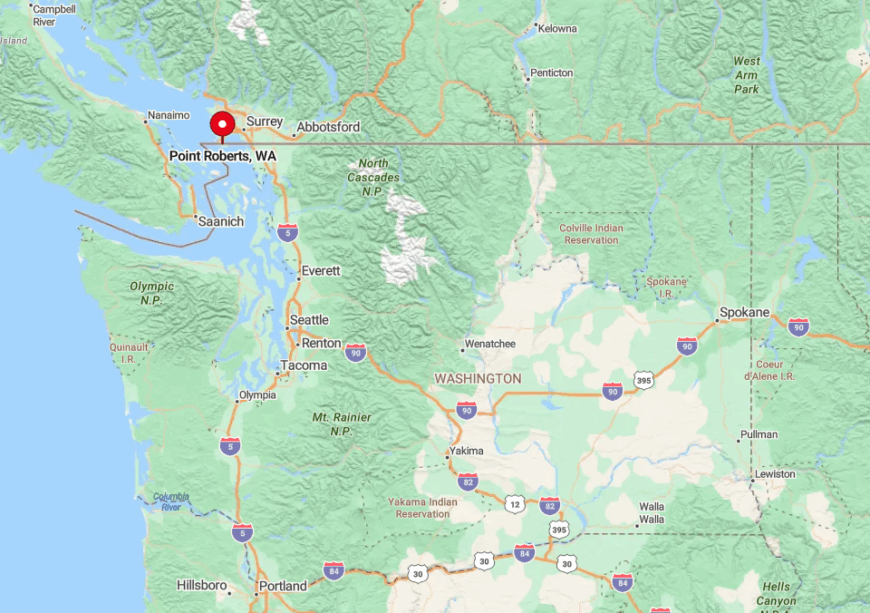

Where is Point Roberts?

The peninsula projects south from Tsawwassen, British Columbia, but falls below the 49th parallel, making it United States territory. Surrounded by water on three sides and a foreign country on the fourth, it functions almost like an island.

Drivers from Washington must cross into Canada at Blaine, travel 25 miles through suburban Vancouver, then re-enter the US at the Point Roberts checkpoint. The only alternative is to charter a boat or small plane from Bellingham, both of which reinforce the out-there vibe.

2. Quilcene – Tide Flats and Oyster Beds Beneath the Olympics

About 600 residents live along Quilcene Bay where tidal estuaries meet snow-fed rivers draining the Olympic Mountains. Visitors shuck briny Quilcene oysters at waterside picnic tables, paddleboard across mirror-calm tide flats, and hike the Mount Townsend trail for vistas of both sea and peaks.

Shellfish farming, heritage dairy operations, and boutique cedar woodworking support the community. The bay’s broad mudflats and surrounding protected forests discourage large-scale development.

Limited cell coverage and just a handful of guest rooms keep nightlife to hooting owls and distant coyote calls. For many Puget Sound residents, Quilcene is a place noticed only on a map, adding to its secret feel.

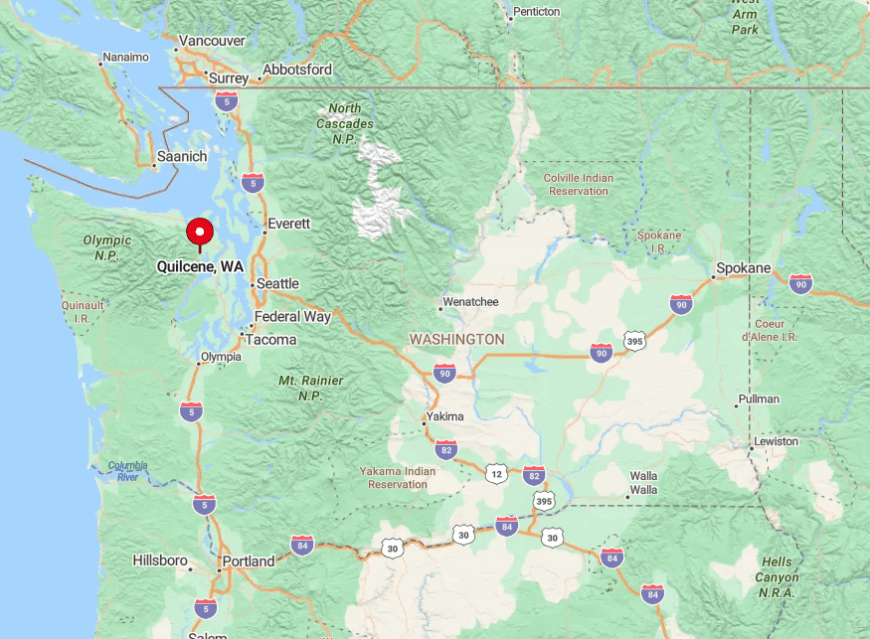

Where is Quilcene?

Quilcene sits on the west shore of Hood Canal near the foot of Dabob Bay in Jefferson County. State Route 101 winds along the shoreline like a ribbon but lacks any major junctions within 30 miles, hemming the town into a quiet corner.

From Seattle, travelers either ferry to Bainbridge Island then drive northwest or loop south through Tacoma, both routes taking around two hours. The absence of commercial bus routes means personal vehicles or bicycles are the only realistic ways to arrive, a hurdle that naturally filters visitor numbers.

1. Seabeck – Historic Mill Town Turned Quiet Retreat

Seabeck, once a bustling mill site, now hosts roughly 1,200 residents spread along spacious one-acre parcels by Hood Canal. Herons stalk wetlands where sawmills once stood, kayakers glide past century-old wharf pilings, and families picnic at Scenic Beach State Park with Mount Rainier looming across the water.

A scattering of art studios, the historic Seabeck General Store, and residential construction comprise the local economy. Encircling forested hills and lack of a town center street grid preserve a hush more typical of the 1890s than modern Kitsap County.

Seattle’s skyline is only 18 air miles east yet multiple layers of water and forest make it feel light years away. Starlit nights, punctuated by owl hoots and the occasional ferry horn far off, reinforce the town’s retreat-like character.

Where is Seabeck?

Seabeck sits on the Kitsap Peninsula’s western edge across Hood Canal from the Olympic Range. A bridge crossing or a ferry ride followed by winding back roads are required for anyone coming from Seattle or Tacoma which slows spontaneous travel.

Public transit reaches nearby Silverdale but does not continue the final 10 miles, so visitors must drive or cycle to reach the waterfront. The resulting detour around bays and inlets acts as a natural moat that keeps Seabeck pleasantly secluded.