Would you like to save this?

Ohio’s landscape hides more than forests, lakes, and farms. Tucked into its hills and valleys are the ghosts of once-thriving communities; places that rose on coal, steel, canals, or pottery, only to fall into ruin. But “ghost town” doesn’t mean just one thing.

In Ohio, these vanished places fall into three haunting categories:

- True Ruins – towns completely gone, where only tunnels, cemeteries, or ruins whisper of the past.

- Shrunken but Still Alive – communities clinging to life with just a handful of residents left.

- Still Populated but Derelict – towns and cities that technically live on, but are shells of their former selves.

Here are twenty towns that tell the story of these towns’ spectacular rise and decline, laid out in those three shades of disappearance.

Category One: True Ruins (Ghost Towns)

20. Ai (Fulton County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Ai was barely a town at all — more a crossroads village in Fulton County. A few farmhouses and a post office clustered at the junction of wagon roads.

Why it went bust

It never grew beyond a handful of buildings. When better roads and rail bypassed the settlement, the tiny community simply dissolved.

Current status?

Ai survives only as a curiosity: Ohio’s shortest-named town, now just a dot on old maps with no physical trace left.

19. Moonville (Vinton County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Moonville grew around coal seams and the Marietta & Cincinnati Railroad in the mid-1800s. Miners, rail workers, and their families carved out a tiny settlement in the woods.

Why it went bust

By the early 1900s, the coal ran out, and trains stopped coming. By 1947, Moonville was abandoned.

Current status?

Nothing remains but stone foundations, a small cemetery, and the famously eerie Moonville Tunnel — now the centerpiece of local ghost stories.

18. San Toy (Perry County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Built by the Sunday Creek Coal Company, San Toy was a bustling company town with nearly a thousand residents in the 1920s.

Why it went bust

The Great Depression, declining coal demand, and fires wrecked the community. By 1931, the remaining residents voted to abandon the town entirely.

Current status?

Only foundations and crumbling roads remain deep in Perry County’s forests.

17. Providence (Lucas County)

Were You Meant

to Live In?

How it became a rich, thriving town?

This canal town thrived in the 1830s and 1840s, a stop along the Miami and Erie Canal. Shops, taverns, and trade buzzed along the Maumee River.

Why it went bust

Disaster struck: a fire in 1846 and cholera in 1854 gutted the population.

Current status?

Today, Providence survives only as part of a Metropark, with canal locks and buildings preserved like a stage set of another era.

16. Fallsville (Highland County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Settled in the 1820s, it grew around a grist mill that served nearby farmers.

Why it went bust

The railroad passed it by, and without commerce, the town withered. The last resident died in 1893.

Current status?

A few foundations and an old water tank remain. The town lives on mostly in ghost stories whispered at night.

15. Boston Mills (Summit County, aka “Helltown”)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

This canal town was busy in the 1800s, later attracting paper mills and settlers.

Why it went bust

In the 1970s, the federal government bought the land to form Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Homes were seized and demolished.

Current status?

Boston Mills is gone, remembered only through eerie legends of “Helltown.”

Category Two: Shrunken but Still Alive

14. Rendville (Perry County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Founded in the 1870s as a coal mining town, Rendville became famous as a predominantly African-American community with a mayor, postmaster, and strong civic life.

Why it went bust

The collapse of coal mining drained jobs and population.

Current status?

Today, fewer than 40 people remain, but Rendville is remembered as a place of Black history and resilience.

13. Shawnee (Perry County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Founded in the 1870s as part of Ohio’s Hocking Valley coal boom, Shawnee filled with miners, saloons, and ornate brick buildings that still line Main Street. It was bustling, with parades and opera houses.

Why it went bust

The coal seams dwindled, and by the mid-1900s the mines shut down. Jobs disappeared, and most families left for larger cities.

Current status?

Today only a few hundred residents remain, but Shawnee’s grand buildings still stand like empty shells, giving it the eerie feel of a town frozen in time. Preservationists are fighting to save its historic downtown.

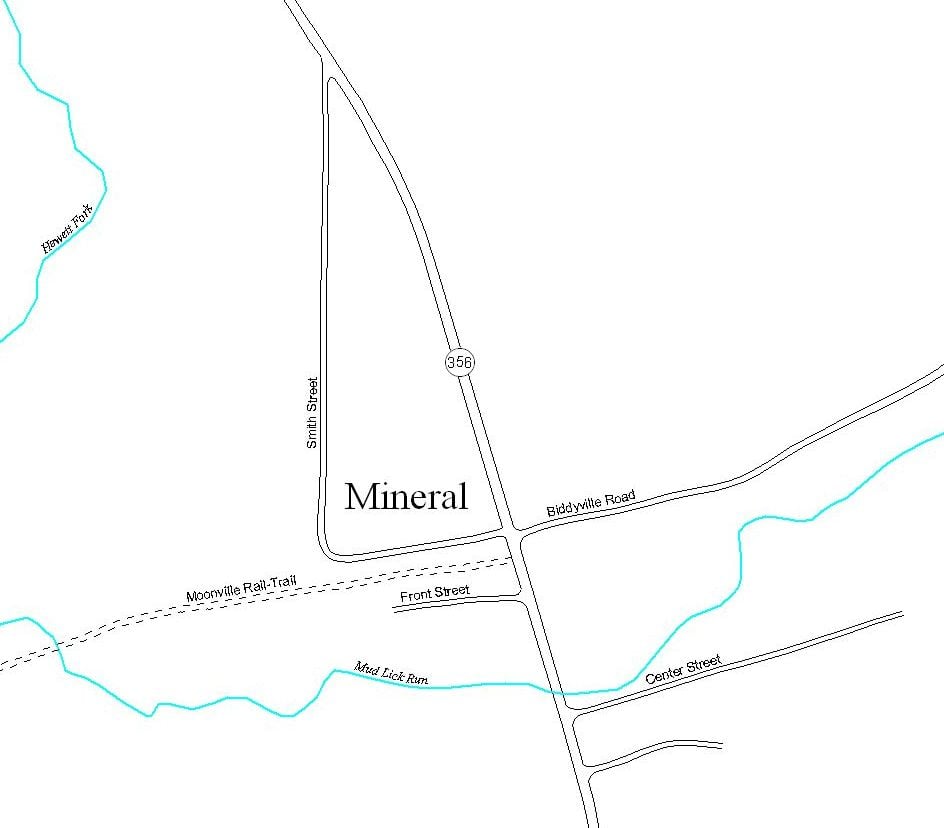

12. Mineral (Athens County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Born as a coal town in the late 1800s, Mineral grew around mines and the railroad that hauled black gold from southeastern Ohio.

Why it went bust

As coal demand declined and the mines closed, the lifeblood of the community was cut off.

Current status?

A handful of houses remain, scattered along backroads, but the sense of a once-busy town has vanished. It’s now more of a “wide spot in the road” than a community.

11. Utopia (Clermont County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Founded in 1844 by followers of French utopian philosopher Charles Fourier, Utopia was meant to be a communal society along the Ohio River. Later, spiritualist groups moved in, building a church and houses. For a time, it thrived on farming, trade, and its unusual communal experiment.

Why it went bust

The community suffered floods, financial troubles, and ideological fractures. The Ohio River repeatedly swallowed homes, and the utopian dream dissolved under harsh realities.

Current status?

Today, only a handful of houses remain along Utopia Road. It’s no longer a communal village, but a sleepy riverside hamlet with a ghostly reputation. The name survives as a haunting reminder of lofty ideals that nature — and history — washed away.

10. Philo (Muskingum County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Philo rose in the late 19th century as a manufacturing and power hub on the Muskingum River. It was home to the Muskingum Power Plant — one of the first large-scale coal-fired power stations in the U.S. — and supported nearby coal mining and river trade. The town flourished around industry and steady jobs.

Why it went bust

As the coal industry declined and the power plant shut down (officially decommissioned in 2015), Philo lost its economic engine. Younger generations left for larger cities, and businesses shuttered.

Current status?

Philo still exists with just over 700 residents, but its past grandeur is gone. It feels more like a ghost of itself, with remnants of the power plant looming over a quiet river town that once dreamed big.

9. Cheshire (Gallia County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Cheshire was a small river town that grew with the Gavin coal plant nearby.

Why it went bust

In 2002, pollution from the plant led the utility company to buy out and demolish most of the town.

Current status?

A few homes remain on the outskirts, but the heart of Cheshire is gone.

Category Three: Still Populated but Derelict

8. East Liverpool (Columbiana County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Known as the “Pottery Capital of the World,” East Liverpool was once home to over 300 pottery companies, booming with wealth.

Why it went bust

Globalization and foreign competition gutted the pottery industry, and jobs vanished.

Current status?

More than 10,000 people still live there, but storefronts sit empty, and poverty shadows the city.

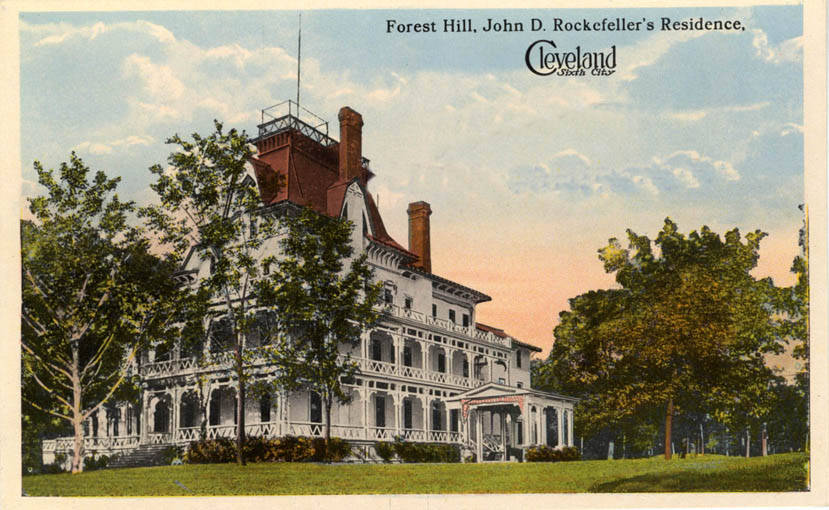

7. East Cleveland (Cuyahoga County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

A wealthy suburb of Cleveland, East Cleveland once dazzled with mansions, tree-lined boulevards, and cultural prestige.

Why it went bust

Deindustrialization, white flight, and political corruption hollowed it out in the mid-20th century.

Current status?

People still live there, but vast sections are abandoned. It is often cited as one of Ohio’s most blighted cities.

6. Mingo Junction (Jefferson County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Steel built Mingo Junction. Its mills employed thousands and shaped the town’s identity.

Why it went bust

The steel industry collapsed in the late 20th century. Jobs evaporated, and families left.

Current status?

Once a vibrant town, it now limps along with a fraction of its former population.

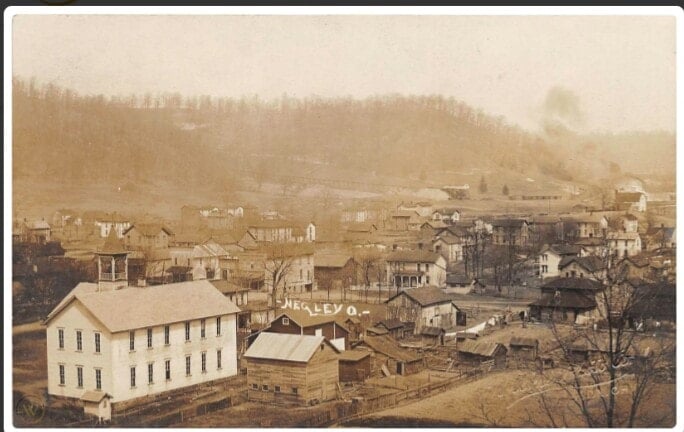

5. Negley (Columbiana County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Negley was a small coal-mining community, humming with railroads and commerce.

Why it went bust

The mines closed, and the small economy that supported daily life went with them.

Current status?

A few hundred people remain, but Negley feels hollow, dotted with abandoned houses and fading memories.

4. Youngstown (Mahoning County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Youngstown was once a titan of American steel, part of the Mahoning Valley’s industrial might. Immigrant families flocked here, and the city thrived with theaters, neighborhoods, and steady jobs.

Why it went bust

The collapse of steel in the 1970s–1980s devastated Youngstown. Tens of thousands of jobs vanished almost overnight.

Current status?

Youngstown still has around 60,000 residents, but vast sections of the city are abandoned — entire neighborhoods of empty houses and factories. It’s a haunting case of a city alive but hollowed out.

3. Lorain (Lorain County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Lorain was another steel city, home to the massive Lorain Works steel mill and shipbuilding on Lake Erie. Immigrants from Eastern Europe and Latin America filled its neighborhoods.

Why it went bust

Deindustrialization gutted Lorain. The steel mill scaled back, shipyards closed, and families moved away.

Current status?

Today Lorain has around 60,000 people, but its downtown and lakefront carry the scars of abandonment — closed factories, empty homes, and high poverty.

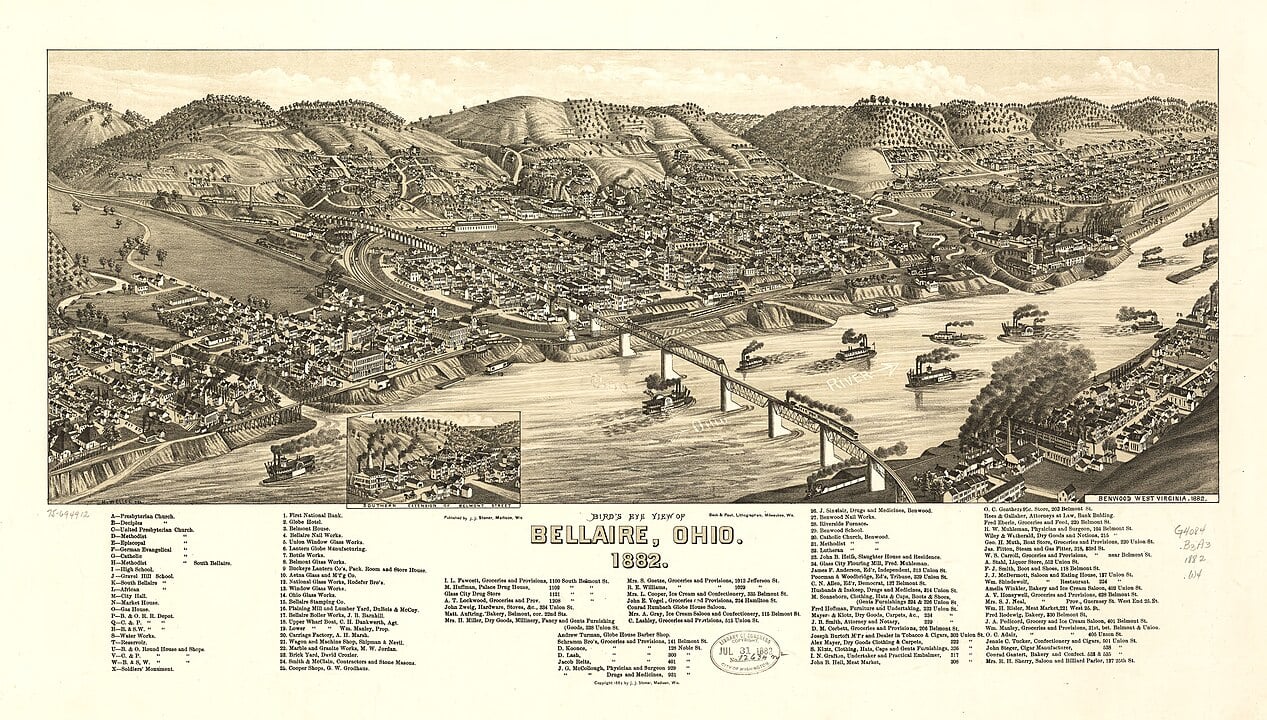

2. Bellaire (Belmont County)

Would you like to save this?

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Bellaire was known as the “Glass City,” with factories producing glassware that was shipped across the nation. It bustled with workers, shops, and river traffic.

Why it went bust

The glass industry collapsed as production moved elsewhere. With no replacement industry, Bellaire slid into decline.

Current status?

Thousands still live there, but much of Bellaire looks derelict, with hollowed-out streets and shuttered shops — a ghost town inside a living town.

1. Mansfield (Richland County)

How it became a rich, thriving town?

Mansfield thrived on industry: tires, appliances, steel, and even military vehicles. Its population surged in the early 20th century, and its downtown gleamed with theaters and hotels.

Why it went bust

Factory closures from the 1970s onward gutted jobs. The city shrank, poverty spread, and its grand downtown lost its luster.

Current status?

Around 47,000 people still live in Mansfield. Parts of the city are abandoned, but it’s trying to reinvent itself with film tourism around the Ohio State Reformatory and heritage projects. It’s half-ghost, half-comeback story.

References

- Wikipedia – Moonville, Ohio

- Wikipedia – San Toy, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Vinton Furnace, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Providence, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Fallsville, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Rendville, Ohio

- Wikipedia – New Straitsville, Ohio

- Wikipedia – East Liverpool, Ohio

- Wikipedia – East Cleveland, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Mingo Junction, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Negley, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Ai, Ohio

- Wikipedia – Hammel and Millgrove, Ohio

- Wikipedia – List of Ghost Towns in Ohio (covers Airington, Ashery, Beagle, Blanchard Bridge, Egypt Mills)

- Ohio Ghost Town Exploration Co.

- Ghosttowns.com – Ohio Section

- Abandoned Online – Forgotten Communities in Ohio

- The Guardian – Cheshire Buyout, 2002

- TIME – East Liverpool’s Pottery Decline

Haven't Seen Yet

Curated from our most popular plans. Click any to explore.