Would you like to save this?

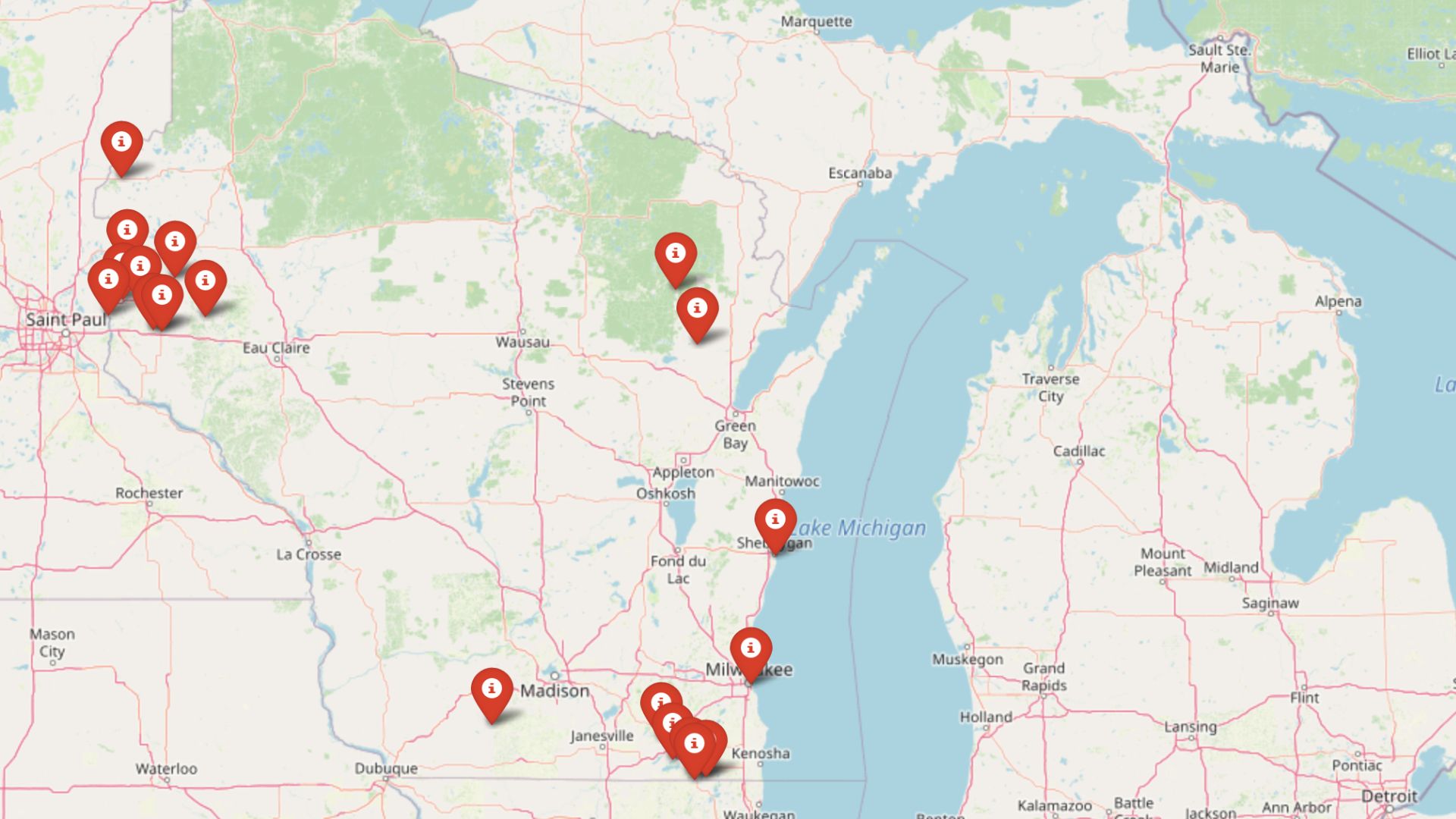

North of Highway 29, the grid of Wisconsin’s county roads thins into a mosaic of pine, peat bog, and glacier-chiseled lakes. Scattered across that land are tiny communities where loons outnumber people and the nearest chain store might be an hour away.

We gathered 25 of those settlements that quietly guard their solitude yet welcome visitors who respect the stillness. Each offers simple pleasures—paddling a glass-calm bay at dawn, sipping coffee under a sky streaked with Northern Lights, or hearing elk bugle through hemlock hills.

Readers will notice that tourism and forestry keep the lights on, but large land buffers, limited cell service, and long drives on forest roads preserve the hush. Count down with us from the most remote hamlets to the slightly larger lakeside villages that complete Northern Wisconsin’s secluded circle.

25. Herbster — South Shore Dunes and Wind-Swept Quiet

Herbster is the kind of Lake Superior hamlet you find by following gulls and a ribbon of two-lane blacktop, then wondering how it stayed this peaceful. Its seclusion comes from geography and restraint: wide sand, boreal forest, and no big marinas or neon to pull in crowds.

The vibe is wind-combed and unhurried—weathered cottages, dune grass hissing, a coffee thermos on a driftwood log. Walk the long public beach, watch storm fronts march across the lake, paddle the nearby Bark Bay Slough State Natural Area, or browse a tiny seasonal art shed on the shore.

Logging, small trades, and summer rentals support the week without breaking the hush. At dusk, the horizon turns pewter, and the only sound is the long breath of the lake. It’s the kind of place that teaches you to listen again.

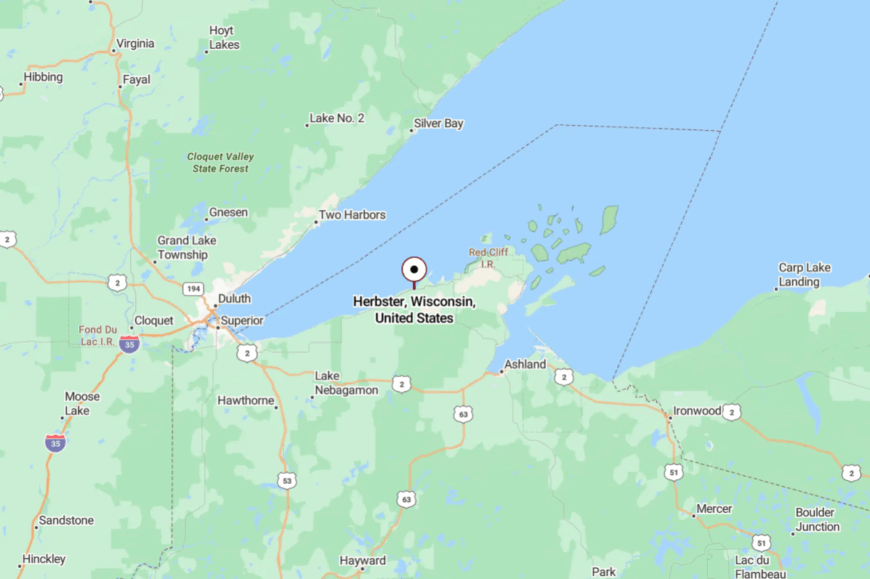

Where is Herbster?

Herbster sits on Wisconsin’s far north shore in Bayfield County, about 45 miles east of Superior and 3 miles west of Port Wing. Most visitors follow Highway 13 along the South Shore before turning onto short beachfront lanes.

With Superior on one side and the forest on the other, there’s no through-route to quicken the pace. It’s close enough for a day trip, but the last mile feels like a secret.

24. Port Wing — Siskiwit Bay, Breakwalls, and Big Evening Skies

Port Wing holds to a deep bay guarded by breakwalls, a compact village where fishing skiffs outnumber cars at dawn. Seclusion comes from the long sweep of forest behind it and Lake Superior in front—there’s simply nowhere for traffic to go.

The vibe is hardy and salt-tinged: boardwalks, weathered piers, and gulls arguing with the wind. Amble the beach at Port Wing Boreal Forest SNA, cast for salmon from the pier, follow the Siskiwit River upstream, or dine with a sunset that fills the whole horizon.

A small marina, seasonal cafes, and cottage caretaking make up most of the local work. Nights are dark and quiet, with waves counting the minutes. It’s a shoreline that asks you to slow to the water’s rhythm.

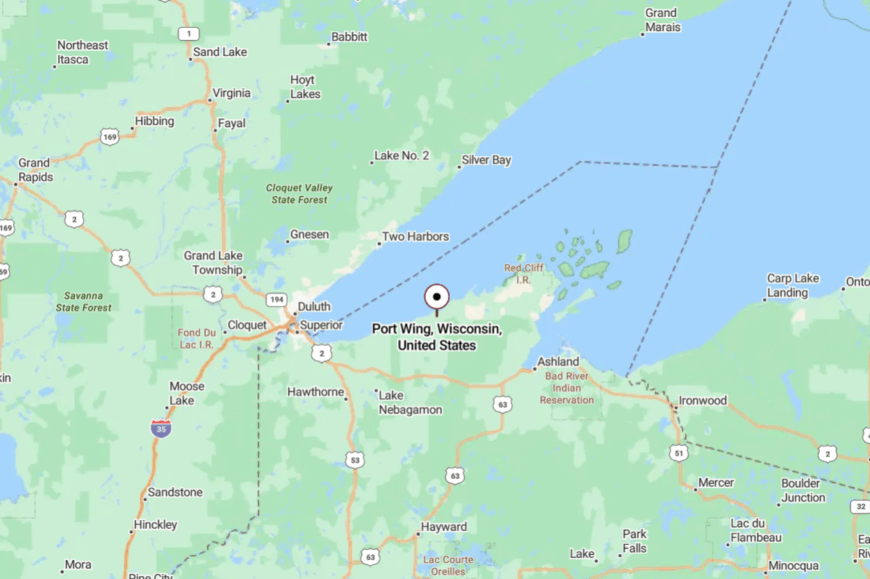

Where is Port Wing?

Kitchen Style?

On Bayfield County’s western edge, Port Wing sits along Highway 13 roughly 50 miles east of Duluth–Superior. Approach on the Seaway-style two-lane highway that rises and falls between forest and lake bluffs. Side streets dead-end at sand and rock, keeping drive-throughs to nil. You’ll know you’ve arrived when the wind smells like spruce and spray.

23. Cornucopia — Working Harbor at the Edge of the Apostles

Cornucopia is a tiny harbor town that feels like the last outpost before open water, with colorful sheds and fishing nets drying in the sun. Its tucked-away feel comes from the Bayfield Peninsula’s folded roads and the way County C just…stops at the lake.

The vibe is salty and artsy: a century-old general store, a few studios, and boats chiming against their lines. Walk the harbor, beachcomb after a blow, hike the Meyers Beach trail to Apostle Islands sea-cave overlooks, or sip coffee watching fog lift off Siskiwit Bay.

Fishing, guiding, and careful tourism keep the lights on without crowding the shoreline. When Superior goes mirror-calm, the harbor looks painted into place. It’s a little village with a big horizon.

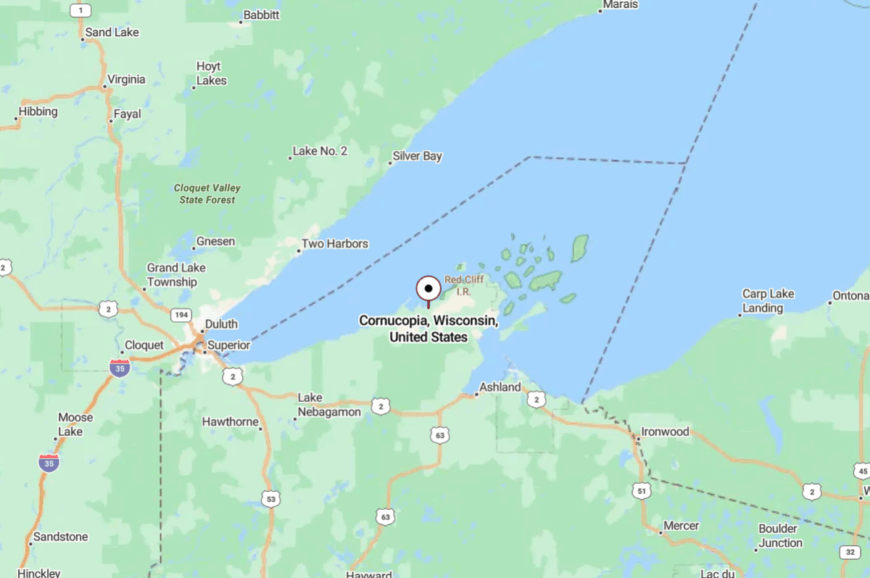

Where is Cornucopia?

Cornucopia sits on the south shore of Lake Superior in Bayfield County, about 25 miles west of Bayfield and 35 miles northeast of Superior. From Highway 13, turn north on County C as it narrows toward the lake.

The last miles curve through cedar and hemlock before the harbor appears. It’s close to famous sights, yet feels blissfully apart from them.

22. La Pointe (Madeline Island) — Ferry Miles from the Mainland

Home Stratosphere Guide

Your Personality Already Knows

How Your Home Should Feel

113 pages of room-by-room design guidance built around your actual brain, your actual habits, and the way you actually live.

You might be an ISFJ or INFP designer…

You design through feeling — your spaces are personal, comforting, and full of meaning. The guide covers your exact color palettes, room layouts, and the one mistake your type always makes.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ISTJ or INTJ designer…

You crave order, function, and visual calm. The guide shows you how to create spaces that feel both serene and intentional — without ending up sterile.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ENFP or ESTP designer…

You design by instinct and energy. Your home should feel alive. The guide shows you how to channel that into rooms that feel curated, not chaotic.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

You might be an ENTJ or ESTJ designer…

You value quality, structure, and things done right. The guide gives you the framework to build rooms that feel polished without overthinking every detail.

The full guide maps all 16 types to specific rooms, palettes & furniture picks ↓

La Pointe keeps an island tempo: gulls, bicycle bells, and the soft thrum of the ferry when it glides in. Seclusion is baked in—this is the only inhabited Apostle Island, and lake ice or wind sometimes decides how the day will go.

The vibe is breezy and bohemian: clapboard shops, tiny museums, and porches facing a sweep of blue. Beach hop at Town Park, paddle out to sea-smoothed boulders, visit local history exhibits, or browse studios before catching a sunset ferry.

Summer tourism, light trades, and seasonal service jobs keep things modest and friendly. Nights arrive with loon calls that carry across the channel. It’s a short crossing to a different pace of life.

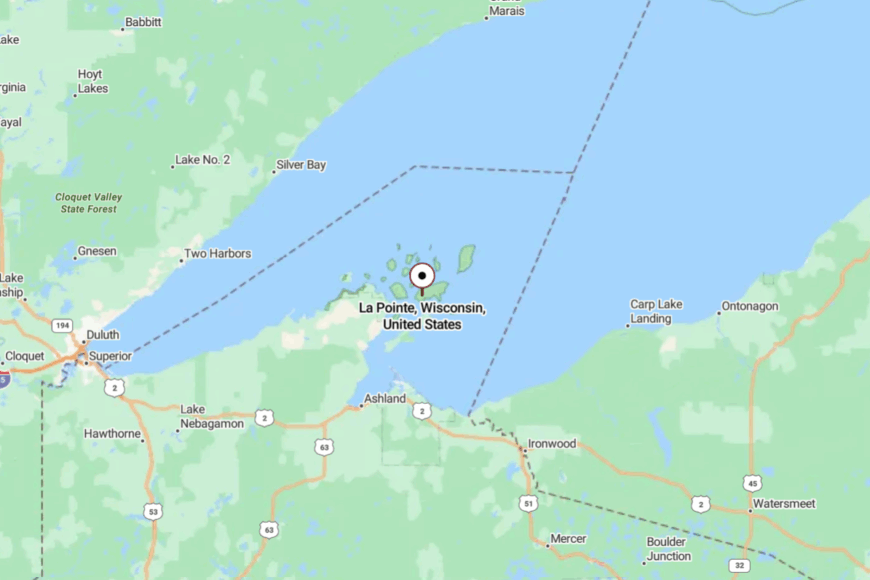

Where is La Pointe?

La Pointe is on Madeline Island just off the Bayfield Peninsula in far northern Bayfield County. Most travelers reach it by ferry from Bayfield; in deep winter, specialized craft or seasonal ice routes may change the routine.

On the island, narrow lanes thread forest and shore rather than racing anywhere. It’s close enough to see the mainland lights, but far enough to feel freed from them.

21. Brule — River Town Where Paddles Replace Horns

Brule is wrapped around the Bois Brule River, a cold, quick thread that shapes daily life more than any highway. Its seclusion comes from the surrounding state forest and the absence of big services between here and Superior.

The vibe is classic northwoods: cedar-scented air, old cabins tucked under pine, a diner with muddy wader prints by the door. Drift the river in a canoe, fish riffles at first light, hike pine-needle trails, or tour historic sites tied to famous anglers.

Guiding, small hospitality, and forestry steady the calendar. Even the main street sounds like water more than engines. It’s a village where time moves at the speed of the current.

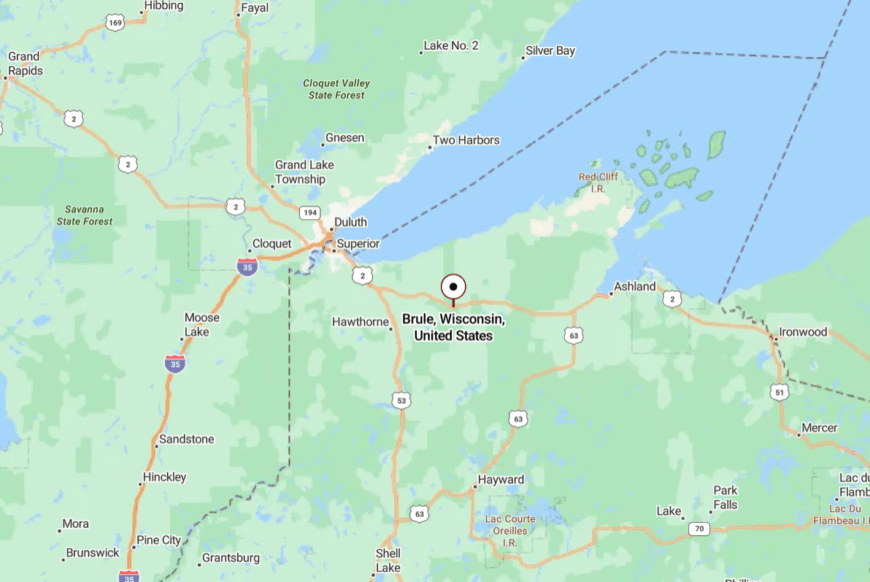

Where is Brule?

Brule sits in eastern Douglas County along U.S. Highway 2, about 35 miles east of Superior. Turn south toward the river, and the woods swallow road noise within minutes.

Forest roads and river bends keep everything measured and quiet. It’s easily reached, yet it feels like a world tucked behind the pines.

20. Drummond — Lakes, Aspen Ridges, and a Single Main Street

Drummond strings a few essentials along U.S. 63 and lets the forest do the rest. Seclusion here is a matter of acreage: county and national lands stretch in every direction, breaking up sightlines and traffic.

The vibe is cabin-cozy and trail-happy—canoes on car roofs, bikes dusty from CAMBA singletrack, and supper clubs glowing after dark. Fish inland lakes, follow snowmobile corridors that double as summer ATV routes, hike North Country Trail segments, or explore a small logging museum.

Timber work, guiding, and seasonal cabins make up the local economy. After sunset, the sky goes truly black, and frogs take over the soundtrack. It’s a practical gateway to a very big quiet.

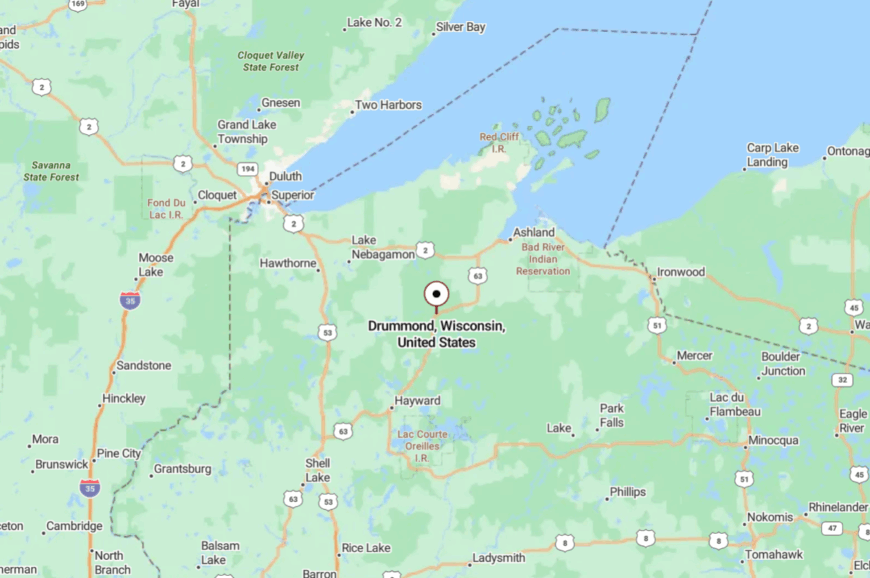

Where is Drummond?

Find Drummond in central Bayfield County, about 40 miles southwest of Ashland and 25 miles northeast of Hayward. U.S. 63 gets you there, then forest lanes spin off to lakes and trailheads.

With no expressway nearby, even through-traffic slows. You arrive and immediately breathe deeper.

19. Butternut — Village Life Near Dark, Still Lakes

Butternut is a front-porch village where musky lakes and maple stands begin right past the last streetlight. Its tucked-away feel comes from being south of Ashland and north of Park Falls with long stretches of woods between.

The vibe is small and sincere: ballfields, a classic bar for Friday fish fry, and early-morning boats sliding onto glassy water. Cast on Butternut or nearby lakes, ride quiet county roads, browse a pocket museum, or snowmobile straight from town when the base sets.

Logging, small shops, and lake tourism keep the week turning. Dusk here smells like pine and outboard fuel in the best possible way. It’s a simple place that stays close to the water’s calm.

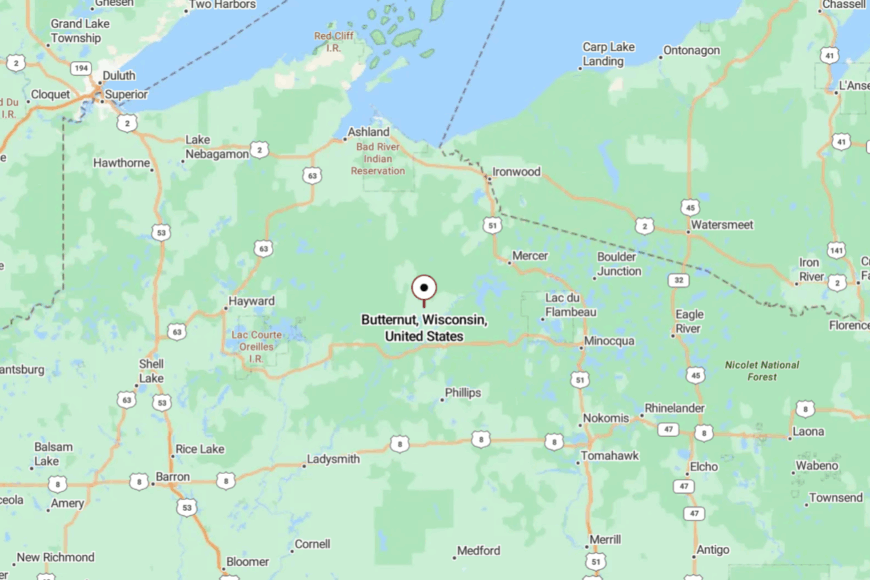

Where is Butternut?

Butternut sits along Highway 13 in southern Ashland County, about 8 miles north of Park Falls and 40 miles south of Ashland. Approaches are easy, but trees close in quickly once you leave the highway.

Lakes and forest back right up to the village grid, muting everything. It’s near the road, yet it feels quietly off to the side.

18. Mellen — Copper Falls and Red-Rock Quiet

Mellen wears its logging roots lightly and lets Copper Falls State Park do most of the talking. Seclusion comes from sandstone gorges and big forest blocks that keep development at arm’s length.

The vibe is rugged and scenic: red rock, thundering falls, and a tidy main street where hikers trade trail notes. Hike the Doughboys Trail, photograph cascades at sunrise, bike low-traffic county lanes, or warm up in a classic northern café.

Small manufacturing, park visitors, and timber work share the week. When evening fog lifts from the Bad River gorge, the town feels wrapped in its own weather. It’s a gateway where nature sets the schedule.

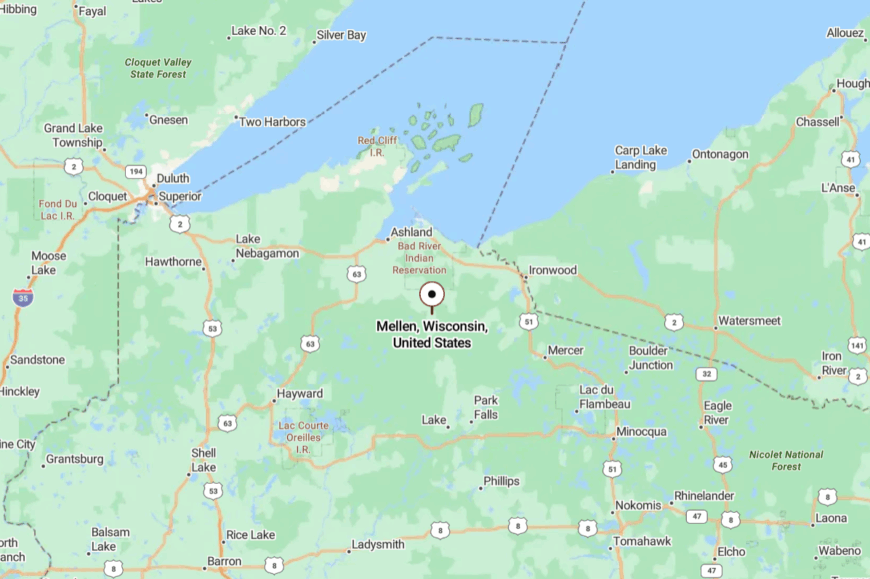

Where is Mellen?

Mellen sits on Highway 13 in southern Ashland County, about 25 miles south of Ashland and 15 miles west of Highway 51. From town, WI-169 hops to Copper Falls along a winding, wooded route.

The gorge walls and pines blunt the noise of any passing trucks. You’re minutes from the highway and a world away in spirit.

17. Winter — Trail Hub With a Front-Porch Heart

Winter keeps a few blocks of shops and lets the rest of life stretch into the pines. Its seclusion comes from long runs of county forest and the way the Tuscobia State Trail replaces car traffic with bikes, sleds, and ATVs.

The vibe is plainspoken and outdoorsy: thermoses at dawn, trail dust on boots, and a café that knows your order by the second visit. Ride the Tuscobia, fish the nearby Chippewa and Brunet systems, paddle little kettle lakes, or browse a small museum on logging days.

Guiding, trail tourism, and school events anchor the calendar. On still nights, you can hear trains far off and owls closer in. It’s a low-key base camp for quiet adventures.

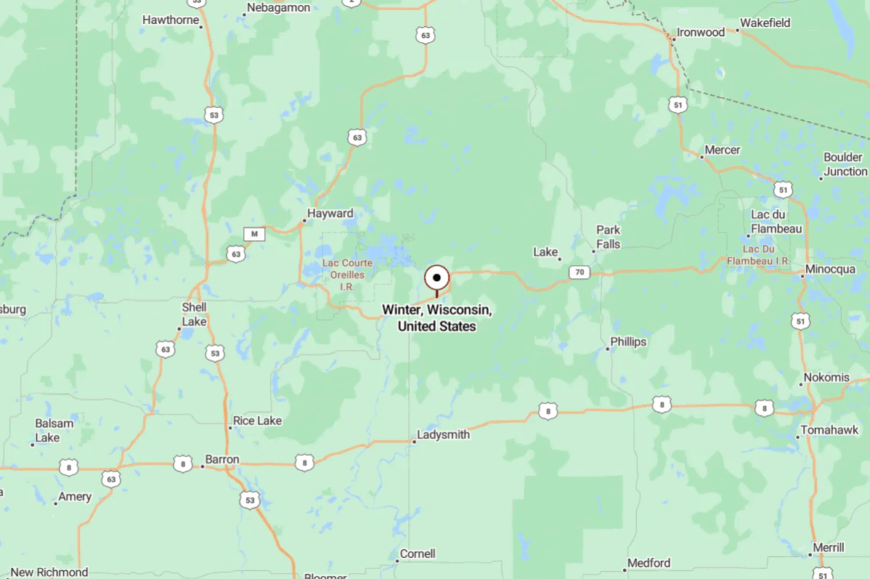

Where is Winter?

Winter lies along Highway 70 in eastern Sawyer County, about 20 miles east of Hayward. The last minutes into town pass more pines than porches.

Side roads quickly narrow to gravel and forest spurs. It’s easy to find and easier to forget the rush you came from.

16. Couderay — River Bends and Prohibition-Era Lore

Would you like to save this?

Couderay is tiny enough to miss if you blink, a cluster of buildings near the river that gave it a name. Seclusion is guaranteed by the Chippewa Flowage to the north and big woods all around—most roads either curve back or end at water.

The vibe is hushed and a little storied: quiet bars, fishing tales, and an old lodge tied to Prohibition-era legend. Cast the Couderay River, explore back-bays of the Flowage by kayak, walk sandy fire lanes lined with blueberries, or angle for crappie at sunset.

Guiding, seasonal cabins, and a few service jobs make up the local economy. Evening brings loon calls that feel close enough to touch. It’s the sort of quiet that makes you whisper without meaning to.

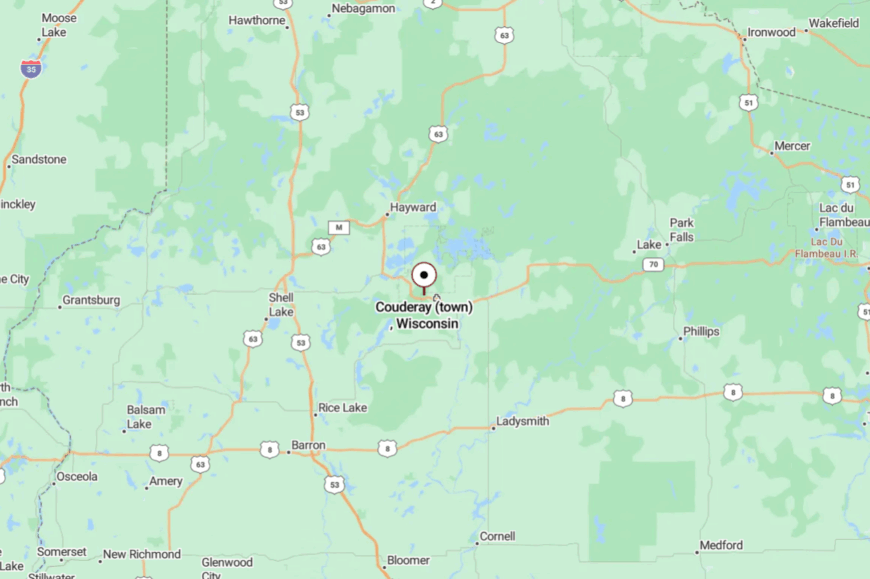

Where is Couderay?

Couderay sits along Highways 27/70 in southeastern Sawyer County, about 16 miles southeast of Hayward. Once you turn off the highway, short lanes quickly trade pavement for pine needles.

Water and woods hem the hamlet on three sides. It’s near the map’s bold lines, yet tucked into its own green pocket.

15. Fifield — Flambeau Forks and Tall Pines

Fifield is a crossroads surrounded by rivers that prefer canoes to schedules. Its seclusion comes from the Chequamegon–Nicolet’s deep pine and the wide reach of the Flambeau River State Forest east of town.

The vibe is northwoods-practical: bait coolers on porches, stacked firewood, and supper clubs glowing in the trees. Paddle the North or South Fork of the Flambeau, hike old logging grades now turned trails, cast for smallmouth under cedar shade, or roll a lazy county-road bike loop.

Timber, guiding, and a handful of traveler services keep the lights on. When the wind runs the pines, it sounds like the river speaking. It’s a place that trades hurry for current.

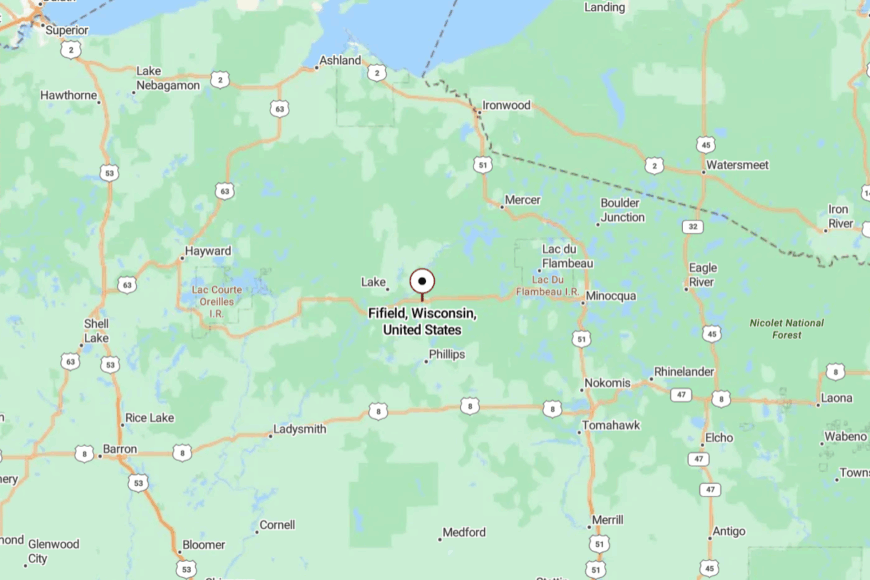

Where is Fifield?

Fifield sits where Highways 13 and 70 meet in central Price County, about 6 miles south of Park Falls. From town, Highway 70 slips east into long runs of forest with few intersections.

With no interstate nearby, everything moves at a two-lane rhythm. You feel the hush deepen as trees thicken.

14. Mercer — Loon Calls Over the Turtle-Flambeau

Mercer wakes to loon calls echoing across the Turtle-Flambeau Flowage and spends the rest of the day matching that calm. Its secluded feel comes from 19,000 acres of island-studded water and public shoreline that keep density low.

The vibe is water-bound and easygoing: bait shops, docks, and quiet roads where deer step out at dusk. Paddle to granite points, cast for walleye, bike the Heart of Vilas trail segments, or snowmobile to far-off warming huts when winter lays its hush.

Tourism and cabin care carry the week, with small trades filling gaps. Sunsets turn the flowage copper and conversations softer. It’s an address with more sky than schedule.

Where is Mercer?

Mercer sits on U.S. 51 in Iron County, about 15 miles south of Hurley and the Michigan line. Side roads peel off the highway and vanish into bays and peninsulas.

With vast public lands to the west, there’s no shortcut through town. It’s easy to reach, yet deliberately unhurried.

13. Winchester — Border Lakes and Back-Road Stillness

Winchester is mostly water, spruce, and sky, with homes tucked so far back you hear loons before you spot mailboxes. Seclusion comes from its far-north position and a web of lakes that replace straight roads with wandering peninsulas.

The vibe is porch-swing and paddle-quiet: coffee at first light, eagles overhead, and a skiff nosing into lily pads. Portage between chain lakes, explore pocket sandbars, bike the shoulderless backroads, or watch stars from a dock that feels like a raft to the cosmos.

Cabin caretaking, guiding, and a few trades keep things humming just enough. Even the dogs seem to bark softer here. It’s the kind of calm that soaks in like sun on a pier.

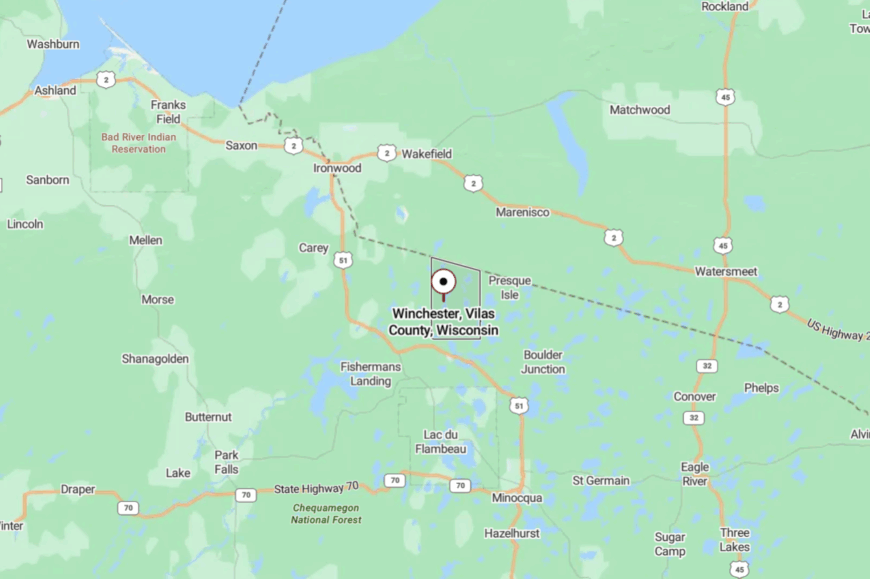

Where is Winchester?

On Vilas County’s northwest edge, Winchester borders Michigan and sits west of Presque Isle by a few easy miles. County W and narrow lake lanes handle most travel; there’s no fast alternative.

Water and forest break sightlines and slow speed by design. It’s close to the line on the map, far from any rush.

12. Phelps — Pines, Twin Lakes, and Early-Riser Quiet

Phelps gathers around North and Big Twin Lakes with streets that end in boat landings and birdsong. Its seclusion comes from national forest to the east and long distances to big box anything in any direction.

The vibe is old-time lake town: cedar-scented air, neat docks, and a hardware store that doubles as a conversation post. Fish dawn topwater for smallies, hike to hemlock bogs, follow a snowshoe loop after a fresh fall, or tour a cranberry marsh when harvest glows red.

Tourism, cabin care, and a few makers and outfitters carry the week. Even busy weekends feel gentle along the quieter bays. It’s a place that moves at the speed of a paddle stroke.

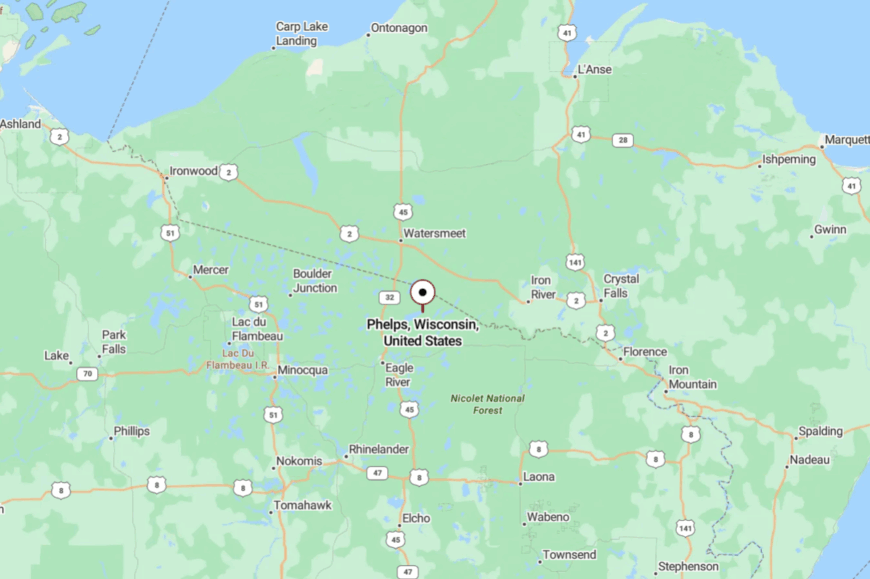

Where is Phelps?

Phelps sits in northeastern Vilas County about 15 miles northeast of Eagle River via Highway 17. The last miles roll between lakes and pines with no need for passing lanes.

Forest on three sides narrows the world to water and sky. It’s close enough for groceries, far enough for stars.

11. Hiles — Boardwalks, Bogs, and Pine-Shadow Peace

Hiles is more whisper than town—cabins under towering red pines, a tiny post office, and lakes that hold morning fog like a bowl. Its seclusion comes from big blocks of Nicolet forest and quiet federal campgrounds where generators yield to loons and barred owls.

The vibe is hushed and moss-soft: wooden boardwalks over pitcher-plant bogs, shorelines laced with white cedar, and gravel lanes that end at water. Stroll the Franklin Nature Trail boardwalk, paddle Pine or Franklin Lakes at dawn, fish under cedar shade, or watch night skies from a dark public landing.

Seasonal campground hosts, cabin caretakers, and a few guides keep the calendar. Here, time seems to drift like pollen on still water. It’s the kind of quiet that you carry home.

Where is Hiles?

Hiles lies in northern Forest County about 20 miles northeast of Crandon, reached by Highways 32/55 and then forest roads. The last stretch narrows under pine canopies as lakes flash between trunks.

With no through route, traffic thins to canoes and pickup trucks. It’s close enough to reach, but far enough to leave everything else behind.

10. Clam Lake — An Elk-Roaming Hamlet Deep in the Chequamegon

Clam Lake claims roughly 40 full-time residents who share their backyards with a reintroduced elk herd. Snowmobilers, bird-watchers, and stargazers slip into town for trail connections, elk tours, and the legendary Friday fish fry at Clam Lake Junction.

Timber management and a handful of seasonal resorts provide the only steady paychecks, reinforcing a do-it-yourself culture where locals also tap maple trees and guide hunters. Even at summer peak, cabins sit on one-acre forest lots that block any neighbor’s porch light, and the nearest gas pump is a 30-minute drive.

Dark-sky ordinances and the 1.5-million-acre Chequamegon–Nicolet National Forest all but erase noise pollution, so nightfall belongs to barred owls and the Milky Way. Anyone searching for genuine back-of-beyond quiet finds it here, punctuated only by the eerie whistle of bugling elk in September.

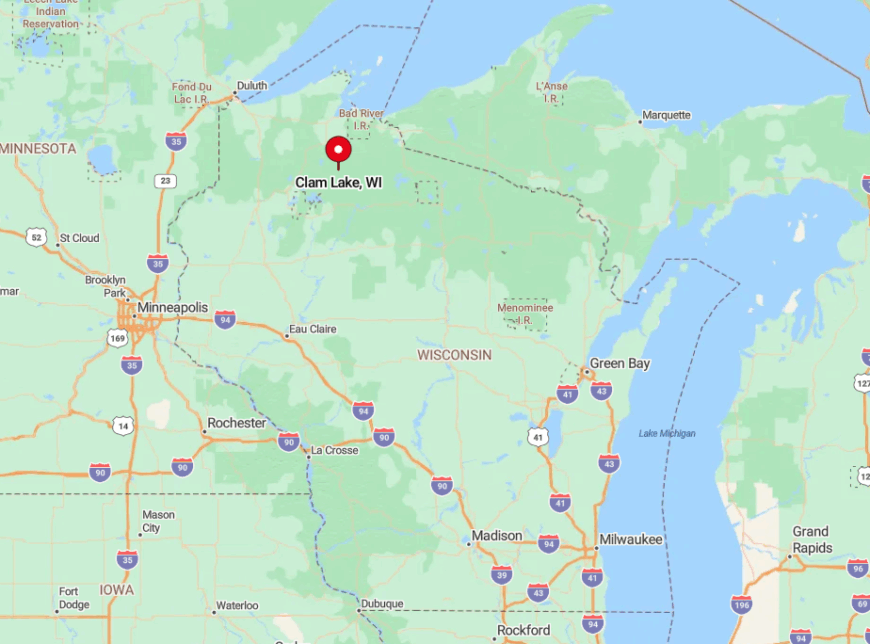

Where is Clam Lake?

The hamlet nestles at the junction of County Highways GG and M in southern Ashland County. With 20 miles of forest between it and U.S. Highway 63, rugged terrain and limited cell towers reinforce the isolation.

Travelers usually exit State Highway 77 at Clam Lake Road, then wind past beaver ponds before the first porch light appears. During winter, snowmobile Trail 8 becomes a secondary “highway” that many residents rely on more than pavement.

9. Delta — Kettle-Lake Reflections and Hemlock Hills

Delta Township keeps its year-round head count near 250, leaving plenty of room for the hemlock, maple, and cedar that dominate every horizon.

Photographers glide out before sunrise to catch mirror-still reflections on Pike, Twin Bear, or Larson lakes, while anglers chase walleye and stocked brook trout just steps from roadside carry-ins.

A scattering of century-old dairy farm clearings supports hobby hay operations, but seasonal cabin rentals and the famed retro-blue Delta Diner fuel most local income. Houses sit a mile apart on gravel lanes, and several dozen kettle lakes have no formal boat landings at all, ensuring mornings when loons echo without interruption.

Neighbors here wave from ATVs more often than sedans, and porch lights disappear entirely once the fall color rush passes. The combination of thick forest, minimal commerce, and quiet water surfaces creates a pocket of calm rarely broken by traffic.

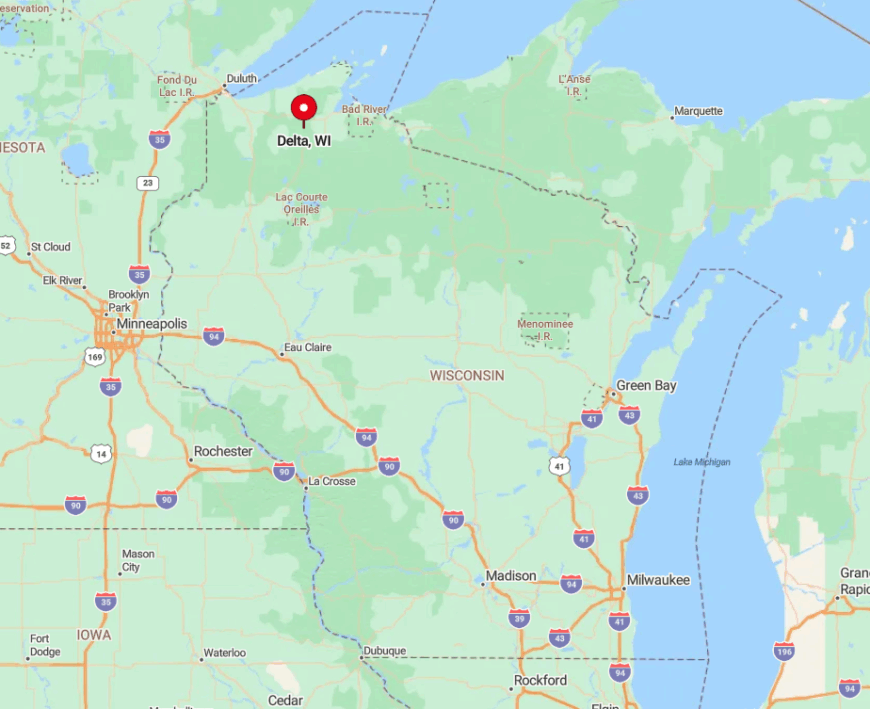

Where is Delta?

Delta lies 12 miles southeast of Iron River in Bayfield County’s hill country. The township is wedged between forest-service tracts, so state highways detour around, not through, its core.

Visitors reach Delta by turning south off U.S. Highway 2 onto County H, then following gravel spurs like Delta-Drummond Road. Lack of through-routes keeps GPS shortcuts away and preserves the township’s hard-to-find feel.

8. Presque Isle — Wisconsin’s Last Wilderness on the Border

Roughly 600 residents share Presque Isle’s 70 square miles of mixed hardwood and pine, stitched together by more than 1,000 glacier-carved lakes. Paddlers trace sapphire shorelines, anglers pull trophy musky, and hikers step onto portions of the North Country Trail that carve through old-growth white pine.

Cottage maintenance, guide services, and small-scale forestry form the backbone of local work, with a few heritage resorts filling in seasonal gaps. Waterfront parcels average several acres, and houses hide behind cedar ridges so effectively that boat lights are often the only hints of human presence.

The town bans street lighting in most zones, allowing meteor showers and Northern Lights to claim the night sky. Its “Last Wilderness” nickname holds true each winter when silent snowfall buries side roads and cuts the village off from casual day-trippers.

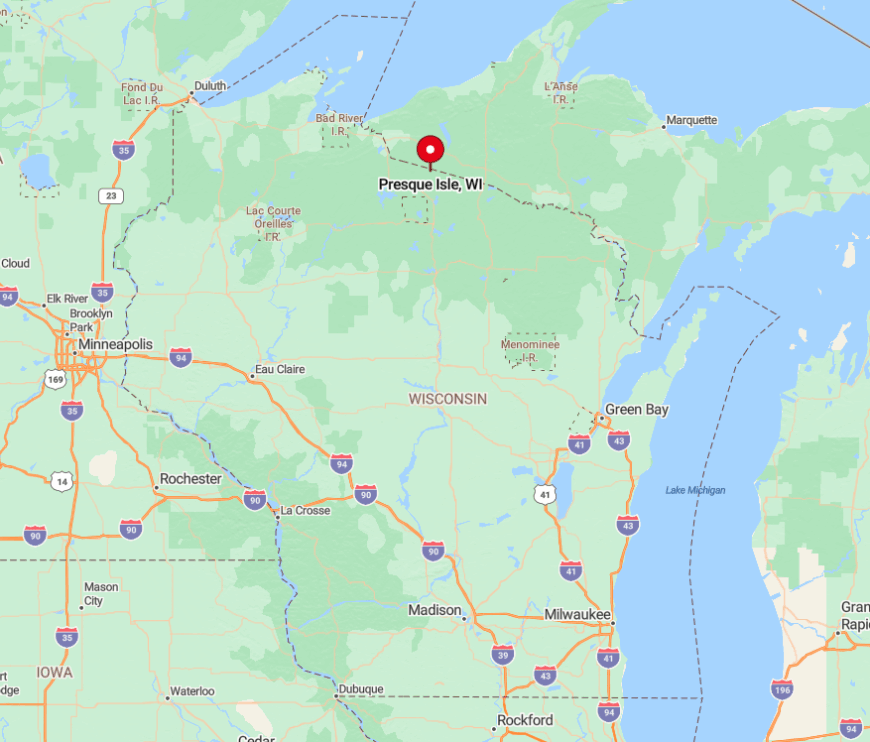

Where is Presque Isle?

The community caps Wisconsin’s northernmost tip in Vilas County, nudging against Michigan’s Ottawa National Forest. Only State Highway B threads through dense timber before dead-ending at the border, leaving 30 miles of forest between Presque Isle and the nearest big-box store in Minocqua.

Most visitors arrive via County Highway W, a two-lane ribbon that traces lake shores and tight S-curves, naturally slowing traffic. Those who make the trip are rewarded with uncrowded landings and dark-sky nights far from interstate glare.

7. Glidden — Black Bear Capital Wrapped in County Forest

Would you like to save this?

Glidden’s population hovers below 500, yet the town proudly bills itself the “Black Bear Capital of Wisconsin.” Hunters and berry pickers roam 80-percent county-owned forest, while cyclists tackle rustic gravel routes that weave past oak and aspen ridges.

A single grocery-hardware hybrid and a sawmill anchor the micro-economy, complemented by guiding outfits that specialize in black bear and grouse seasons. Cell service flickers between ridgelines, and most gravel roads transition to sandy two-tracks that deter casual exploration.

Even the local school closed decades ago, emphasizing how the forest reclaims anything left unaided. The result is an up-north enclave where bear tracks in the driveway outnumber delivery trucks all year long.

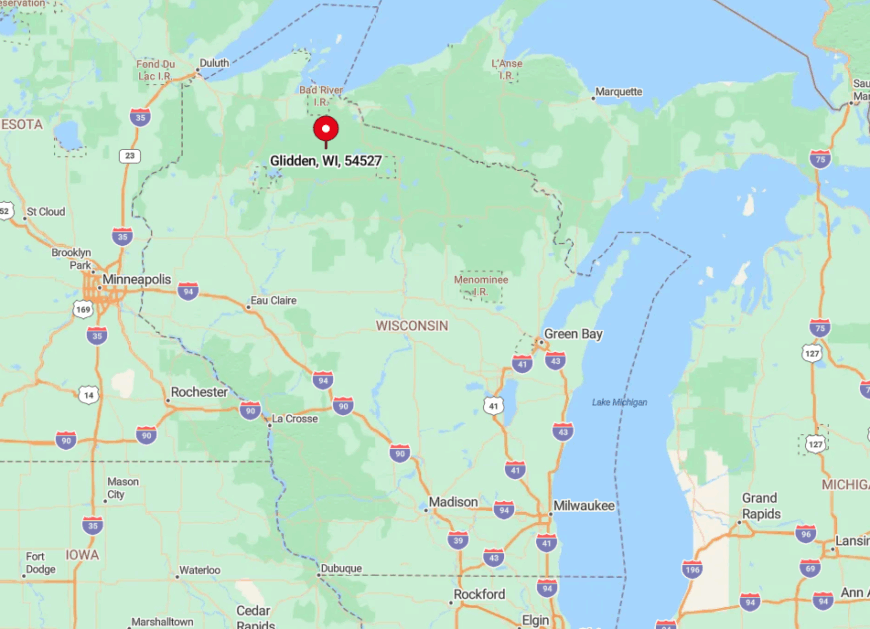

Where is Glidden?

Glidden sits on State Highway 13 between Park Falls and Mellen, but the pavement quickly yields to county forest roads in every direction. Ashland County’s timber blocks any direct interstate connection, creating a self-contained basin of woods and water.

Visitors typically exit U.S. Highway 51 at Highways 182 or 70, then wind 25 miles through forest before reaching town. Once there, gravel spurs like Forest Road 144 lead deeper into oak uplands where the only traffic jam might involve a sow and cubs.

6. Cable — Trailhead Village Amid 800,000 Acres of Pines

Cable logs about 800 year-round neighbors who cheer every February as the American Birkebeiner ski marathon glides down Main Street. Mountain bikers, Nordic skiers, and fat-bike racers treat the CAMBA trail network as a four-season playground, while anglers chase smallmouth on Namekagon River headwaters.

Aside from outdoor tourism, a handful of log-home builders and specialty coffee roasters keep saws and espresso machines humming. Houses generally occupy one- to five-acre parcels tucked along forest lanes, and a 45-minute drive separates Cable from the nearest big-box store in Hayward or Ashland.

After dusk, silence settles like fresh snow because no major highway pierces the surrounding 800,000 acres of county and national forest. That vast land buffer turns Cable into a trailhead village that feels far removed from modern haste.

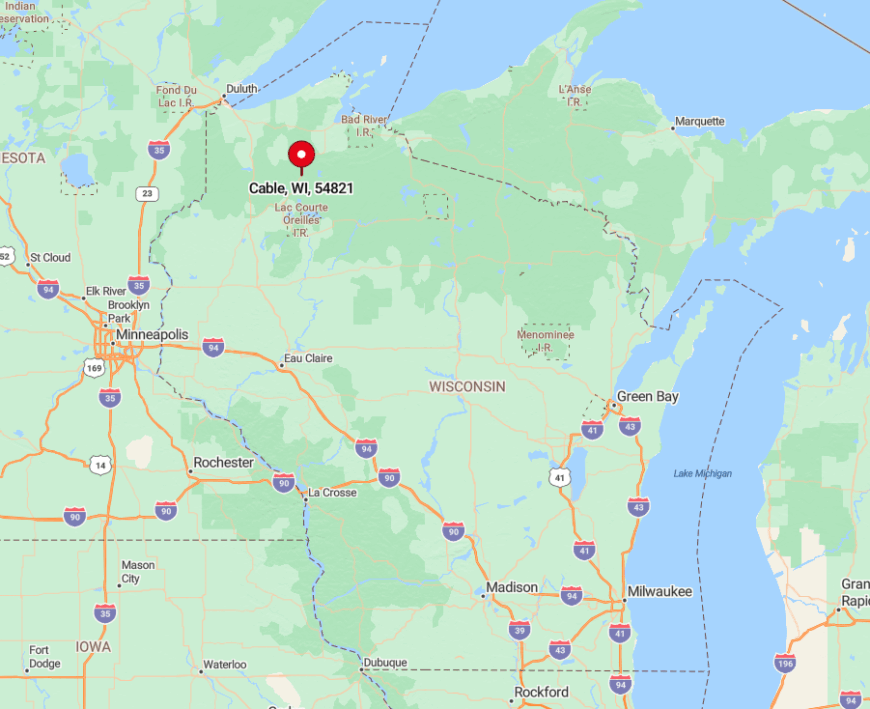

Where is Cable?

Find Cable along U.S. Highway 63 in Bayfield County, midway between Hayward and Ashland. Though the highway clips the village, dense pine stands absorb most road noise within a quarter-mile.

Visitors aiming for trailheads turn onto Randysek or McNaught Roads, soon trading asphalt for hard-pack forest lanes. The closest commercial airport lies 90 minutes west in Duluth, underscoring Cable’s lightly traveled setting.

5. Land O’ Lakes — Northern Lights Over Peat Bogs and Spruce

About 900 residents scatter across a patchwork of peat bogs, spring-fed lakes, and glacial eskers that define Land O’ Lakes. Paddlers slip canoes into the Black Oak or Cisco chains, while skygazers gather at Conserve School’s athletic field for some of the Midwest’s best aurora displays.

Tourism, small-scale cranberry farming, and cross-border trade with Michigan’s Upper Peninsula generate modest income streams. Many log homes hide on private lakes reachable only by gravel spurs that weave 15 miles from any town center, preserving an enveloping hush.

Ottawa National Forest hems the community on two sides, and night skies remain inky with stars thanks to minimal lighting. Those who stay the weekend often discover secret boardwalks to carnivorous pitcher-plant bogs that rarely appear in guidebooks.

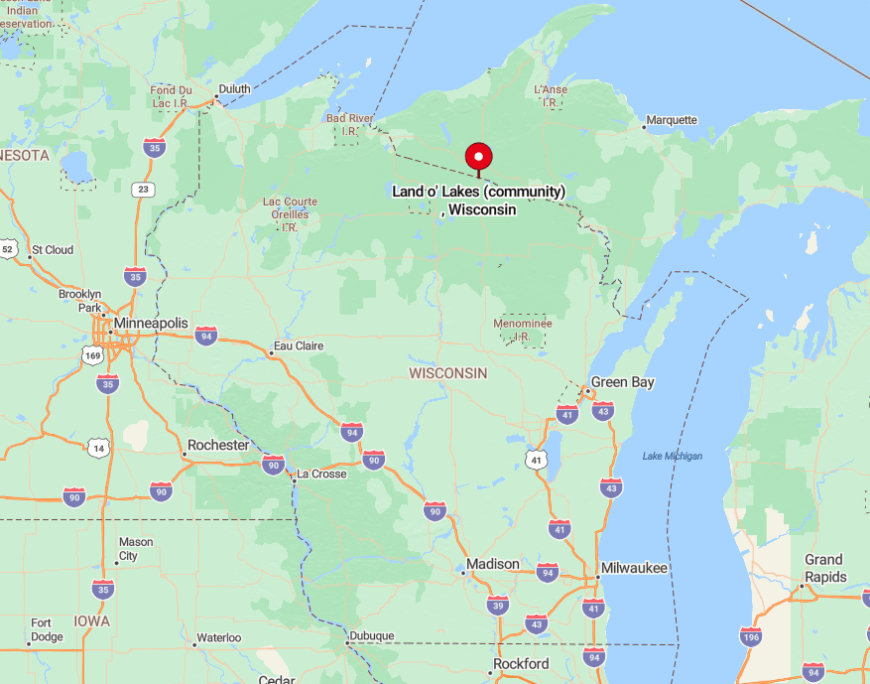

Where is Land O’ Lakes?

The village touches the Michigan border at the junction of U.S. Highway 45 and County B in Vilas County. North and west of that crossroad, federal forest blocks urban expansion and funnels traffic onto a single north–south corridor.

Travelers from the south exit Interstate 39 at Wausau, then meander two hours through forest and farm before the first Land O’ Lakes sign. Winter visitors often arrive by snowmobile on the 1,000-mile “Snowmobile Capital” trail network rather than by car.

4. Namakagon — Quiet Bays at the Namekagon River Headwaters

Namakagon counts roughly 300 residents scattered around the sprawling Lake Namakagon and its maze of shielded bays.

Lake-trout anglers, paddleboarders, and bald-eagle watchers relish having entire coves to themselves on weekday mornings, while the nearby Rock Lake mountain-bike loop rewards riders with moss-carpeted cedar stands.

Tourism and a modest timber harvest support the tax base, supplemented by family-run supper clubs glowing with neon walleyes on Friday nights. Population density stays under ten people per square mile because the township enforces five-acre minimum lot sizes and bans multi-slip marinas.

The Namekagon River, protected as part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system, limits shoreline development and preserves primeval vistas. Together, these policies guarantee that launching a canoe still feels like stepping onto a private lake.

Where is Namakagon?

The township sits south of Cable in Bayfield County, anchored by County Highway D’s gentle loop around Lake Namakagon. Extensive public lands and conservation easements block any shortcut to faster highways, lengthening the trip from Duluth or Eau Claire to nearly two hours.

Most visitors exit U.S. Highway 63 at Grand View, then follow curving forest roads that hug the river’s headwaters. The absence of cell towers in several bays ensures genuine digital detox before paddles even hit water.

3. Minong — Jack Pine Flats and Blueberry Bogs Off the Grid

Minong’s village and surrounding town combine for about 600 permanent residents who trade suburban lawns for five-acre jack-pine glades. Residents ride ATVs on sand barrens to pick July blueberries, fish for crappie on 1,500-acre Minong Flowage, and join Friday night card games at the rustic Totogatic Lodge.

Wood products giant Jack Link’s runs a jerky plant that shares the skyline with a single water tower, providing the area’s primary wage base alongside tourism. Cabin compounds often rely on solar panels because power lines skip whole stretches of county forest, reflecting the community’s semi-off-grid character.

Only one two-lane highway—U.S. 53—connects Minong to Duluth nearly an hour west, so traffic stays light and night skies dark. Many newcomers are shocked to learn the local grocery stores still close by 7 p.m., leaving owl calls as the only after-hours soundtrack.

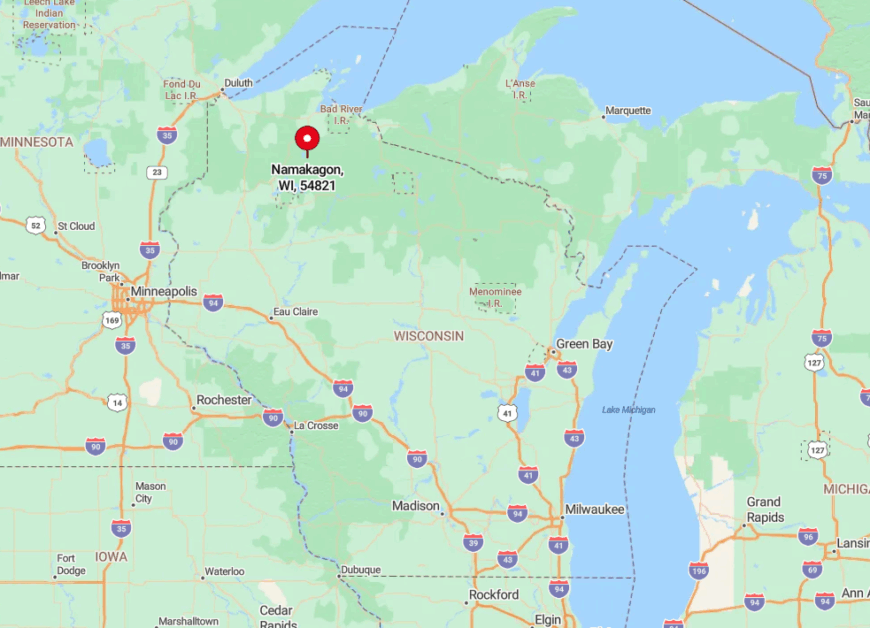

Where is Minong?

Minong anchors northwest Washburn County at the junction of U.S. 53 and County I. Beyond that crossroads, jack-pine savannas sprawl toward the Totogatic River with sparse development.

Those driving from Minneapolis exit Interstate 35 onto State Highway 70, then weave 40 miles through forest before reaching U.S. 53’s straight shot north. Freight trains still outnumber semis, underscoring Minong’s lightly trafficked remoteness.

2. Moose Lake — Chippewa Flowage Islands and Vintage Cabins

Around 75 hardy souls call the Moose Lake area home year-round, living among the 15,000-acre Chippewa Flowage’s labyrinth of muskeg islands. Anglers chase legendary “flowage muskies,” kayakers glide between sphagnum-rimmed coves, and photographers paddle out at dawn to catch fog lifting off glassy channels.

Tiny vintage resorts and guiding outfits supply the limited employment, while occasional selective logging keeps forest roads passable. Most cabins sit on peninsula lots accessible only by a 12-mile forest road or boat, ensuring the hiss of propane lamps is louder than passing cars.

Even summer weekends feel quiet because no marina offers more than a handful of slips and cell reception disappears after the first bend in the river. As dusk falls, loons echo across the water, reminding guests why road noise never made it this far.

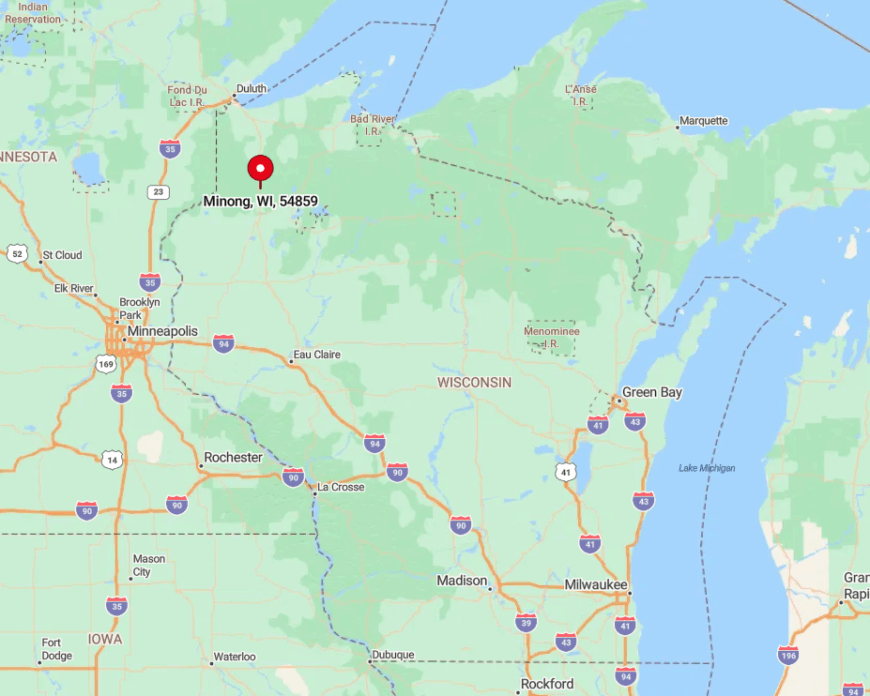

Where is Moose Lake?

The enclave lies 25 miles southeast of Hayward at the terminus of County Highway S in Sawyer County. Beyond the pavement, Forest Road 174 meanders another 12 miles before dead-ending at the dam that created the Chippewa Flowage.

Visitors often trailer boats from Hayward, then navigate island channels to reach cabin docks that lack road addresses. This boat-or-bust approach keeps Moose Lake quietly tucked away behind its maze of water and spruce.

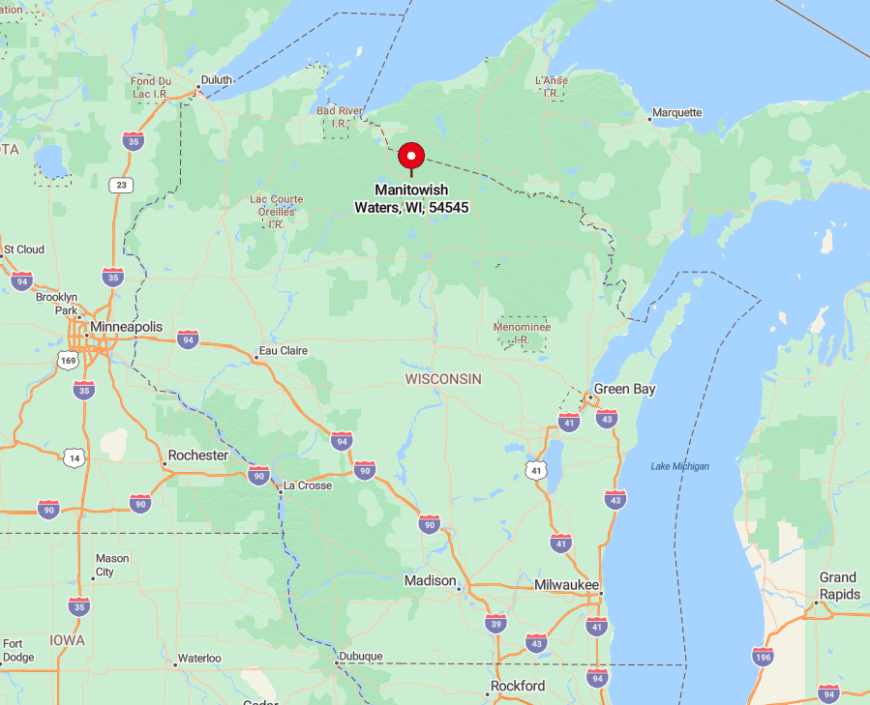

1. Manitowish Waters — Loons, Pines and Ten Interlocked Lakes

Manitowish Waters guards a steady population of just over 600 who wake to loon calls echoing across ten interlocked lakes. Summer guests fish walleye, bike the Heart of Vilas County Trail, and sip cranberry wine at a farm where vines float on sandy bog mats.

Tourism and small-batch cranberry farming dominate payrolls, while a historic WWII snowmobile chalet-turned-bar nods to the area’s colorful past as a gangster hideout. Pine-clad lots start at two acres, and shoreline zoning caps development density, ensuring coves remain hushed even on holiday weekends.

A 30-mile cushion separates the community from Interstate 51, so traffic never overwhelms the single stoplight downtown. Evening settles in with barred owl trills and campfire smoke curling over the water—an everyday reminder of why residents trade convenience for calm.

Where is Manitowish Waters?

The village sits at the intersection of U.S. Highway 51 and State Highway 47 in northern Vilas County. Despite that junction, dense state and national forest buffer the chain of lakes from heavy through-traffic.

Travelers from Madison face a four-hour drive north on U.S. 51, with the last hour winding past marsh and spruce that signal civilization’s fade. Floatplanes occasionally splash down at Rest Lake, but most arrivals still prefer the slow approach by two-lane blacktop, savoring every mile of encroaching quiet.