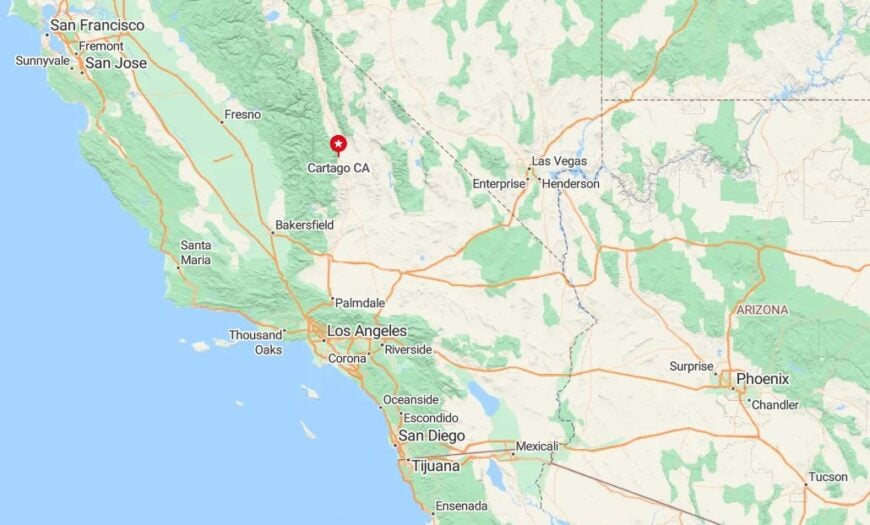

Would you like to save this?

There are towns that don’t try to be found—places that linger gently at the edge of things, where roads narrow, noise fades, and the land begins to speak instead. Eastern California is scattered with them, resting quietly between sunlit ranges, beneath cottonwood shade, or along the ghosted paths of old rail lines.

They feel rooted and calm, shaped more by the land than by time, and kept company by wind, sky, and memory. Life moves slower here, not out of nostalgia but because the pace has always fit just right.

For those who crave stillness or long to feel the rhythm of a quieter world, these towns aren’t just worth visiting—they’re worth remembering.

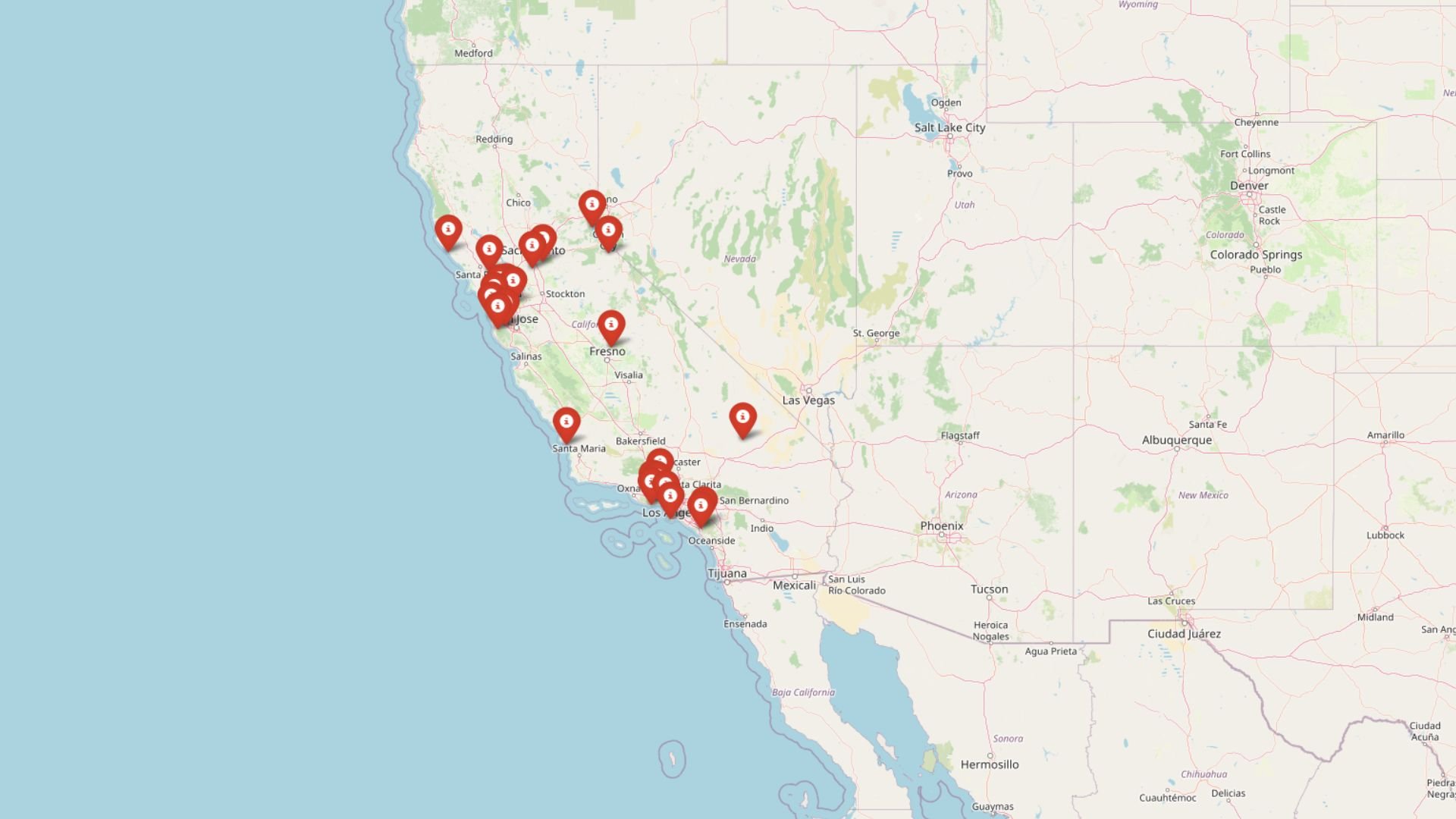

25. Benton – Mineral Springs and Ghost Echoes Near the Nevada Line

Old mining cabins and a 1940s bathhouse cluster at the base of the White Mountains where hot springs bubble up through sage. Benton’s handful of full-time residents tend rustic inns and shepherd visiting hikers looking for solitude and a deep soak.

Remnants of silver-era buildings give it a ghost town vibe, though the aroma of sulfur and creosote bush still says “lived-in.” Mornings bring silence broken only by magpies, and nights fall over empty fields still heated from below.

Most passersby miss the turnoff entirely, which suits locals just fine. The distant glow of Bishop never reaches these foothills, preserving pitch-dark skies and a timeless hush.

Where is Benton?

Benton lies on Highway 120 just west of the Nevada state line, where Inyo and Mono counties meet. The town sits at nearly 6,000 feet, with snowy peaks rising behind it and desert floor spreading eastward.

Drivers reach it from US 6, about 35 miles north of Bishop. Its location on a lightly traveled loop keeps traffic sparse and purposeful.

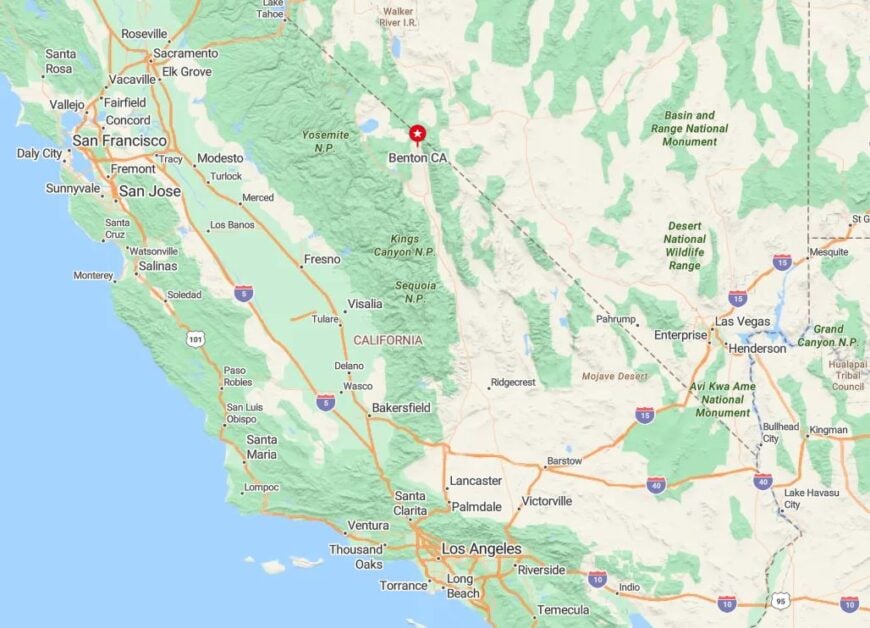

24. Chalfant Valley – Alpine Views from a Quiet Ranch Flat

Chalfant Valley is a narrow belt of ranch land lying beneath the shadow of the Sierra Crest, home to fewer than 700 people. Long fences stretch toward the White Mountains, and alfalfa fields shimmer in the midday heat.

There’s no gas station or café, only tidy homesteads, a volunteer firehouse, and the occasional tractor plodding down a side road. Mule deer graze near dry creek beds, and the silence is broken mostly by the whoosh of hawk wings.

With Bishop twenty minutes south, Chalfant acts as a fringe settlement for those who prefer wide spacing and dark skies. The eastern boundary dissolves into the Inyo National Forest, where the only movement comes from wind.

Where is Chalfant Valley?

Located along Chalfant Road just off US 6, this community marks the southern edge of Mono County. Though close to Bishop, it remains unincorporated and free of commercial trappings.

The valley’s low-slung homes blend with pasture and scrubland, giving the impression of a place half-wild, half-cultivated. Visitors usually pass it by en route to Nevada—unless they’re looking for space.

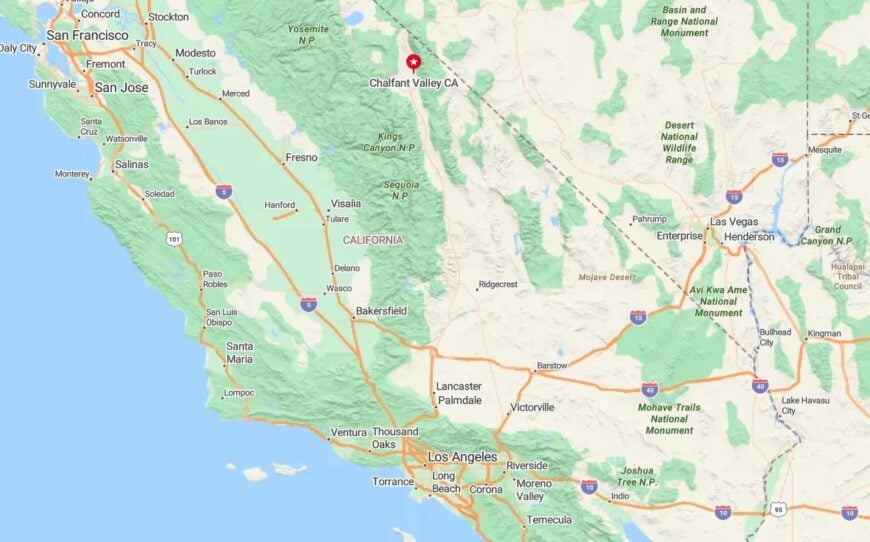

23. Cartago – Forgotten Stage Stop Beside a Salted Shore

On the western fringe of Owens Lake, Cartago’s weathered ruins and lonely ranch houses mark where stagecoaches once paused for water and rest. Today, the town’s stillness clings to remnants of stone foundations and mesquite windbreaks.

With a population that barely tops two dozen, there are no shops or stoplights—only distant views of the Sierra peaks and the empty lakebed glinting in the sun. Coyotes and jackrabbits outnumber people tenfold.

Time moves slowly here, as if waiting for the rail line that vanished a century ago. The hush is heavy, and the appeal lies in its ability to stay exactly as forgotten as it wants to be.

Where is Cartago?

Would you like to save this?

Just off US 395, Cartago sits a few miles north of Olancha on the edge of Owens Lake. Its old pump houses and crumbling walls line the highway but blink past in an instant if you’re not watching.

Flanked by the Sierra foothills and the lake’s white crust, it’s one of the last visible traces of the region’s stagecoach era. Few stop—but those who do often return for the silence.

22. Fish Lake Valley – Remote Basin Tucked Against the White Mountains

While technically across the state line in Nevada, Fish Lake Valley leans against the Eastern California boundary and shares its stark high-desert solitude. Alfalfa fields, dust roads, and a single general store mark this remote plain.

A scattering of mobile homes and working ranches hug the basin floor, with the massive face of the White Mountains rising just west. Travelers come seeking hot springs, solitude, and sunsets that seem to take hours to fade.

Most maps gloss over the place, and few signs point the way. That lack of invitation keeps the crowd thin and the stars bright.

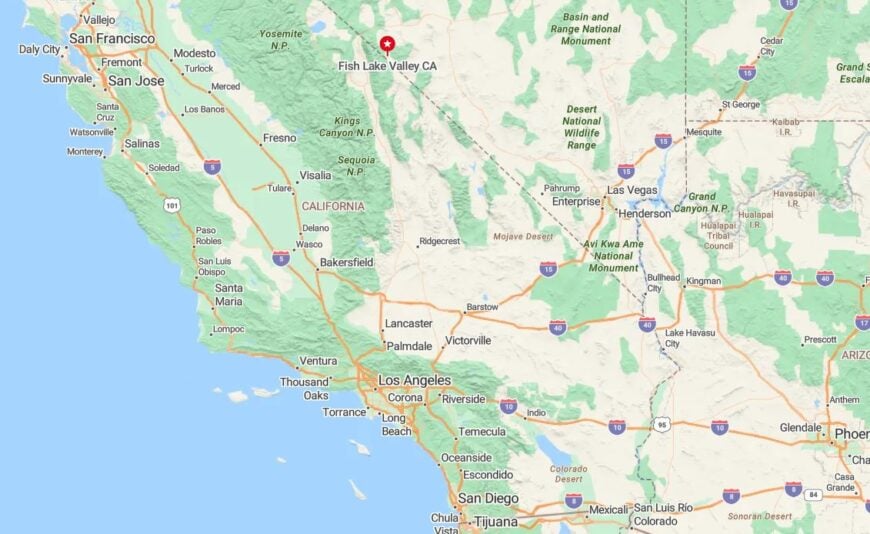

Where is Fish Lake Valley?

The valley sits just across the California-Nevada border, east of Deep Springs and south of Dyer. California drivers reach it via State Route 266, slipping through a pass that dips into the Great Basin.

Its relative inaccessibility and minimal development give it the same hush found just across the line in Inyo County. For many, it’s the last glimpse of Eastern California’s wilderness, stretched into Nevada.

21. Hammil Valley – A Strip of Green Hidden Between Dusty Ranges

Wedged between the towering Sierra and the White Mountains, Hammil Valley is a stitched quilt of ranches, irrigation ditches, and sloped barns. With only a few hundred residents, it moves to the rhythms of hay seasons and snowmelt.

Lone cottonwoods cast evening shadows across gravel roads, and irrigation wheels sit half-submerged in spring floodwater. Livestock outnumber tourists, and most outsiders see the place only from a windshield blur on US 6.

The isolation is more agricultural than arid—quiet not from abandonment but from continuity. It’s not forgotten, just not bothered.

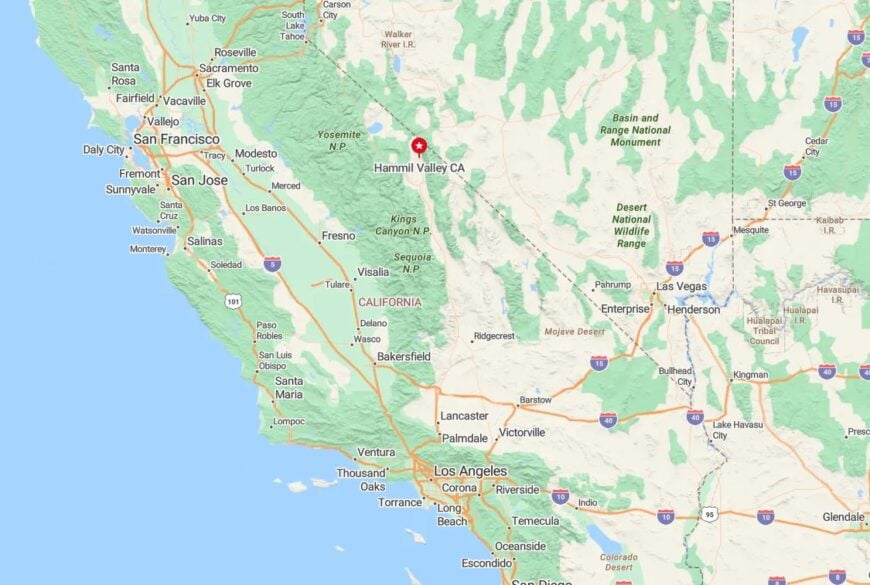

Where is Hammil Valley?

Hammil Valley lies along US 6 between Chalfant and Benton in Mono County. It rests in a deep trough formed by ancient glacial flows, with 13,000-foot peaks hemming it in on either side.

Access comes by car only, with no public transit and sparse signage. The location’s simplicity belies the beauty of its sunrise over white-capped ridges.

20. Mill Canyon – Forested Pocket High Above Mono Lake

Mill Canyon hides in the folds of the Bodie Hills, a green cut swaddled by lodgepole pine and the distant hush of mining ghosts. A few rustic cabins dot the meadows where deer graze, and the only sounds come from wind-rustled needles and the burble of spring-fed creeks.

Once a logging outpost for nearby Bodie, the canyon now plays host to seasonal anglers and those seeking shelter from both heat and crowds. No cell towers reach this far, and no businesses interrupt the hush.

Most find Mill Canyon only after turning off onto gravel, then gravel offshoots. It’s the kind of place where solitude greets you before your engine cools.

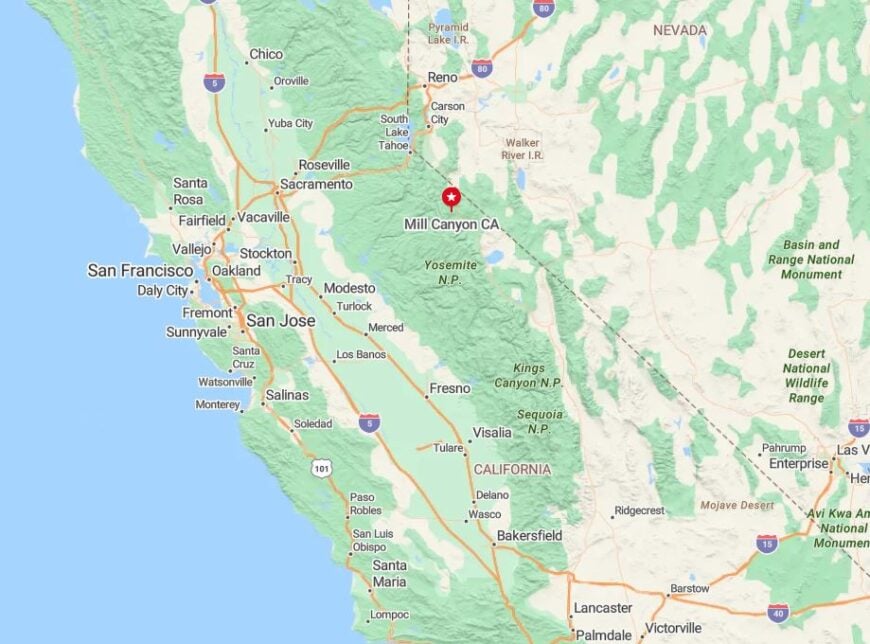

Where is Mill Canyon?

Mill Canyon lies northeast of Mono Lake, accessible by rugged backroads off Cottonwood Canyon or Bodie Road. It sits just west of the Nevada line but feels far removed from anywhere.

To reach it, travelers must leave pavement behind and commit to high-clearance roads. This inaccessibility helps the pine-ringed valley remain a locals-only secret.

19. Toms Place – Alpine Outpost with a Single Lodge

Toms Place clings to a bend in Rock Creek Canyon, where an old stone lodge has served weary travelers since 1917. Fewer than fifty residents live in the scattering of cabins and trailers tucked between ridges.

Fly-fishing, horseback trails, and wildflower hikes fill summer days, while winter buries the town under snow that muffles even the highway’s hum. The original lodge still dishes out coffee to hunters and hikers chasing silence.

With no gas station, grocery, or stoplight, it remains more trailhead than town—but those who linger know that’s the draw.

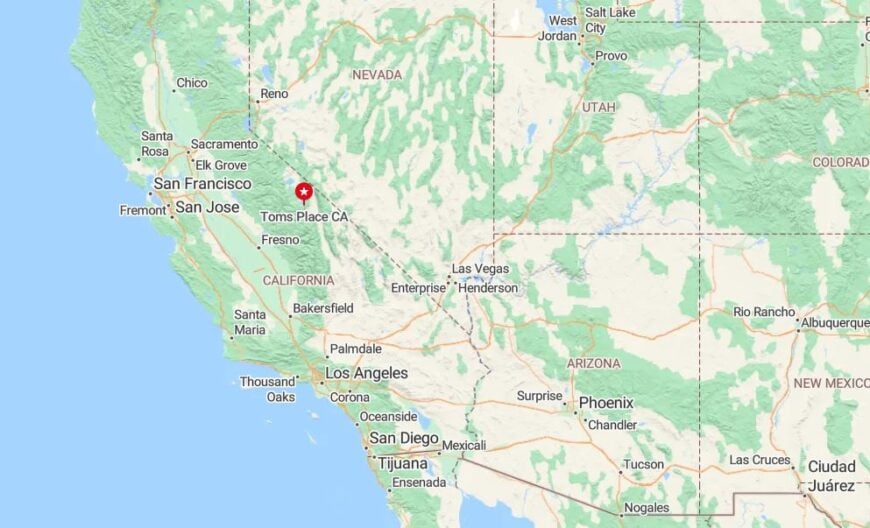

Where is Toms Place?

The settlement lies off US 395 in southern Mono County, just fifteen miles north of Bishop. Perched at 7,000 feet, it sits at the mouth of Rock Creek Canyon, which climbs into the Sierra backcountry.

Visitors often blink and miss it unless they’re turning west into the mountains. Once there, the granite peaks and glacier lakes make it clear why this dot on the map endures.

18. Little Lake – Stone Foundations in a Lava-Strewn Basin

Little Lake is more memory than town now, with just a few buildings and a namesake lake that gleams beside lava ridges. Once a rail stop and rest point for travelers on US 395, today it whispers through ruins and cracked blacktop.

Abandoned motels, dusty trails, and petroglyph sites surround the basin, which is rich in history but devoid of commotion. Coyotes cross the road at dusk, and the basalt cliffs hold onto heat long after sundown.

Even with the highway nearby, Little Lake feels wrapped in stillness—like a fossil in plain view.

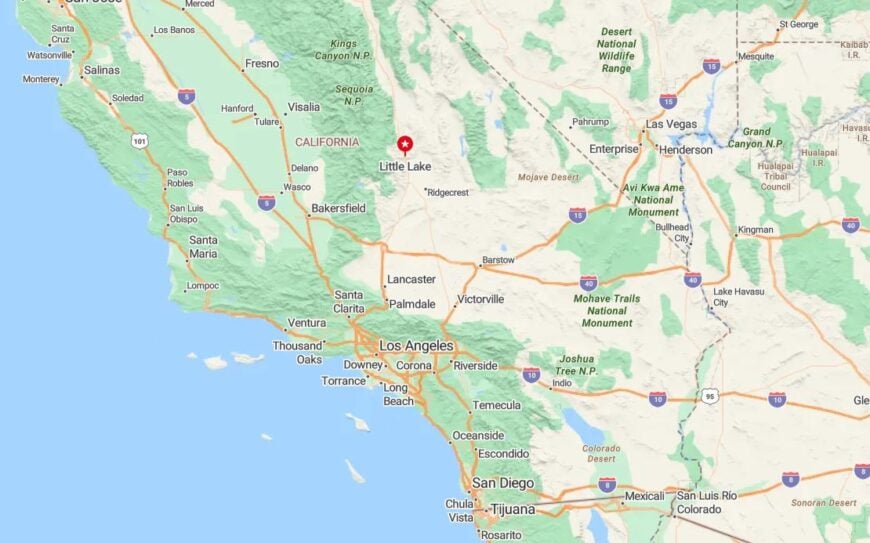

Where is Little Lake?

Little Lake sits near the southern end of Inyo County, just north of the Kern County line. US 395 threads past its edge, but no services mark the stop.

The turnoff leads to a boat launch and an overlook of the spring-fed lake and surrounding lava beds. Remote and bypassed, it’s a final southern breath of Eastern California’s forgotten corners.

17. Round Valley – Where Granite Walls Meet Pastureland

Round Valley lies just northwest of Bishop, in a bowl-shaped basin rimmed by the Sierra on one side and the White Mountains on the other. Home to ranchers, artists, and backcountry skiers, it hides in plain sight off the main highway.

With no commercial core and only one store, life moves to the rhythms of snowfall, hay harvests, and the changing light on granite cliffs. Residents prize the quiet so much that new builds are rare and often off-grid.

Round Valley feels like a pause button between town and wild—protected, still, and neighborly in the way of places that know their edges.

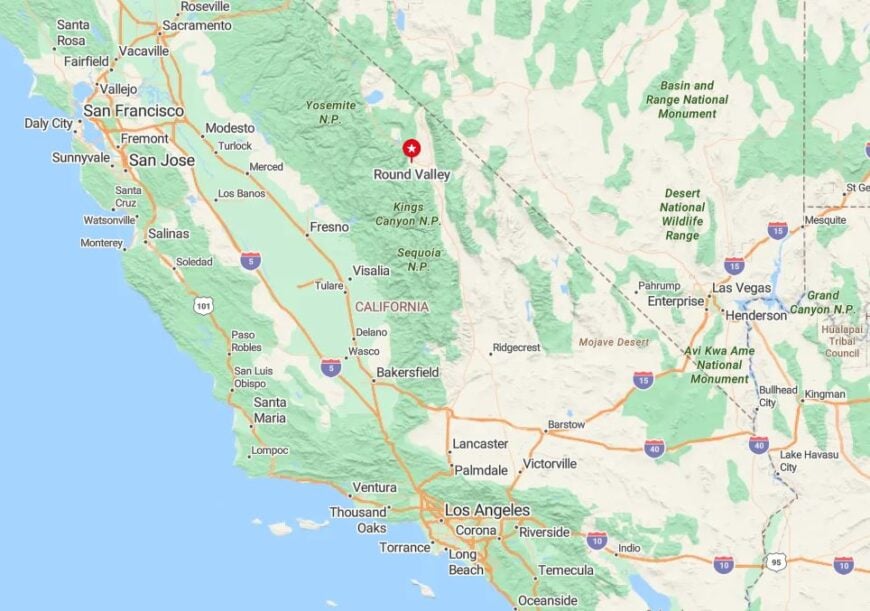

Where is Round Valley?

Located a few miles west of US 395, Round Valley rests at 5,000 feet where pine forest gives way to pasture. Access comes via Round Valley Road from Bishop or Paradise.

Because it hugs the base of the Sierra, the community sees dramatic sunsets and cool night breezes. The lack of signage or major development keeps it off itineraries and under the radar.

16. Pine Creek – Canyon Camp with Mining Roots and Alpine Vistas

Would you like to save this?

Pine Creek traces the old path of a tungsten mine that once fed war efforts and kept a canyon town alive. Today, its relics and bunkhouses sit quiet under steep granite cliffs carved by Ice Age glaciers.

Only a few permanent residents remain, living near the creek’s roar and the silence of shuttered shafts. Trailheads lead deep into John Muir Wilderness, and mule deer often outnumber hikers even in summer.

The town’s end came with the mine’s closure, but its peace endured—and it’s become a haven for those chasing vertical stone and velvet skies.

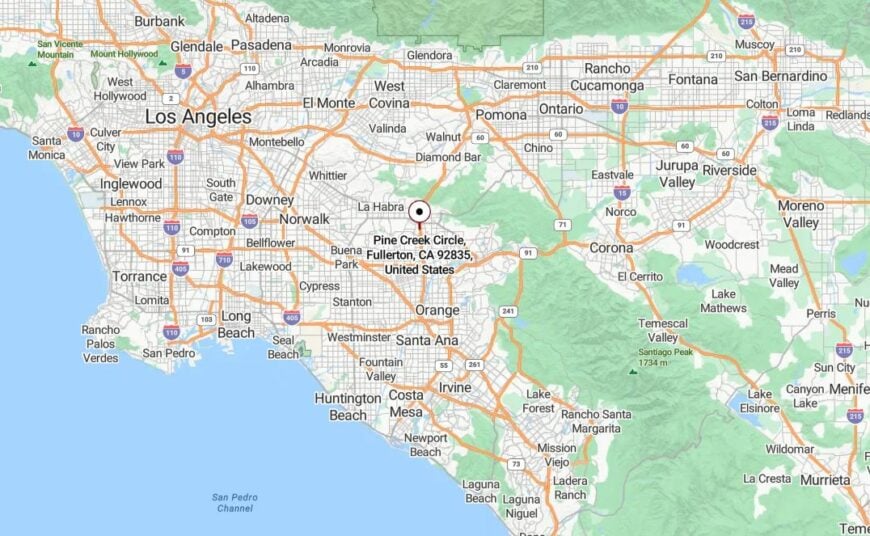

Where is Pine Creek?

Pine Creek lies west of Bishop in Inyo County, at the terminus of Pine Creek Road. It’s a steep, winding route that climbs into the high canyon and ends where the pavement does.

The area is known to climbers and wilderness hikers but is off most tourist routes. Its tucked-in setting means few stumble upon it by chance.

15. Walker – River-Bent Hamlet Ringed by Granite

Tucked into the Antelope Valley, Walker hums softly beside the West Walker River, with meadows to one side and granite knobs to the other. About 600 people call it home, most centered around a general store, a café, and a handful of motels.

Fishing, RV camping, and hiking the Pacific Crest Trail nearby keep summer lively, but winters blanket the town in hush. It’s a place where porch lights glow against the snow and the river never quite stops its whisper.

The town is too small to be hurried and too remote to be crowded—making it a perfect pause on the long highway north.

Where is Walker?

Walker is located in northern Mono County, on US 395 near the Nevada border. It’s one of the last Eastern Sierra stops before crossing into Douglas County, Nevada.

Surrounded by Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, it’s both accessible and remote. The scenic byway in either direction frames Walker like a hidden fold in the mountain quilt.

14. Mono City – One-Street Town Above the Lake’s North Shore

Just a few dozen homes perch on the hill above Mono Lake’s quiet northern shore. Mono City has no shops, no gas, and no real traffic—only long views over water and salt towers that look sculpted by another planet.

The town began as housing for highway workers and never grew much larger. Its isolation feels intentional, and its appeal lies in its view: Mono Lake at dusk, when the sun turns the alkali water lavender.

Even nearby Lee Vining feels bustling by comparison. Here, it’s just you, the lake, and the sky.

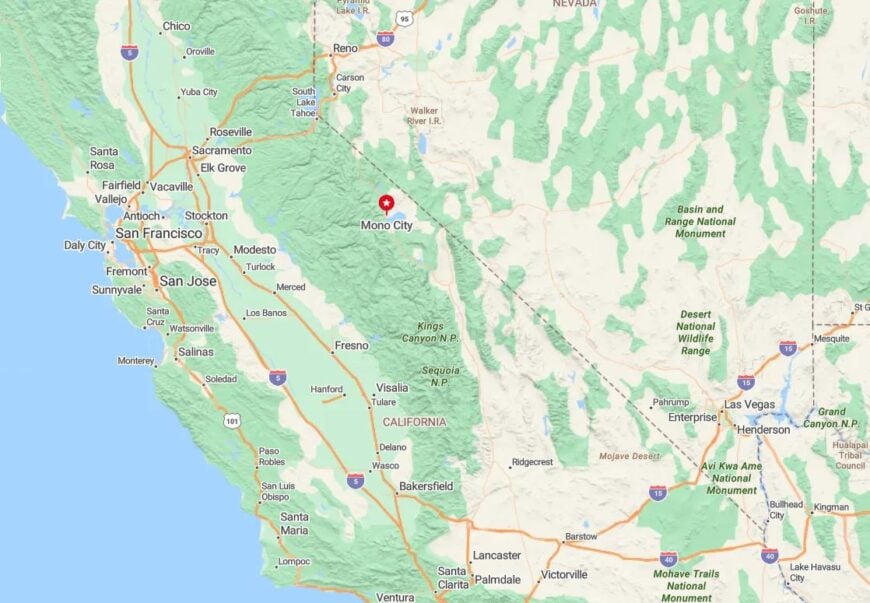

Where is Mono City?

Mono City lies just north of Mono Lake along California 167. A single paved road winds up from US 395 and then fades to gravel as it climbs northeast toward the Nevada line.

There are no services, so visitors bring what they need and leave what they don’t. It’s one of the quietest communities in Mono County.

13. Tinemaha – Faint Traces Beside the Reservoir

Tinemaha is more concept than town now—a string of ranch sites and irrigation works near the Inyo Mountains, set beside the Tinemaha Reservoir. Only a few residents remain, tucked behind tamarisk groves and cottonwood shade.

Fishermen cast lines from shore, and hawks glide over the flatlands with barely a sound. The wind is often the loudest thing for miles.

The town never incorporated, never built out, and never invited attention. Its draw is stillness in a land mostly shaped by water and dust.

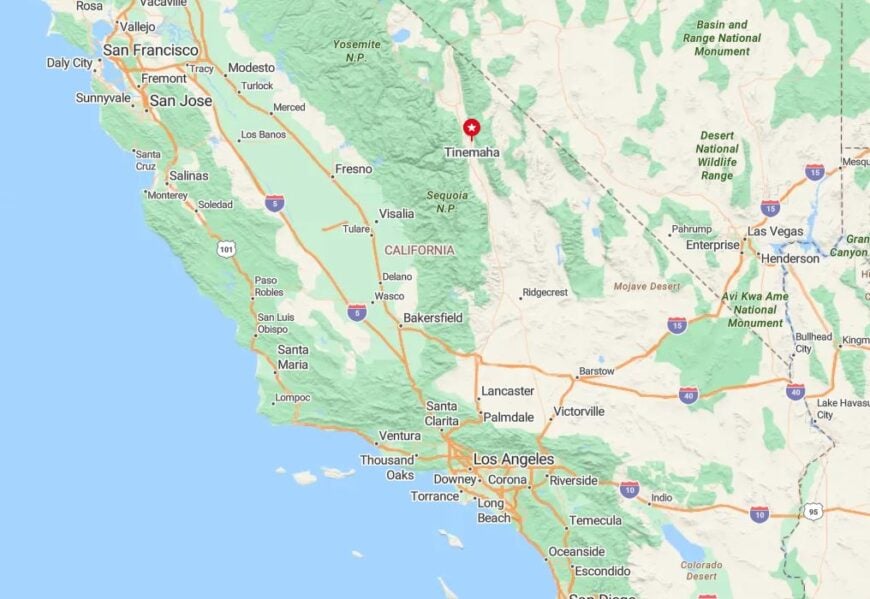

Where is Tinemaha?

Tinemaha sits twenty miles south of Big Pine along US 395, just east of the Sierra Crest and near the Owens River. The reservoir itself is the clearest landmark—a long blue basin surrounded by beige scrub.

Turnouts lead to the water’s edge, but signs are minimal. That absence of markers adds to the feeling of finding something hidden.

12. Fort Independence – Tribal Hamlet on the Valley Floor

Fort Independence is a small tribal community home to the Paiute people, set beneath wide Owens Valley skies. A tribal office, community center, and casino form its center, but the rest is open land and big mountains.

The rhythm of life is slow and purposeful. The town’s modest footprint blends into the terrain, and respect for the land is evident in its preserved quiet.

Visitors often pass without realizing it’s there, which suits the place just fine.

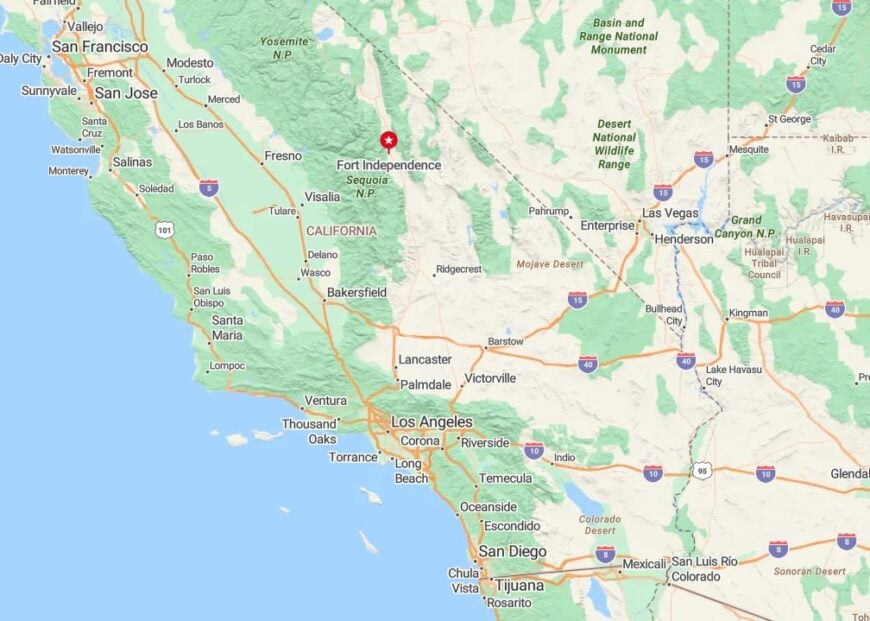

Where is Fort Independence?

The community is located along US 395 in Inyo County, just north of Independence. Bounded by the Inyo Mountains to the east and the Sierra to the west, it lies along one of the quietest stretches of Owens Valley.

It’s not a tourist destination, but those who stop find cultural history and calm—a reminder that the land has long been home.

11. Sunland – A Backroad Hamlet Outside of Bishop

Sunland hugs the edge of Bishop’s shadow, a quiet residential grid spread across ranch plots and cottonwoods. Horses graze near dirt lanes, and quail dart through lavender bush near mailbox posts.

Though technically close to town, Sunland feels rural and tucked away, accessed by backroads that discourage casual discovery. There’s no main street, just a loose net of driveways and gravel.

Its charm lies in its slow pace and closeness to the wild—one step removed from the bustle of Bishop, yet fully part of the Eastern Sierra’s rhythm.

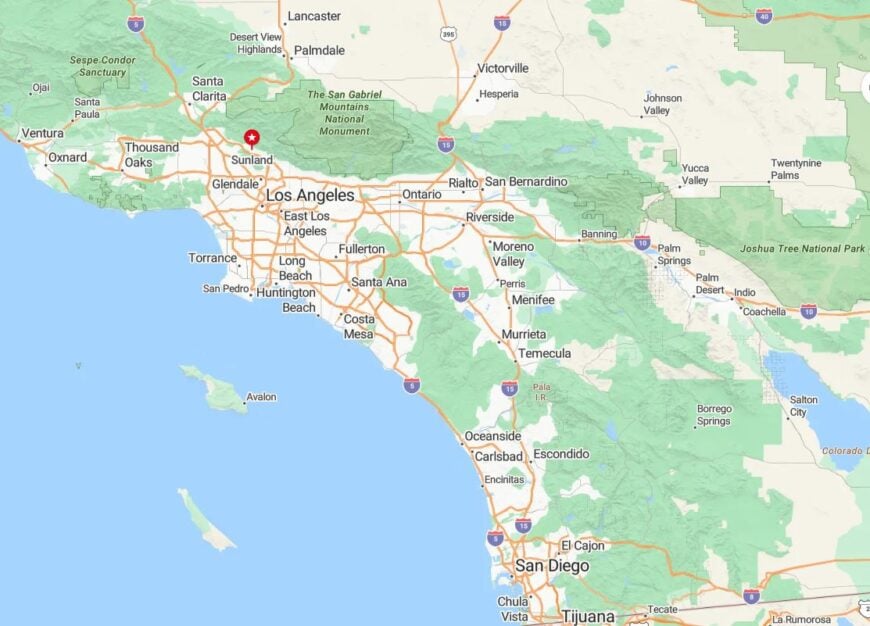

Where is Sunland?

Sunland sits a few miles southeast of Bishop in Inyo County, tucked between the Owens River and the foothills of the White Mountains. Access is from Sunland Drive or Warm Springs Road, each one-lane and largely unsigned.

It’s a residential pocket that flies under the radar, free of signage and commercial buildup. Locals know it, but visitors rarely do.

10. Darwin – An Almost-Forgotten Mining Hamlet Off Highway 190

Roughly thirty-five people keep watch over Darwin’s weather-worn shacks and clapboard storefronts. Visitors poke around rusty stamp mills, photograph bottle-lined fences, and hunt for petroglyphs in nearby canyons while lizards own the soundscape.

Mining once fed every wallet here, and a few artists now use abandoned bunkhouses as studios, though there is no store, gas, or reliable phone signal. Today, the town’s hush is preserved by a dead-end spur road that slips behind rocky hills, leaving it invisible from the highway.

Wind slides through empty streets, and midnight stargazing often means not a single headlight for hours. The combination of history, art, and pure desert stillness gives Darwin its off-grid allure.

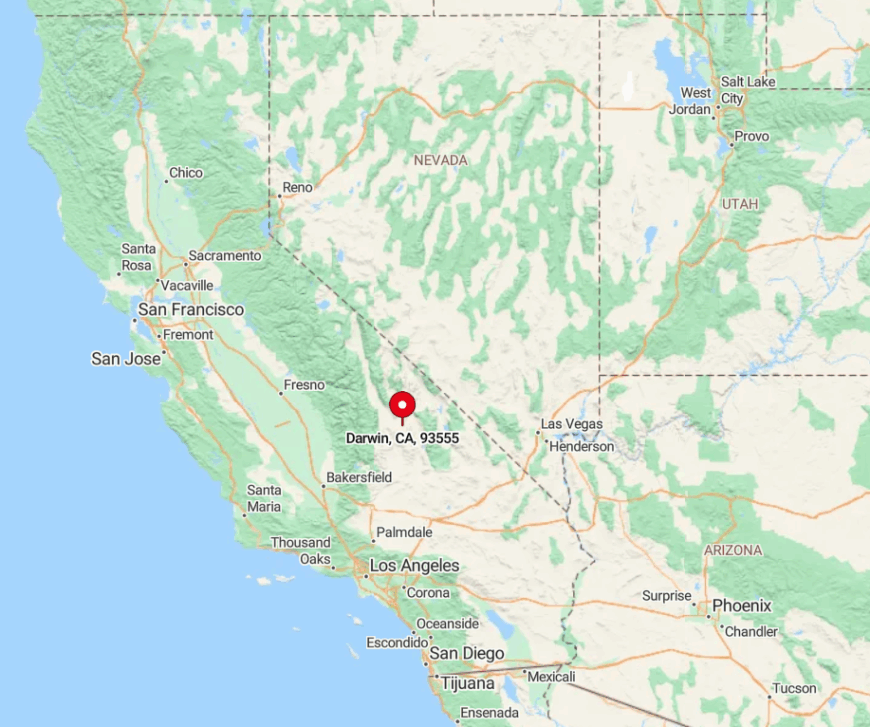

Where is Darwin?

The hamlet sits in Inyo County, fifteen miles west of the boundary of Death Valley National Park. Shielding ridges on every side and the absence of through-traffic keep it secluded, even though Highway 190 passes only seven miles away.

Reaching town requires turning south onto Darwin Road and following a cracked ribbon of pavement until the pavement ends at the old post office. That one deliberate turn filters out casual motorists, leaving the settlement to those who truly seek it.

9. Deep Springs Valley – Home to Cattle, Scholars, and Little Else

Fewer than forty residents, most of them students and staff of two-year Deep Springs College, share a million-acre view in this high desert basin. Days revolve around tending cattle for the college ranch, roaming sagebrush flats on horseback, and scaling the White Mountains for bristlecone pines older than the pyramids.

Education and ranching stand as the sole industries, entwined in a curriculum that balances Plato with branding irons. The nearest public settlement is forty miles away, and mail arrives only three times a week.

With no commercial center, streetlights, or cell towers, the valley slips easily into velvet darkness each evening. The stark openness, punctuated only by low stone dorms and grazing steers, defines its deep solitude.

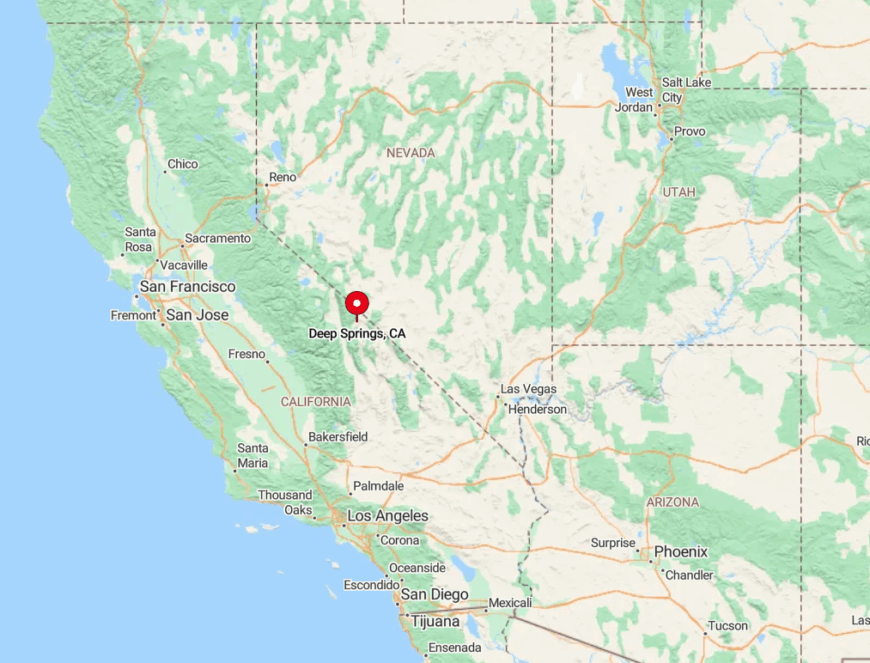

Where is Deep Springs Valley?

The valley lies east of the White Mountains on State Route 168, about thirty miles from the junction with US 395 at Big Pine. Westgard Pass tops 7,300 feet, and winter storms can block the road for days, heightening the region’s isolation.

A single paved lane threads across the flats, then dead-ends at the Nevada line, so motorists rarely pass unless Deep Springs is their goal. Supplies usually come from Bishop, an hour away, emphasizing how far the basin sits from the daily bustle.

8. Keeler – Wind-Whipped Ghost Port on the Shores of a Vanished Lake

Some sixty residents hunker in trailers and century-old cabins along the skeletal shoreline of Owens Lake. Photographers wander past abandoned rail cars, a crumbling depot, and wooden pilings that once welcomed steamships before water diversions turned waves into salt crust.

A hint of soda ash processing persists, but the rail whistles fell silent generations ago, leaving only hobby prospectors and curious travelers. Fierce afternoon winds whip gypsum dust across town, and the nearest grocery cart is twenty-five miles away in Lone Pine.

Keeler’s emptiness is sharpened by the flat white playa that stretches toward the Inyo Mountains like an inland sea gone missing. The mood is part lunar, part Western, entirely removed from modern convenience.

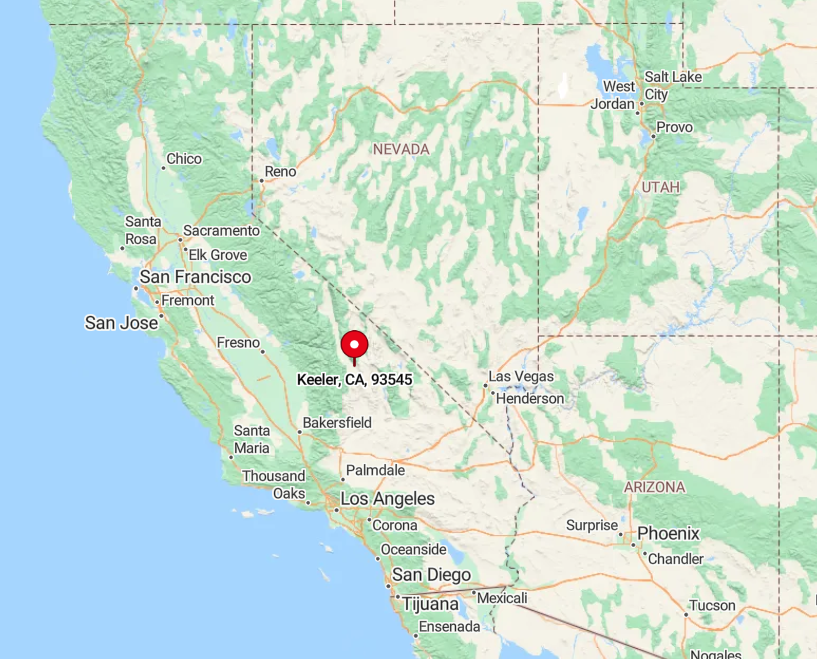

Where is Keeler?

The settlement sits on California 136, hugging the east edge of Owens Lake in Inyo County. Salt flats on one side and a steep range on the other funnel traffic past without a reason to linger, enhancing the sense of abandonment.

Drivers reach it by leaving US 395 south of Lone Pine and following the lonely spur that skirts the dry lake bed. With no public transit and sparse services, visitors plan fuel and water before arrival.

7. Panamint Springs – One Outpost Between Mountains and Death Valley

A population of just over a dozen operates a combined motel, café, and gas pump that amounts to the whole of Panamint Springs. Guests hike to Darwin Falls, scramble over Panamint Dunes, and test night-sky photography while coyotes sing backup.

The family business is effectively the town’s sole industry, aside from highway maintenance crews that appear only in emergencies. Sheer cliffs of the Panamint Range rise to the east, and an ocean of gravel flats spreads west, leaving fifty vacant miles in either direction.

At twilight, porch lights merge with stars because no neighboring glow competes. The comfort of having lodging yet no settlement nearby gives the outpost its rare balance of access and solitude.

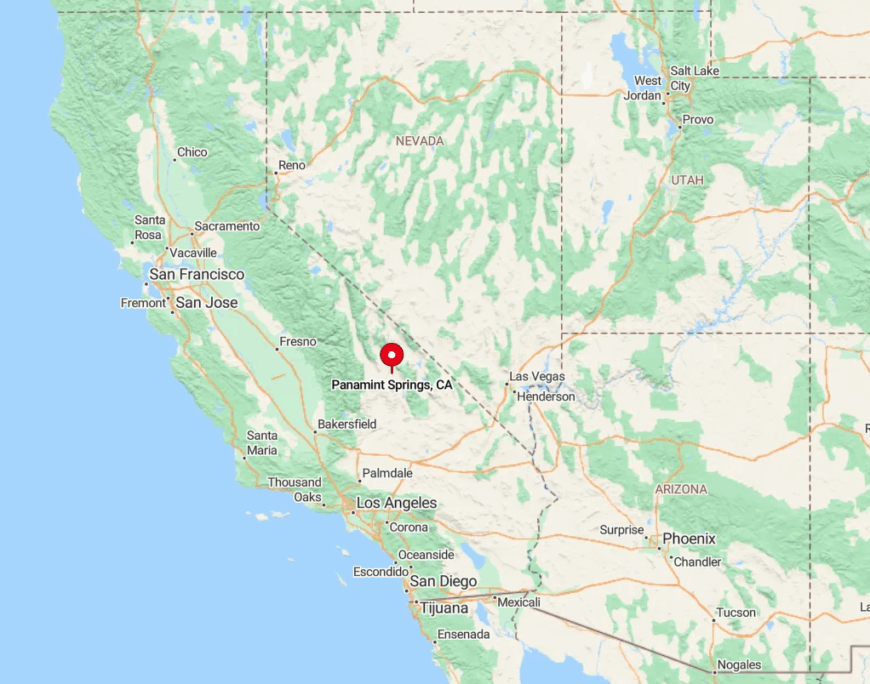

Where is Panamint Springs?

Located along California 190 on the western margin of Death Valley National Park, the stop anchors a remote stretch between Lone Pine and Furnace Creek. Towne Pass climbs above 4,900 feet just east of town, and summer temperatures on the descent can top 120°F, discouraging casual drop-ins.

Those coming from the south meet similar emptiness across Panamint Valley before the single set of buildings appears. Fuel is the first and last for almost ninety miles, underscoring how isolated the spot truly is.

6. Shoshone – Adobe Outcropping at the Southern Gate to Death Valley

About thirty locals reside among adobe storefronts, date palms, and a historic gas station that has served desert wanderers since 1925. Visitors explore Dublin Gulch’s hand-carved cave homes, bird-watch at a spring-fed wetland, and admire glowing lava buttes at sunset.

Hospitality and modest farming of Medjool dates form the village’s economic spine, supported by a small museum recounting miner lore. Empty volcanic mesas surround every roadway, and after dusk, traffic thins until only crickets and the occasional wandering burro remain.

With nearest neighbors over thirty miles away, Shoshone keeps its frontier aura intact. The stillness is punctuated only by passing travelers refilling water before pressing into Death Valley.

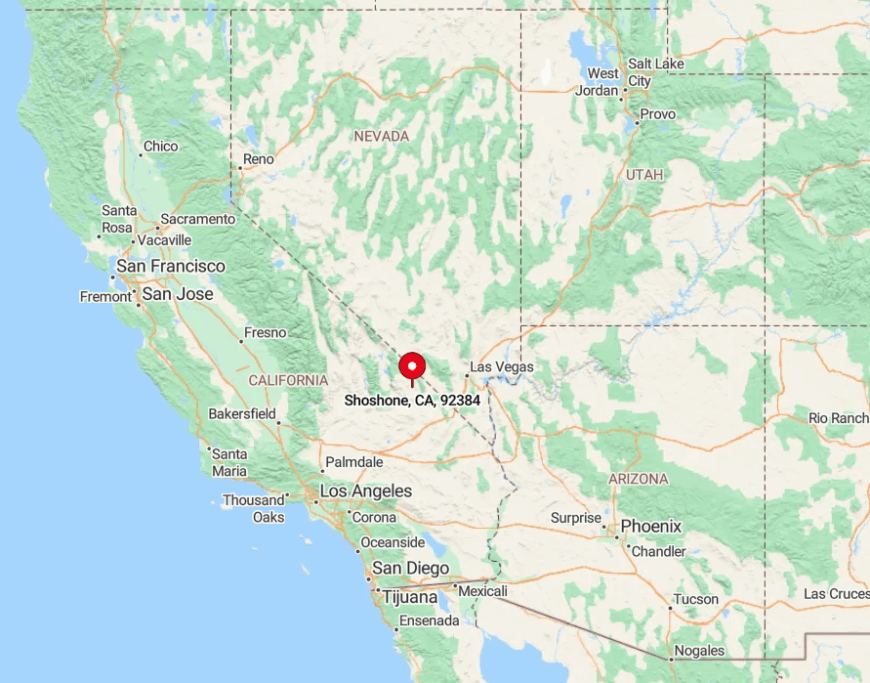

Where is Shoshone?

The town rests at the junction of California 127 and California 178, just inside Inyo County and fifteen minutes from the Nevada border. Surrounded by public desert lands, it avoids suburban creep from Las Vegas, ninety miles to the east.

Access comes via long two-lane highways that crest barren passes, limiting approach to private vehicles and the occasional tour bus. Once the sun sets, the distant glow of Vegas barely grazes the horizon, preserving clear desert skies.

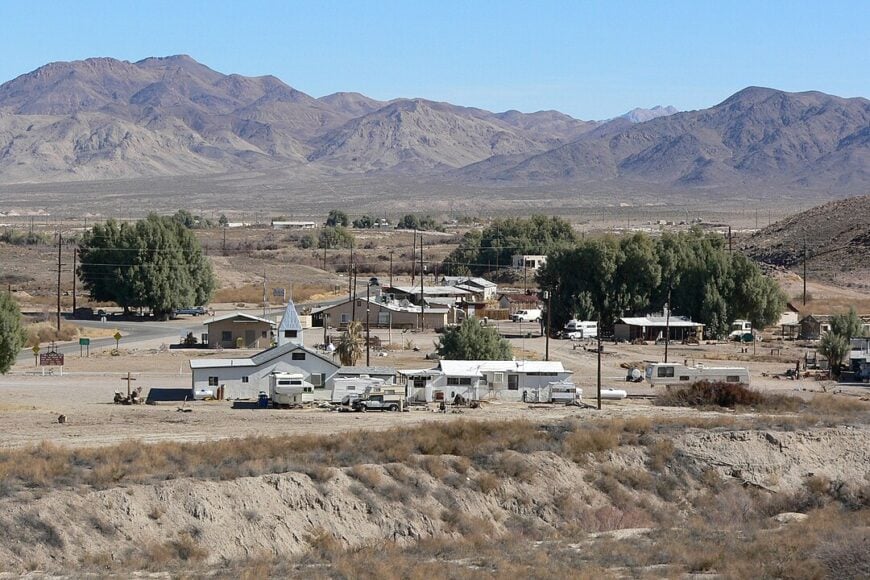

5. Tecopa – Hot Springs Hideaway Amid Badlands and Borax History

Roughly 150 people live amid steaming pools, hand-built bathhouses, and mud hills that shift from beige to rose in late light. Days are filled with soaking in public concrete tubs, tasting date shakes at China Ranch, and walking the Amargosa River canyon where pupfish sparkle in shallow water.

Bathhouse caretaking and small-scale agriculture supply most jobs, while a few artists sell ceramics shaped by local clay. Streetlights never arrived, so the Milky Way regularly steals the show once the pools empty.

Hoof-print dirt roads, patchy cell service, and vast badlands to every horizon enforce the sense of being far from any grid. Those who linger describe a calm that settles over the village once the last day-tripper heads back toward Vegas.

Where is Tecopa?

Tecopa sits five miles south of Shoshone, reached by turning off California 127 onto Old Spanish Trail Highway. The loop road dead-ends in dramatic gullies, ensuring traffic is minimal and purposeful.

Las Vegas lies eighty miles east, and the closest supermarket is across state lines in Pahrump. Most arrivals drive themselves, though occasional cyclists brave the empty asphalt for an otherworldly approach.

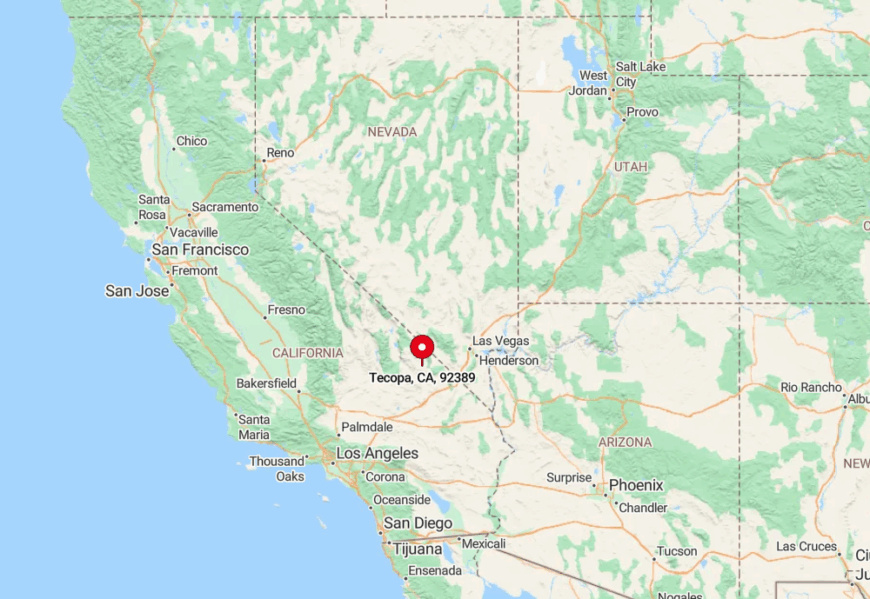

4. Olancha – Lone Cottonwoods Beside the Sierra’s Shadow

About 200 residents spread across broad ranch lots shaded by cottonwoods where the Sierra Nevada meets the Owens Lake playa. Outdoor lovers climb Owens Peak, watch geyser eruptions at nearby Crystal Geyser, and buy peppered buffalo jerky at a roadside stand that has become a cult favorite.

Ranching, artisan jerky sales, and a modest motel-café pair with highway service jobs to keep the town humming. Granite walls to the west and a dry lake to the east leave Olancha with unbroken views and few neighbors.

Even with US 395 running through it, long gaps between fuel stops north and south filter out heavy crowds. Evening silence often settles while pink alpenglow paints Mount Whitney far to the north.

Where is Olancha?

The community sits twenty miles south of Lone Pine on US 395 in southern Owens Valley. With no alternate routes and sparse public transit, the settlement relies on personal vehicles for every supply.

Desert stretches of thirty miles separate it from the next clusters of lights, accentuating its remote feel. Drivers heading north notice the sudden line of cottonwoods, refuel, and find the quiet contagious.

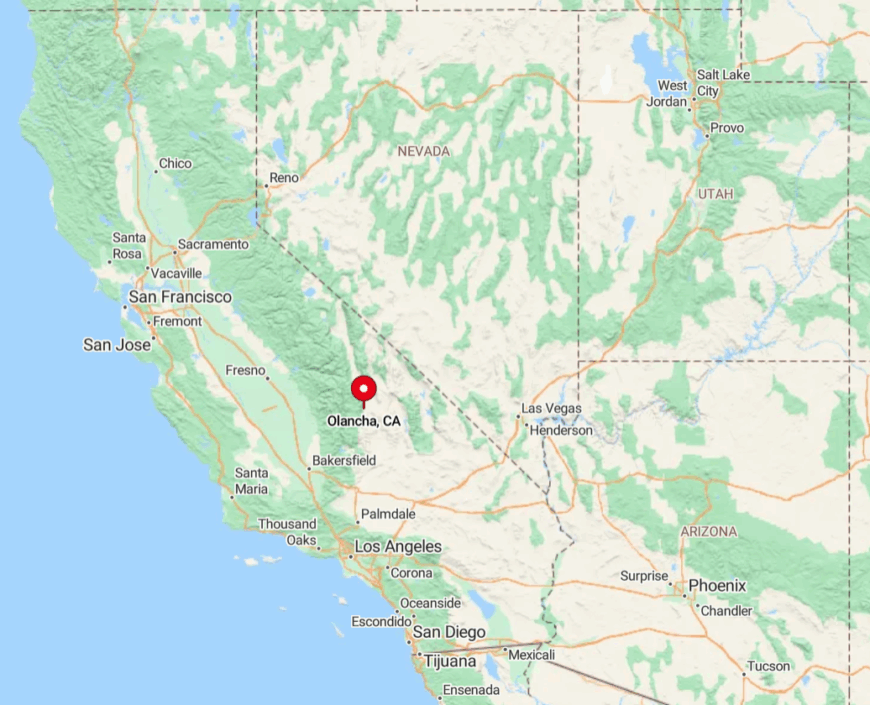

3. Lee Vining – Tiny Gateway Guarding Mono Lake’s Tufa Towers

Only 222 people reside beneath sheer cliffs where the Sierra’s east wall drops to the eerie waters of Mono Lake. Kayaks glide among limestone tufa spires, hikers venture into nearby Lundy Canyon for hidden waterfalls, and diners seek out the gas-station-turned-bistro serving buffalo meatloaf and famous fish tacos.

Tourism dominates the summer economy, supplemented by seasonal forestry crews and highway maintenance. Once Tioga Pass closes with the first big snow, traffic dwindles to a trickle, and many businesses shutter until spring.

The town’s one-street grid hugs cliffs on one side and alkaline water on the other, giving it nowhere to spread. Winter’s quiet, sealed by deep snowdrifts, grants Lee Vining an almost private claim on Mono Basin.

Where is Lee Vining?

The village sits at the intersection of US 395 and California 120 in Mono County, 120 miles south of Reno. When Tioga Pass closes, the only way in or out follows US 395, lengthening drives to Yosemite by over four hours and reinforcing isolation.

Bus service is seasonal, so personal vehicles remain the chief method of arrival. The abrupt drop from 10,000-foot peaks to the lake shore makes the approach as dramatic as the destination.

2. Bridgeport – High-Desert County Seat Ringed by Alpine Meadows

Fewer than 600 residents center their days around a brick 1880s courthouse, expansive cattle pastures, and storefronts that feel lifted from a Clint Eastwood set. Anglers test Bridgeport Reservoir for trout, hikers tread the Hoover Wilderness, and bathers soak in Travertine Hot Springs with Sawtooth Ridge soaring above.

Government jobs, ranching, and boutique tourism share the economic load, with a smattering of outfitters guiding climbers and hunters. Winter storms can close both Sonora Pass and Conway Summit, isolating the valley for days and muting the highway rumble.

Even in July, the wide main street rarely sees a crowd larger than a local parade. Open rangeland on every compass point cements the sense of elbow room.

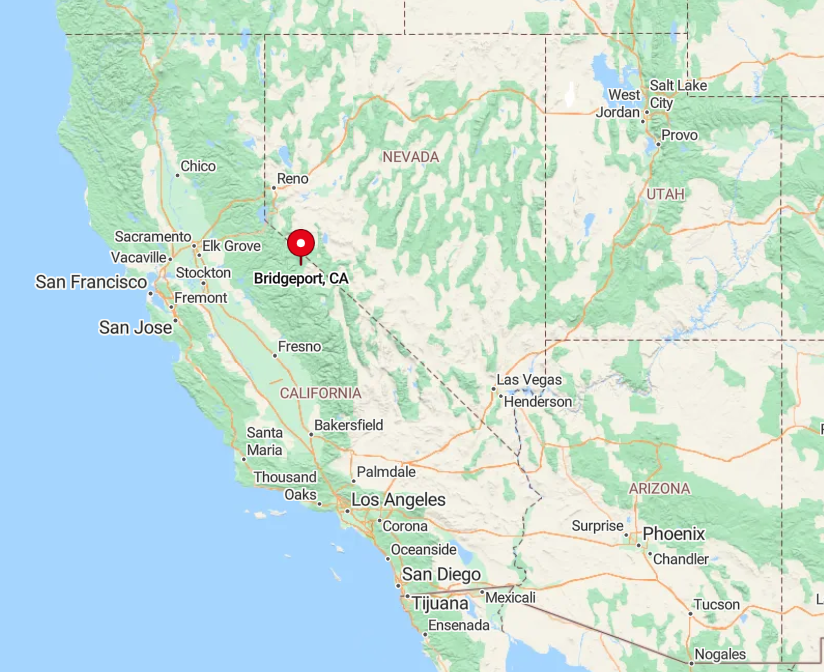

Where is Bridgeport?

Bridgeport lies along US 395 in northern Mono County, roughly 80 miles north of Bishop and 20 miles south of the Nevada line. Mountain passes on either side can shut down under heavy snow, forcing long detours and reinforcing the town’s self-reliance.

Public transport is limited to an infrequent county shuttle, so visitors generally arrive by car or motorcycle. The high valley setting at nearly 6,500 feet adds a pleasant crispness to summer nights that rewards the drive.

1. June Lake – Four Sapphire Lakes in a Hidden Glacial Cirque

About 600 residents inhabit cabins and lodges that ring four glassy lakes tucked into a horseshoe-shaped canyon off US 395. Days pass with boating on Gull Lake, spotting aspen gold on the Parker Lake Trail, and carving powder at June Mountain Ski Area, where lift lines are often nonexistent.

Recreation tourism supports most livelihoods, complemented by small guiding outfits and seasonal art fairs. Granite walls tower overhead, and the loop road dead-ends within the cirque, keeping the area free of through-traffic and preserving a peaceful lakeside hush.

Nightfall reveals cabin lights twinkling like low stars against the cliffs, and a late paddle can feel wholly private. The balance of alpine scenery and limited access marks June Lake as the quiet crown of Eastern Sierra resort towns.

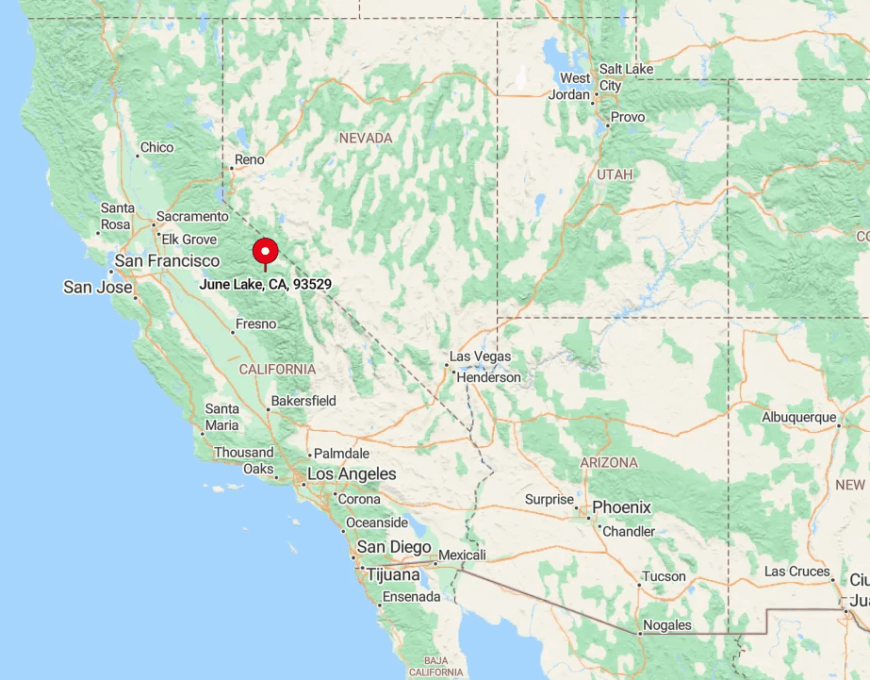

Where is June Lake?

The village sits twenty minutes north of Mammoth Lakes in Mono County, accessible by taking California 158 off US 395 to form the scenic June Lake Loop. Heavy snow sometimes closes the northern entrance, leaving a single way in or out and enhancing the sense of enclosure.

No scheduled bus reaches the canyon once winter sets in, so residents and guests rely on four-wheel-drive vehicles. Despite the nearby highway, the glacial basin’s granite walls buffer sound and create a tucked-away haven that feels far removed from city clamor.